This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Other historians may know as much about Mormonism's past as Ronald W. Walker, but few, if any, could write about it in the present with as much eloquence as he did.

Walker, who died Monday at age 76 of a rare form of lymphoma, grappled with wide-ranging historical issues, including the fascination with magic among LDS founders, the fateful decision to massacre an emigrant party crossing Utah territory, the rise of spiritualism and seances among the formerly faithful and a nationwide financial panic that almost sank the church.

In the eight books and 50-plus journal articles Walker wrote or edited, he knew how to sustain a narrative arc, get inside the mind of a long-dead Mormon leader, tease out the social dynamics of any episode and empathize with human foibles.

Those skills — plus limitless generosity and an affable personality — made Walker a favorite among LDS, Utah and Western historians, who regularly honored his work and once elected him to lead the Mormon History Association.

There was "no better writer in the LDS historical community," respected Mormon history expert Jan Shipps said. "His death is a huge loss to us in this field."

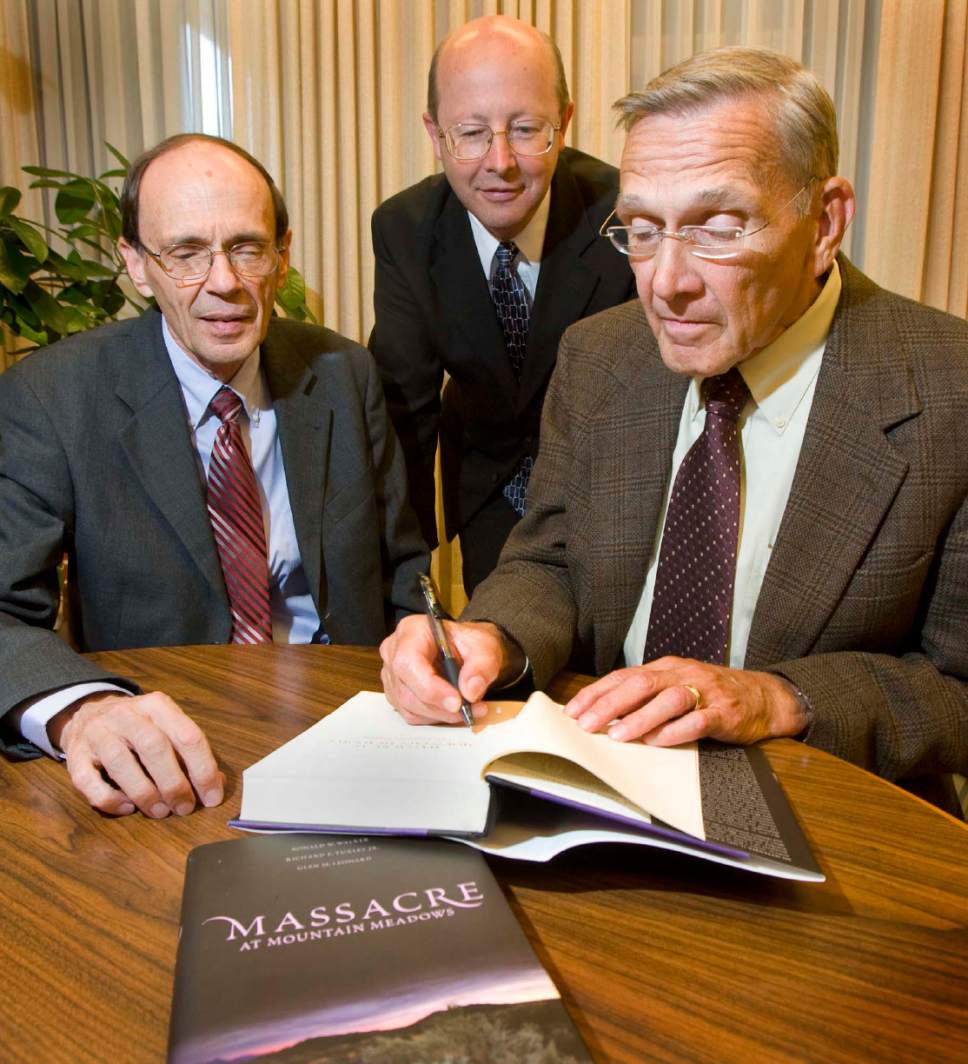

With Walker's passing, Mormon and Utah history "have lost one of their finest and most nuanced narrators," said Richard E. Turley Jr., assistant LDS Church historian, who worked with Walker and Glen M. Leonard on the trio's landmark book "Massacre at Mountain Meadows."

"Ron was a man of faith and intellect who had a talent for recognizing important and often difficult historical events and recounting them in academically precise yet engaging prose," Turley added. "He mentored a generation of historians and left a legacy of fine writing that will engage and inform readers for decades to come."

Born in Missoula, Mont., and reared in Iowa and California, Walker earned bachelor's and master's degrees at Brigham Young University, a master's from Stanford and a doctorate from the University of Utah.

He was hired in 1976 as a full-time researcher during the so-called "Camelot" era of openness in the history department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Four years later, Walker moved with other researchers to BYU's Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History.

After retiring in 2006, the energetic researcher continued his work as an independent historian.

"Massacre at Mountain Meadows," a compelling account of the 1857 murder by Mormons of more than 120 men, women and children in a Missouri wagon train crossing through southern Utah, was a "watershed in the LDS Church's historical conscience," wrote Benjamin E. Park, who this fall will be an assistant professor of history at Sam Houston State University. "The careful attention to social dynamics, the consideration of the viewpoints of everyone involved, and especially the consideration of moral and ethical dilemmas related to the event — these were Walker's expertise, and they were most likely his important contributions."

Patrick Mason, head of Mormon studies at Claremont Graduate University in Southern California, said Walker "had nightmares recounting the horrors of what happened at Mountain Meadows."

"It was never a detached academic endeavor for him," Mason wrote on the LDS blog By Common Consent. "It was wrestling with the worst of our inhumanity, and the struggle to find meaning and reconciliation."

Walker's book, "Wayward Saints: The Godbeites and Brigham Young," was built on his doctoral dissertation, which analyzed the 1860s and 1870s protest movement and the limits of dissent.

"Walker was pulled into these intellectual circles as a way to explore social, cultural, economic and even theological issues," Park wrote on the Mormon history blog Juvenile Instructor. "How far could a dissenter go without drawing serious repercussions?"

At his death, Walker had two unfinished projects: a Young biography, pulling together all his disparate articles and research, and a multivolume look at Mormonism's seventh president, Heber J. Grant, based on about 20,000 notecards he had typed from Grant's extensive journals and correspondence.

"His work left a long shadow on Mormonism's internal historical narratives," Park wrote.

Walker leaves behind his wife, Nelani Midgley Walker, seven children, their spouses, and 21 grandchildren. Funeral arrangements are pending.

Walker was "one of the unsung heroes of Mormon intellectual life from the past 40 years," Mason wrote. "His generosity, graciousness and deep humanity allowed him to approach the past — and especially the people in the past — with both candor and charity."

Twitter: @religiongal