This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

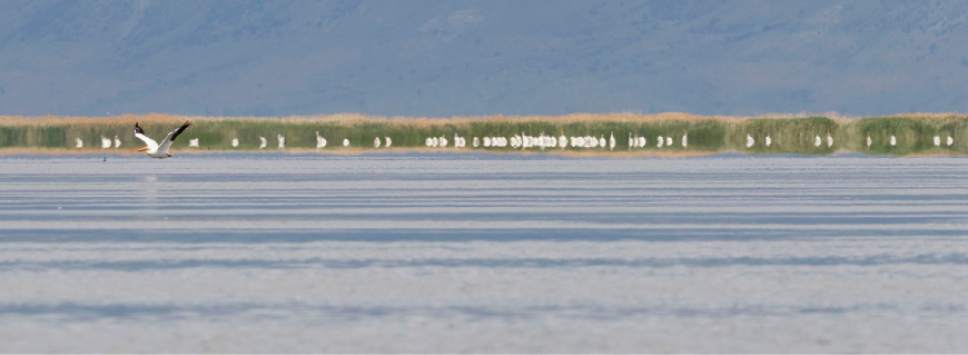

John Ferry's farm and ranch occupies a large piece of Box Elder County along the Bear River, but the family has held a slice for ducks, deer and other wildlife that congregate in the fecund delta where the river meets the Great Salt Lake. This week the Ferrys donated a conservation easement on this land to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), inaugurating an ambitious plan to keep agricultural lands in agricultural hands in one of the West's most biologically rich landscapes.

The Ferrys' donation is a 30-acre drop in an ocean of conservation need, but it officially triggers the establishment of the 565th unit in the nation's network of wildlife refuges, known as the Bear River Watershed Conservation Area. Three years ago, FWS laid out a vision for conserving private lands by tapping the Land and Water Conservation Fund to acquire easements on up to 920,000 acres of private land. Such limited-interests easements allow agricultural lands to remain in production while blocking them from being developed.

Securing an easement was necessary to get the program off the ground, according to Bob Barrett, manager of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.

"It's a small seed and small start, but it will grow into a larger and comprehensive conservation footprint," Barrett said.

The program has so far secured $2 million in funding to begin buying easements from willing sellers, but officials do not know many acres that money can protect. The value of these easements depend on the development potential, and FWS is avoiding areas facing the greatest pressure from developers.

"The story begins today. It is really about outreach and community conversations. How do we have a long-range view for these landscapes? These projects take a long, long time and they are about partners on the land. They are to protect a way of life," Barrett said.

A prominent Box Elder County ranching and farming family going back five generations, the Ferrys, based in Corinne, were not interested in monetizing the development value of their wetlands, located just north of the bird refuge.

"Our philosophy is you need to identify your greatest resource and that's the land. You need to listen to what the land is telling you," John Ferry said. "There's such a corrosive environment with public lands and operators on public lands. Hopefully we are a breath of fresh air. ... When the land is healthy and wildlife is healthy, farming and ranging are healthy. You can have both."

The Bear River cuts a 500-mile arc from its headwaters on the Uintas' North Slope, through southern Wyoming and Idaho before returning to Utah and emptying into the Great Salt Lake west of Brigham City.

Much of the bottom land is privately owned, traditionally used for agriculture, but is now under pressure for residential and commercial development as well mineral extraction and water diversion. Private organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy and Trout Unlimited, and state agencies administer thousands of acres of conservation easements and habitat rehabilitation projects.

The FWS conservation-easement program seeks to coordinate these efforts and add to them. The goal is to acquire new easements on migration corridors, critical habitat and lands that connect these areas in a region that is still relatively open, but developing fast.

"If you look at landscape projects, they really are a collaboration. No one entity has the resources to take on landscape-type work. Our greatest partners is the farmer-rancher. They are the ones tied to the land best." Barrett said. "We don't want to change their operations yet have good stewardship to protect the resources and their lifestyle."

Two other national wildlife refuges preserve habitat upstream — Cokeville Meadows in Wyoming, and Bear Lake in Idaho. But these refuges cover only a tiny portion of the 93,000-square-mile area drained by the Bear, and by themselves cannot preserve the watershed's biodiversity, which includes 200 bird species and dozens of mammals.

"It is through partnerships with conservation-minded private landowners, like the Ferry family, that together, we will find our greatest success in conserving these important landscapes for both people and wildlife," Noreen Walsh, FWS regional director, said Tuesday at a gathering at the refuge. "The Ferry family are private landowners who are models for conservation. Through this easement donation, they join [FWS] in showing that once again, working landscapes and conservation are not mutually exclusive endeavors."

Ordinarily no fan of federal conservation efforts, Utah Rep. Rob Bishop weighed in favorably on this project, praising it for leaving control of the land in local hands.

"In many of the programs we have, if they are driven by local concerns and need, they can be a benefit," said the Republican who chairs the House Natural Resource committee and attended Tuesday's event. "Land conservation projects are an example of programs, that when locally controlled, allow the agricultural community to use their land and preserve a lifestyle that otherwise would be endangered.

Yet this conservation program would have no funding had Bishop gotten his way on one of his many efforts to reduce federal control of the land. Earlier this year, he attempted to block reauthorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund , the 50-year-old program that sets aside federal mineral royalties from offshore drilling to acquire sensitive habitat and areas valued for recreation.

In a compromise, Congress reauthorized the fund, but for three years only, and at half its full level.

But the Ferrys' easement isn't costing taxpayers a dime. John Ferry has no idea what the development potential on his 30 acres would be worth, and doesn't want to know. Donating the easement won't change his ranching practices, but it will ensure this ground will remain wetlands, supporting wildlife, in perpetuity.

"It's not for sale. I don't want to struggle with how much money we could have gotten," said Ferry, whose son Joel is raising his family on the farm. "It's not just land, it's a heritage and it's a legacy. I want to make sure it passes down to next generations. I'm not going to return from my grave 20 years from now and see a hotel on it."

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713. Twitter: @brianmaffly