This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Above: Nisha Kavalam speaks at the University of Utah about rape culture and being sexually assaulted.

Shock and self-hatred consumed the then-University of Utah student: How could something like this happen?

"I blamed myself a lot in the beginning," said Kavalam, who was attacked near the U. campus by an acquaintance.

In her state of trauma, however, Kavalam called upon her training as a victim advocate to guide her next step: reach out to resources and allies.

She ended up going to the college's Title IX office, which oversees a federal law barring sex discrimination at schools that receive funds from the U.S. government. It would take more than a year for the school to find her perpetrator responsible, a time line that prompted her to lodge a federal complaint Wednesday against the university, alleging it had violated federal law.

The 22-year-old Kavalam, who graduated in December with a degree in social work, said she first reported the assault a few weeks after she was raped by a fellow student in February 2015. The university's Title IX investigator decided in April 2015 there was not enough evidence to support her claim, she said. So, Kavalam appealed to a disciplinary panel of a half-dozen U. faculty, staff and students.

Nine months later — in January — that panel decided it was more likely than not that the male student had sexually assaulted her, she said.

Both Kavalam and the man she accused, she notes in her complaint, graduated before the disposition, finalized earlier this year when the university sustained the disciplinary panel's decision after an appeal from the accused student.

The Salt Lake Tribune generally does not name sexual assault victims, but Kavalam agreed to be identified.

Penny Venetis, executive vice president and legal director for Legal Momentum, a New York-based legal advocacy group for women, said nine months is a long time frame for an appeals process.

"Nine months of living on campus with someone who sexually assaulted you is a long time," she said, adding that other students on campus could be put in danger with an appeals process that lengthy.

The U.S. Department of Education recommends schools complete their investigation within 60 days, but it's not a requirement. That time frame does not include the appeals process, but department documents state that an "unduly long appeals process may impact whether the school's response was prompt and equitable as required by Title IX."

The U. investigates any allegations of discrimination, including sexual violence, but also must ensure due process for everyone involved, said Lori McDonald, the U.'s dean of students.

"We are heartsick to learn that any student felt the process was difficult," McDonald said, adding that administrators will continue to review procedures to make them more efficient and effective.

While investigations and hearings are pending, McDonald said, the school puts protective measures in place for students who report an assault. Student privacy law prevented her from speaking to specific disciplinary cases, she said.

From 2010 to 2015, the U. reported that it disciplined nine male students for sexual assault or sexual battery. Sanctions ranged from written reprimands to expulsion. One student received a written reprimand and agreed to a no-contact arrangement, four students were suspended, three others given probation, and one student was expelled from the school.

Kavalam would not discuss the sanctions imposed in her case. But, she said, she was "disappointed" and "did not feel a sense of justice from them."

Kavalam said she received effective counseling and help with classes through victim advocates, but had to prod administrators to convene the disciplinary panel to review her appeal, she said.

"Ultimately, what it came down to is if someone came up to me and said they were assaulted, I would encourage them not to report" to Title IX, Kavalam said.

Kavalam said she chose not to report the assault to police because she believed the school could hold the student accountable. She also was unsure of what to expect from reporting to law enforcement.

"I was in a very fragile place and I felt comfortable and safe reporting to the U.," she said.

A university's Title IX investigation is separate from a law enforcement investigation, though they may overlap.

Many women choose not to report to police, said Alana Kindness, executive director for the Utah Coalition Against Sexual Assault, but it does not make their claims less valid or trustworthy.

"By not believing victims and by questioning their credibility when they come forward, we are enabling offenders because offenders count on that," Kindness said. "We can count on society, law enforcement, family, the community and the courts dismissing a victim and questioning everything about their motives and their behavior. It just perpetuates the cycle."

Kavalam hopes her complaint will provoke the U. to speed future investigations and make other changes to ease the burden on students who report sexual assaults.

Currently, 181 institutions across the country are under investigation for violating Title IX, according to the Utah Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Westminster College currently is being probed by federal investigators for its handling of a 2013 sexual assault allegation.

A federal complaint also has been filed against Brigham Young University, owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Student Madi Barney's complaint alleges the school denied her access to services after she reported to Provo police that she'd been raped.

Complaints generally must be filed with the education department's Office of Civil Rights within 180 days of the last discriminatory act. The complainant and recipient will be informed if the office decides to investigate, according to the department's website.

If a school is found to have violated Title IX, it usually reaches a settlement with the office and must show it is making new efforts to comply with the federal law. Theoretically, a school could lose its federal funding, though Venetis says that has never happened.

In a statement, the Office of Civil Rights said it aims to resolve complaints in 180 days, but it can take longer depending on the case.

The office is typically understaffed, Venetis said, and its employees are overworked and "move at an inordinately slow pace."

Kavalam, who works for a nonprofit in Atlanta, plans to return to campus Thursday to participate in a graduation ceremony.

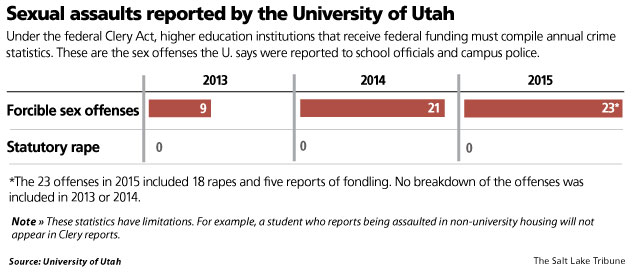

Because Kavalam's assault occurred off-campus, it's unlikely to be included in the school's annual Clery Report, campus crime reports the university is federally mandated to compile.

aknox@sltrib.com, astuckey@sltrib.com

Twitter: @anniebknox, @alexdstuckey