This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Brigham Young University's announcement this week that students reporting sexual assaults will be granted amnesty for Honor Code violations that occur near the time of the assault marked the latest evolution in its student standards, which began to take shape shortly after the school was established in 1875.

Here are some of the more interesting and important developments in the history of student conduct regulations at the Provo university, owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

This timeline is based chiefly on the books "Brigham Young University: A House of Faith," by Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis, "The Lord's University," by Brian Waterman and Brian Kagel, and, to a lesser extent, documents from the archives at BYU and articles in BYU's student newspaper, The Daily Universe and The Salt Lake Tribune.

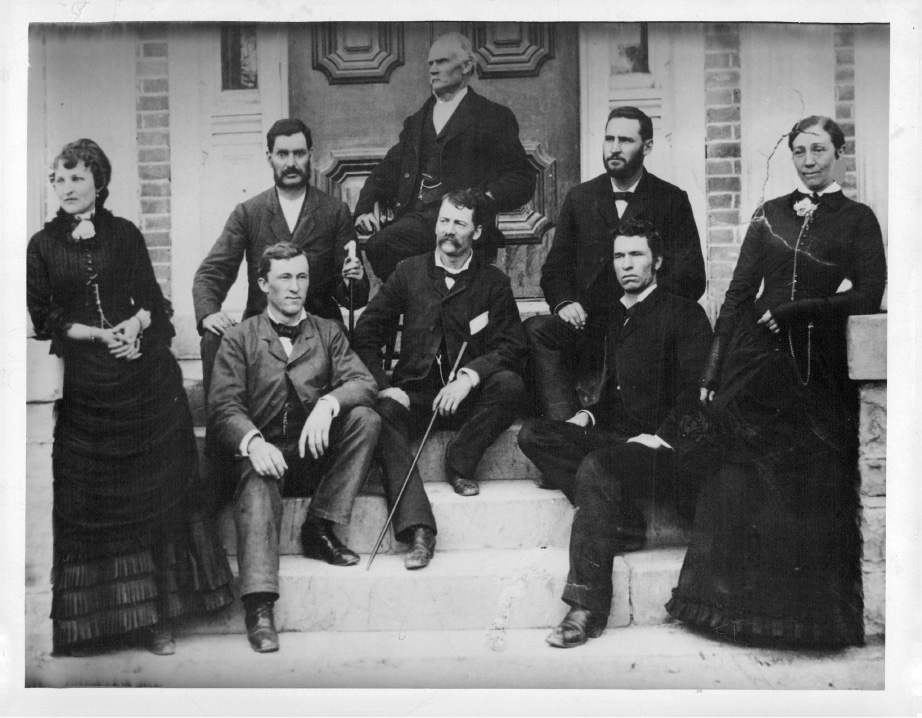

1876 • On April 24, Brigham Young Academy President Karl Maeser, regarded as the school's founder, tells his first class of 29 students that he trusts they will not betray his confidence in them: "I put you all on your word of honor."

c. 1878 • The school's third academic year is "the black year of this academy," Maeser will later say, when the behavior of the students leads him to ask local boarders "to give the students one more trial."

c. 1880 • Maeser creates the Domestic Organization to ensure that students follow the rules — no studying on Sundays, and no smoking, drinking, vulgar language or loitering — while they are off campus. Faculty are tasked with checking in on students at their residences. Says Maeser: "Some may think it none of my business where they are or what they do when out of school, but that is the law of the academy, and if they wish [it] to be none of my business, all they have to do is leave."

Domestic Organization, early years • Minutes from Domestic Organization meetings reflect Maeser's concerns about the accumulation of debts, visitation of billiards halls, smoking and loitering ("A young man that will keep a young lady standing out in the cold is no gentleman!").

1924 • President Franklin Harris declares that BYU is "an institution practically without rules," where "[w]e simply expect every student to be a gentleman or a lady, and [we] leave largely to each individual [the] responsibility for doing this as best he [or she] can."

1935 • Students try and fail to create an honor system after complaints of rampant cheating. One BYU undergrad tells the student newspaper it's "almost impossible for an honest student to get a good grade in some classes," because "such devices as race horses [note cards attached to underwear by rubber bands], journals, and even textbooks are employed in examinations by unscrupulous students, and honest students do not have a chance."

1949 • Students draft the first version of the Honor Code. Nine students on an Honor Council can recommend punishments to school administrators. Faculty members are asked to excuse themselves from classrooms during tests, while students are advised to be watchful and to tap their pencils on their desks to warn cheaters. If cheaters persist, students should try to persuade them to self-report before turning them in to the Honor Council. A year later, there will have been six violations, including a student talking too loudly during an exam and another cutting a page out of a library book.

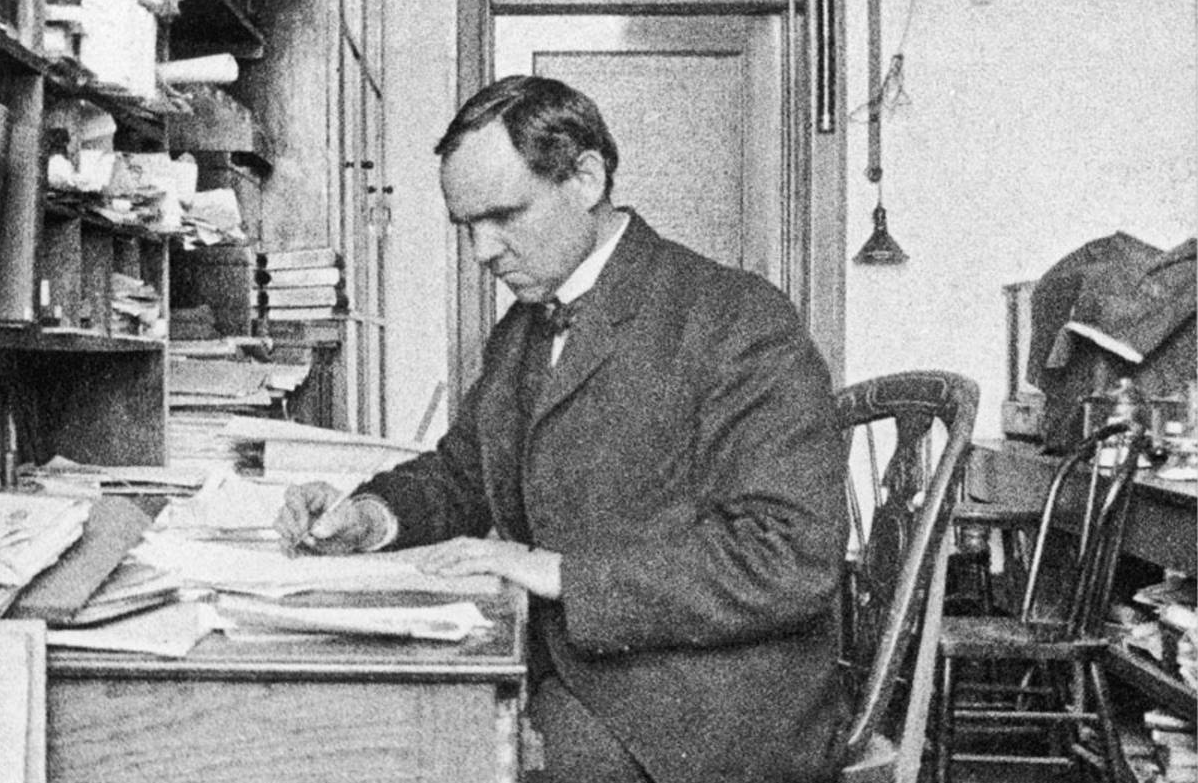

1951 • Ernest Wilkinson becomes school president, a post he will hold for two decades while BYU's numbers of students, buildings and faculty swell by fivefold. Wilkinson will use the school's growth to justify broadening the Honor Code and wresting it from student control.

1953 • Honor Council members wear custom blazers, and students receive wallet-size brochures with cartoons and a tone that is light but not irreverent. "It's no secret that most students find [the Honor Code] unpalatable reading," it reads. "Couched in the necessarily drab language of any official treatise, the Honor Code attracts fewer voluntary readers than last quarter's history text. And yet nowhere in the vast volumes of bookstore and library can be found a more nourishing, savory document." Honor Code reports hit 42.

1954 • Students reportedly chafe at having to sign statements after exams stating that they'd observed the honor system. A student survey finds that only 5 percent of students would tell a teacher the name of a cheater, and only 2.5 percent would tell the Honor Council. Cases triple, to 159.

1957 • Faculty members begin to handle nonacademic matters, and the dean of students, rather than the student body, begins to appoint members of the Honor Council.

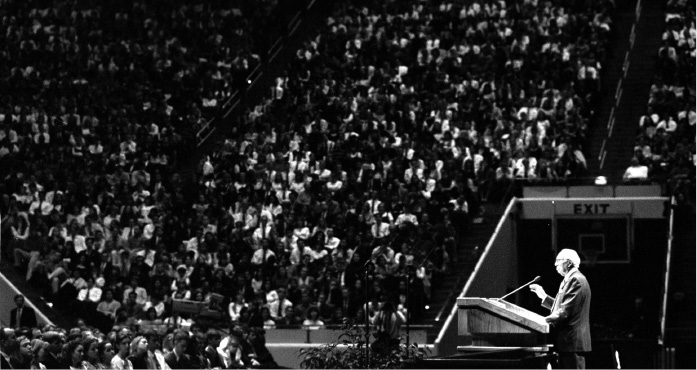

1959 • Wilkinson tells students during a back-to-school address that they have a duty to report their peers' bad behavior: "In certain strata of our society there has grown up the false code that one ought not to 'rat' on friends. ... This is the code of the underworld. It is the code of those who engage in prostitution, other forms of moral debauchery and crime of all description." Students are anonymously polled during fall semester, and about 62 percent report having witnessed cheating. Among the student comments: "There is undoubtedly bound to be some cheating in a school this size; so why don't they just accept the facts and quit trying to make this a 'heaven on earth' school," and "Make no attempt. Man's very nature is depraved."

1965 • After an unsuccessful U.S. Senate run, Wilkinson returns to BYU and derides "go-go girls," "their pseudo-sophisticated friends" and "surfers," announcing that women at BYU should not wear slacks in academic or administrative meetings. He tells students in his fall address: "[W]e do not want on our campus any beetles, beatniks or buzzards. We have on this campus scientists who are specialists in the control of insects, beetles, beatniks and buzzards. Usually we use chemical or biological control methods, but often we just step on them to exterminate them. For biological specimens like students, we usually send them to the dean of students for the same kind of treatment."

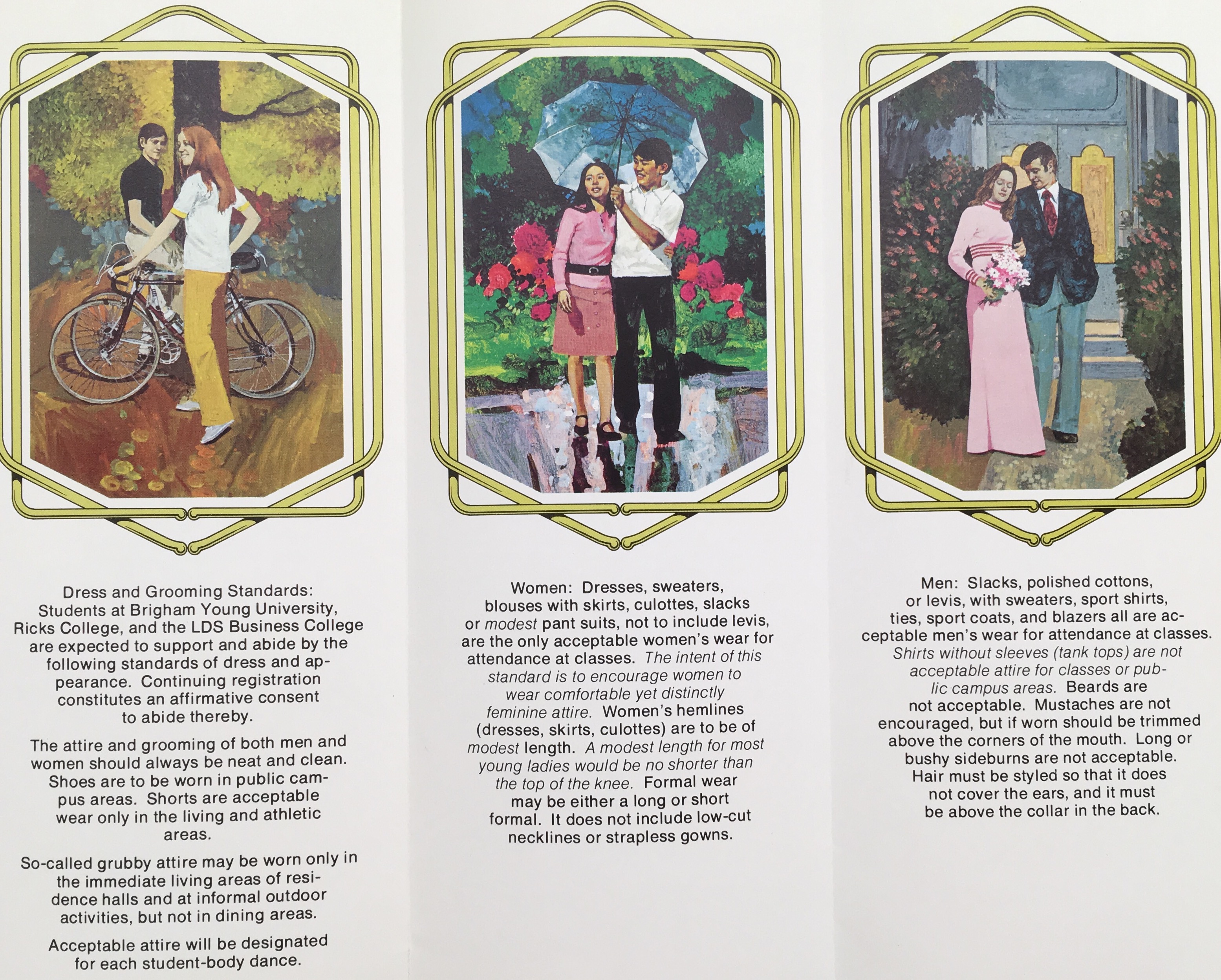

1967 • The administration seizes disciplinary authority from the Honor Council and the code is revised so that it includes drug use and applies to faculty, too. Wilkinson gets board approval to ask LDS stake (regional) presidents and bishops for reports on BYU students. Skirts must now cover the kneecap and cannot be form-fitting, while strapless dresses, spaghetti straps and pants are forbidden. Wilkinson tells students in September: "Last week I saw only one girl on this campus with a miniskirt and she didn't have anything to show." But Wilkinson doesn't get everything he wants: A revised version of the code printed in September's faculty handbook includes the truncated phrase "The church does not approve of any form of — ." The missing words are "artificial birth control," a ban of which the faith's governing First Presidency has declined to endorse. Conservative radio broadcaster Paul Harvey reports after a late-year visit that BYU's code results in "clear-eyed, happy faces," adding: "Undergraduates don't flounder around trying to discover right from wrong; that has been done for them by the trials and errors of generations past."

1968 • Students arrested for drug use or possession will be automatically suspended, Wilkinson announces, and will not get credit for the semester's classes even if they are later found not guilty. Employees at the student center hand 8½-by-3-inch pamphlets with the slogan "Pardon Me" on the cover to female students wearing too-short skirts. Dress bans now include bare feet and sweatshirts, as well as culottes for women and Bermuda shorts for men, who must keep their hair short. The Honor Code is revised to say "virtue and sexual purity" instead of "high moral standards." Students object when they are excluded from that revising process and a committee is formed that includes the dean, four administrators and six students who write a "BYU Code of Student Conduct" — 15 rules that fall pretty well in line with Wilkinson's wishes. Wilkinson's effort to rid the campus of beards backfires, however, when he writes to parents of incoming freshmen that their sons should be cleanshaven. The Associated Press misreports that Wilkinson has banned beards, and after BYU issues a news release to say that beards are still permissible, the school newspaper reports a rise in student stubble. In 1969, Wilkinson bans beards.

1970 • Wilkinson continues to bemoan dress length and begins suspending violators of the dress standards after their first offense. The school newspaper editorializes with mock sincerity about the use of the "maxi-coat" to conceal miniskirts in "an effort to undermine the very fabric of our civilization."

1971 • A survey reveals that 40 percent of students violate dress-and-grooming standards, and 85 percent do so knowingly. New BYU President Dallin Oaks tells students this fall, "I am conscious that you cannot make a great university by lowering hemlines and shaving chins. I have no desire to make the razor and the tape measure symbols of my administration."

1978 • In November, a female student is turned away from the on-campus testing center for violating the school's ban on jeans. She goes to the restroom, removes her pants, and buttons up her coat before returning to pass the test wearing nothing underneath but her underwear. The incident receives national attention when she describes her experience in a letter to the student newspaper, but no formal action is taken against her.

1980 • Singer Melissa Manchester objects to BYU's entertainment contracts, which require women to wear bras. Manchester tells a BYU audience: "Frankly, I would be interested to meet the young man who is going to check!" New BYU President Jeffrey Holland says general modesty is more important than the "endless debate as to whether a 'designer jean' is also a slack, or whether the fabric is cotton, polyester or denim, or whether it is colored red, white or blue."

1986 • The fall student directory includes a photo of founding President Karl G. Maeser that has been airbrushed to remove his beard. BYU's unofficial Student Review newspaper offers a solution, publishing a "cut and paste" beard.

1987 • Students are told that beginning this fall, they must obtain an annual ecclesiastical endorsement from their campus bishop. Also this year: A new policy calls for the establishment of resident assistants in approved off-campus housing, but it's nixed after student opposition.

1990 • When President Rex Lee tells students they must attend church all year to receive an ecclesiastical endorsement, the Student Review prints a badge that reads, "I'm here for the endorsement." In February, a student writes in the Review that standards counselors are using "questionable techniques," including amateur psychoanalysis and allowing tipsters to remain anonymous.

1991 • BYU's dress-and-grooming code is relaxed to permit socklessness and knee-length shorts for men, as well as slacks for women. For the first time in decades, the Honor Code does not require that students abide by the dress standards after a March revision emphasizes general principles over rules.

1992 • The code is amended to prohibit use of pornography on the Y-NET system. The Student Services Association forms a 10-member "music appropriateness committee" to scrutinize tunes played at dances and in the university's weight room.

1993 • BYU places six male gymnasts on probation for Honor Code violations and cancels a tour to Japan and Hawaii. Head coach Mako Sakamoto intends to resign until his athletes persuade him to stay. Visiting professor Karl Sandberg writes in the Student Review that the Honor Code has changed since his time as a student in the 1950s. Then, "[h]onor could only arise from within. To think of honor being enforced would have been a contradiction in terms, a loss of confidence in the principle or principals." Now, he writes, "a general obsession in the church with control, and the effect of that control seems to be nothing so much as the ghettoization of Mormon intellectual and social life."

1994 • In spring, the Student Review anonymously quotes current football players who say players drank and had premarital sex with the knowledge of coaches. Students allege that thousands of copies are stolen from the racks. A BYU representative responds that the administration has received no complaints and "as a matter of policy, the athletes are treated the same as all other students."

1995 • In April, BYU expels five football players after they admit to police that they had sex with a 19-year-old woman who accused them of rape. In May, BYU informs condo owners that they are eligible to provide university-approved housing only if they agree to separate men from women and enforce the Honor Code. In July, a Spanish department faculty member tells The Tribune he attended a gay pride march and that he will seek another job after meeting with BYU officials. He winds up at Weber State.

1996 • The right to wear knee-length shorts survives an administrative review under new BYU President Merrill Bateman. BYU's bookstore manager has acquired a national reputation as "the woman from Utah who wants the long shorts," according to a Tribune story.

1999 • Football players tell The Tribune that Bateman believes the program is out of control and has appointed like-minded administrators to oversee the Honor Code's application. Vice President Alton Wade says "there is a possibility that in the past, because of the nature of their role in the athletic department at the university, [football players] might not have been treated exactly the same as any other student or not held to the same standard." "HBO's "Real Sports" reports in September that running back Ronney Jenkins believes his expulsion for premarital sex relates to his status as a black athlete.

2000 • BYU suspends student Julie Stoffer after the 20-year-old appears on MTV's "The Real World" reality show and lives with members of the opposite sex, a violation of the Honor Code.

2003 • The Honor Code Office decides not to suspend a student who is arrested for blocking the entrance of Salt Lake City's Federal Building to protest the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Nonetheless, the student leaves the school, he says, so that it won't face more negative press.

2004 • Four football players are charged with aggravated sexual assault of a Sandy teenager, prompting BYU to study its athletic program's observance of the Honor Code. The study will call for higher admissions standards for athletes and a "structured interview guide" that coaches will use while recruiting and leaves no doubt about the importance of adhering to the code.

2006 • Campus police arrest 29 members of a gay-rights group for a demonstration against the treatment of gay students under the Honor Code, which then read, "Advocacy of a homosexual lifestyle (whether implied or explicit) or any behaviors that indicate homosexual conduct, including those not sexual in nature, are inappropriate and violate the Honor Code." BYU puts five students on probation for the "die-in."

2007 • In March, a mother and son from Kanab are cited with trespassing when they try to deliver a list of concerns on behalf of gay students. In April, BYU changes the Honor Code to read: "Brigham Young University will respond to homosexual behavior rather than to feelings or orientation and welcome as full members of the university community all whose behavior meets university standards."

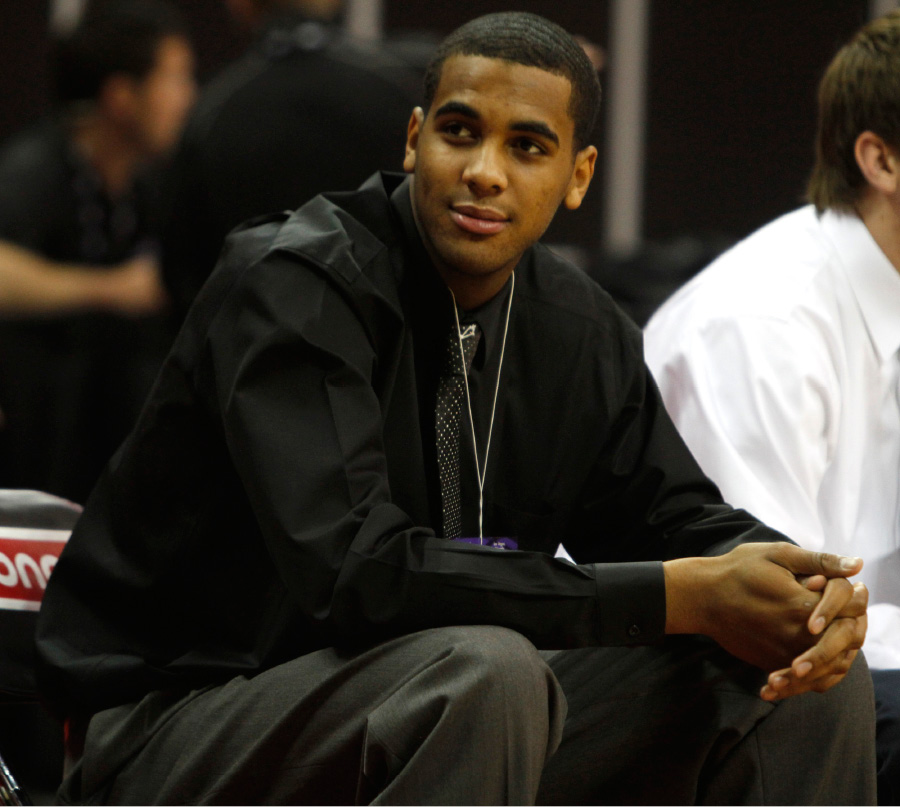

2011 • An investigation by the popular sports website Deadspin.com suggests an uneven application of Honor Code punishments. Of known sanctions imposed on athletes since 1993, Deadspin finds, 54 of 70 punished athletes were nonwhite. Most were black. BYU officials deny the allegation and emphasize that race is not a factor in enforcement. "What matters is whether or not [students'] personal convictions match the principles of the Honor Code," says spokeswoman Carri Jenkins.

2014 • After widespread media interest in Honor Code sanctions against athletes Harvey Unga (2010, football), Brandon Davies (2011, basketball) and Spencer Hadley (2013, football), athletic director Tom Holmoe informs media the school will no longer acknowledge whether a student has been disciplined by the Honor Code Office unless the student has already publicly said so, or the information has in some other way become a matter of public record.

2015 • In March, a group of BYU graduates known as FreeBYU files a complaint with the nonprofit accrediting board that evaluates the school for the U.S. Department of Education. It's not fair, the group says, that while the school allows non-Mormons to attend, church members who leave the faith do so in violation of the Honor Code. The group later files a similar complaint with the American Bar Association, which accredits BYU's law school, and the NCAA. On the heels of a student-organized "Bike for Beards" rally in September, BYU clarifies its no-beards policy: Non-LDS students can wear beards as a requirement of their faith if they have a note from a chaplain, and student actors require a note from the theater department.

2016 • The American Bar Association drops its investigation into FreeBYU's complaint, but a group spokesman believes the pressure has led to small changes to rules for annual ecclesiastical endorsements. Students previously could apply for an exemption only in "unusual circumstances," but now the language has been altered to say that the dean of students "will determine whether the student has observed and continues to observe the standards of the Honor Code" or if there are other "compelling grounds" for an exception. Students may also decline to sign a release giving the school permission to speak with their LDS bishops, and former Mormons are now eligible for admission. Says Jenkins: "We look forward to making continued progress as we pursue our mission of providing our students an outstanding legal education in an atmosphere of religious faith."

Wednesday • After outcry from sexual assault victims who said they did not report attacks because they feared being disciplined under the Honor Code for their own potential violations, such as drinking or breaking curfew, BYU announces sweeping changes in how it will respond to such reports. Among the changes: amnesty for Honor Code violations committed by victims at or near the time of the alleged assault, and leniency for other violations discovered during a sexual assault investigation. The school accepts all 23 recommendations from an advisory council. President Kevin Worthen announces the changes in an email to students, staff and faculty: "We do not have all the answers to this problem, which is a nationwide issue affecting all colleges and universities. But this report provides an excellent framework on which to build."

mpiper@sltrib.com

Twitter: @matthew_piper

—

Karl G. Maeser, BYU's founding president, on "honor"

"I have been asked what I mean by word of honor. I will tell you. Place me behind prison walls — walls of stone ever so high, ever so thick, reaching ever so far into the ground — there is a possibility that in some way or another I may escape; but stand me on the floor and draw a chalk line around me and have me give my word of honor never to cross it. Can I get out of the circle? No. Never! I'd die first."

Source: "The Lord's University"