This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Somewhere, Leonard Arrington's ghost has pulled up a chair to eavesdrop on Mormonism's contemporary conversation about controversies in the faith's history.

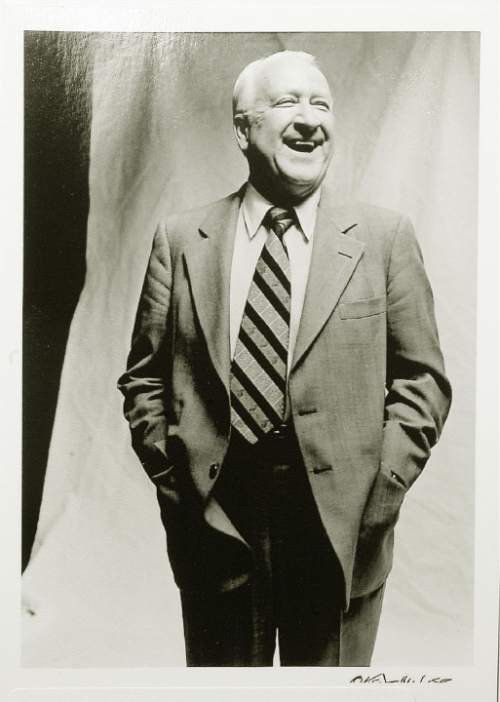

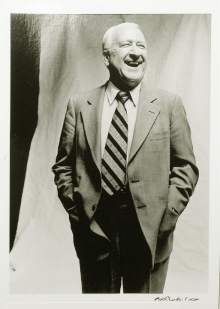

The former LDS Church historian, who died in 1999, likely is smiling, maybe laughing and certainly rejoicing.

But Arrington couldn't have predicted it, says biographer Gregory A. Prince, especially given the struggles the professional historian had in dealing with Mormon ecclesiastical leaders.

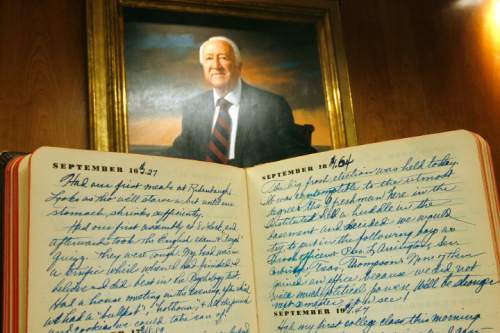

And Prince should know. He read and researched more than 20,000 pages of Arrington's massive journals, correspondence and weekly letters to his kids to produce the just-published "Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History." He also interviewed more than 100 friends, family members and associates to create a full-bodied picture of the man.

"Leonard," Prince says with affection, would "never have dreamed of having access to documents" about some of the church's darkest episodes — including the infamous slaughter of about 120 men, women and children by Mormon settlers at Mountain Meadows — that today's LDS historians take for granted.

Indeed, to the end of his life, Arrington worried that he, too, might face some kind of church discipline for his candid approach to the past.

Arrington lived only six years after the so-called "September Six," Mormon intellectuals who were sanctioned in 1993 for their writings about LDS polygamy, theology, feminism and church authority.

"He thought he was next on the list," Prince says in an interview, "and that he might be excommunicated after publishing his autobiography."

Arrington was never disciplined. In fact, he laid the foundation for Mormonism's scholarly renaissance — including the groundbreaking "Joseph Smith Papers" about the faith's founder, "The First Fifty Years of Relief Society" about its female leaders, and the church's online Gospel Topics essays about thorny historical and theological issues. Along the way, he nurtured many of today's leading LDS scholars.

Arrington's most durable accomplishment, Prince says, is not "what he wrote, but what he did — he mentored hundreds of people at all levels and shaped the future of Mormon studies."

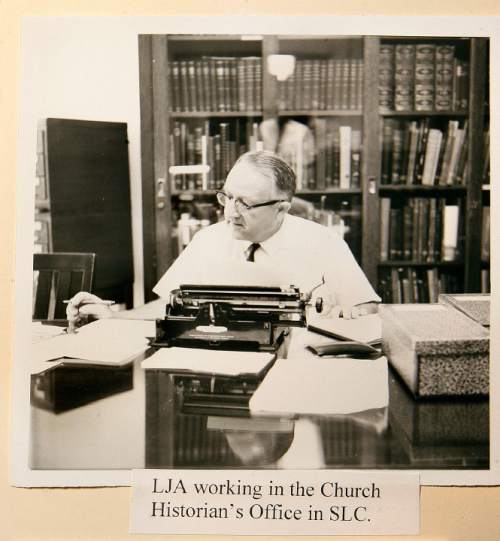

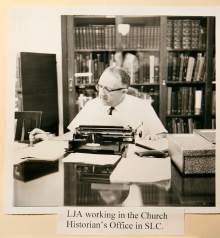

As the church's official historian from 1972 to 1982, Arrington celebrated the life of the mind, believing that reason was no threat to faith.

"Brothers and sisters, I have seen the ... deepest part of the church, and I can tell you that it is inspired," Arrington would tell the Mormon faithful, "and there is nothing in there for us to be ashamed of."

Arrington, a self-described "unorthodox Mormon," had three "epiphanies" that, to him, confirmed the existence of God — the first as a 13-year-old, sleeping under an Idaho moon; the second while in the U.S. Army in North Africa; and the third as he researched his doctoral dissertation (later published as the acclaimed "Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900").

All three produced a sense of connectedness to the divine.

While studying in the library, "a feeling of ecstasy suddenly came over me, an exhilaration that transported me to a higher level of consciousness," Arrington recorded about the last encounter. "I was unexpectedly absorbed into the universe of the Holy Spirit, a gift presumably of the Holy Ghost."

Despite his unbending belief and affable personality, Arrington ran into powerful resistance from powerful players, including a couple of LDS apostles: Mark E. Petersen and Ezra Taft Benson.

The greatest challenge to Arrington's religious convictions, Prince writes, "did not come from the [materials] he read, but from the people above him in the church hierarchy."

Some Mormon leaders attacked the historian's projects, his professional approach, even his faith.

Benson, who would become the 13th president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, once blocked Arrington from the chance of being a mission president in Italy — he had served there during World War II — due to the historian's support of the independent Mormon journal Dialogue.

Arrington lost an "opportunity of preaching the gospel in Italian," Prince says, which the historian accepted "without bitterness, but with palpable regret."

Higher-ups also scuttled Arrington's plan for a 15-volume sesquicentennial history of the LDS Church and criticized several books coming out of his department. He was informed that topics such as the now-abandoned practice of Mormon polygamy and the now-discarded ban on blacks in the priesthood were off-limits.

"Almost daily, [Arrington] interacted closely with full-time ecclesiastical leaders who were accustomed to receiving deferential attention because they were presumed to have special insights into God's will," Prince writes. "Correspondingly, they were often unaccustomed to working through a problem that required organized information and persuasive argumentation, since their ecclesiastical position allowed them to preclude discussion."

Prince "was surprised to see how unaware Leonard was of church [insider] politics. He didn't see the opposition coming and had no defense for it when it did come."

Eventually, the "naive" Arrington was "released" as church historian, and his team of researchers were moved in 1982 to LDS Church-owned Brigham Young University. It marked a demoralizing and disheartening end to a "Camelot" era for Mormon scholars.

"The attempt to suppress problems and difficulties, the attempt to intimidate people who raise problems or express doubts or seek to reconcile difficult facts, is both ineffective and futile," Arrington wrote to his children. "It leads to suspicion, mistrust, the condescending slanting of data."

The more Mormons "deny or appear to deny certain demonstrable 'facts,' " he told them, "the more we must ourselves harbor serious doubts and have something to hide."

Ironically, such an appeal to openness, says Prince, is now embraced by top Mormon leaders and is evidenced in the faith's essays, lesson materials and sermons from the pulpit.

pstack@sltrib.com Twitter: @religiongal —

Who was Leonard Arrington?

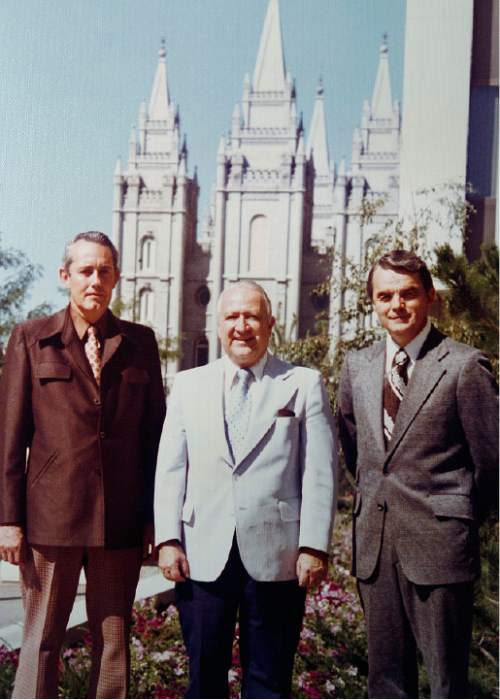

Leonard Arrington was an Idaho farm boy who became a leading LDS Church historian before dying at age 81 in 1999.

Author • He wrote dozens of articles, essays and books, including the critically acclaimed 1958 "Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints" and the 1985 biography "Brigham Young: American Moses."

Historian • He was the first professional to be appointed church historian, in 1972, but saw LDS leaders dismantle the history division and move it to Brigham Young University. The current renaissance of scholarly Mormon history writing owes much to his lasting influence.

Founder • He was a founder of the Mormon History Association, an advisory editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought and encouraged hundreds of scholars through personal letters.

'Beloved mentor' • Arrington is buried in the Logan Cemetery next to his first wife, Grace, who died in 1982. Of all his accomplishments, his children chose one to be etched on his gravestone. It reads "beloved mentor."

Salt Lake Tribune archives