This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • In this regular series, The Salt Lake Tribune explores the once-favorite places of Utahns, from restaurants to recreation to retail.

—

ZCMI loved to proclaim that it was America's first department store.

For 132 years, it enjoyed a reputation for quality. Vogue, Mademoiselle, Glamour and Seventeen magazines held fashion shows there, and made it their exclusive local outlet. Flashy window displays won international awards.

ZCMI developed innovations such as the Intermountain West's first elevators and escalators, its first big display of electric lights (two years after Thomas Edison introduced them), the region's first delivery fleet and even its first parking garage.

Patrons included rich and common folk.

Celebrity shoppers included actor Bob Hope, pianist Liberace and singer Dionne Warwick. Former British Prime Minster Margaret Thatcher once enjoyed high tea in the downtown Salt Lake City store's Tiffin Room, amid its chandeliers, linen tablecloths and waitresses in uniform.

ZCMI — Zion's Cooperative Mercantile Institution — sprung from a pioneer-era conflict between Mormon and non-Mormon business interests. Mormons then were even threatened with excommunication if they did not support the store. (It was among the reasons that some founders of The Salt Lake Tribune lost their church membership.)

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which owned a majority of the store's stock, sold off ZCMI in 1999 — and for a time, stores operated under the Meier & Frank name, and later switched to Macy's.

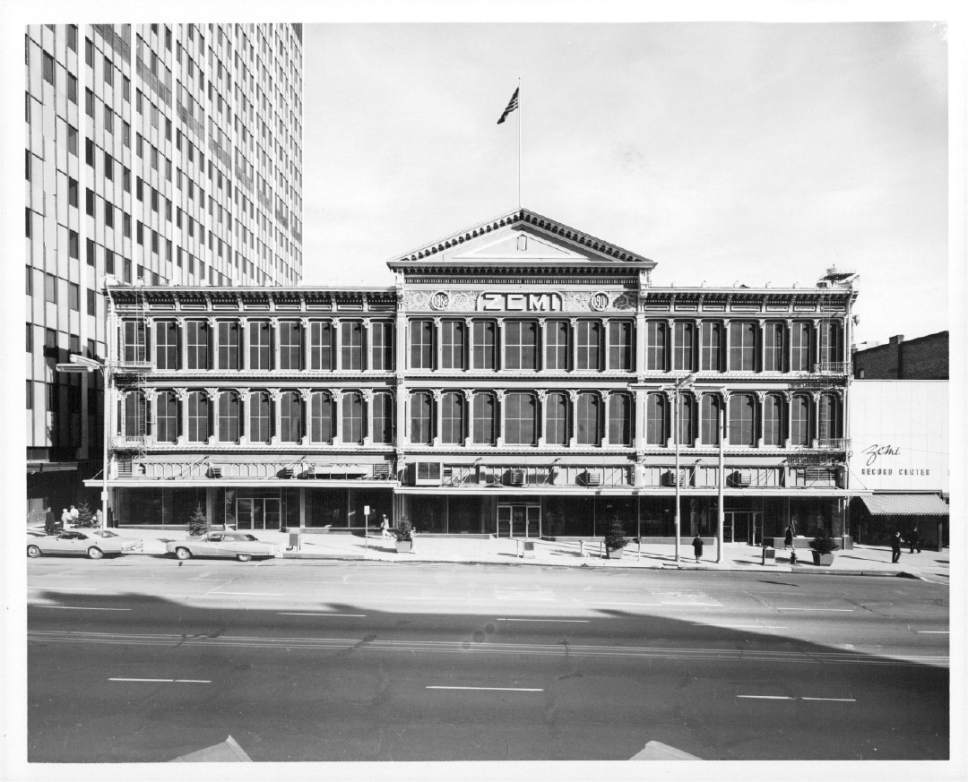

The only place the ZCMI name remains is atop the ornate iron facade from the old flagship store that still decorates City Creek Center.

—

LDS vs. gentiles • ZCMI started as a defense against "gentile" merchants, or non-Mormons, who early LDS Church President Brigham Young accused of price gouging. It also was designed to build LDS unity as completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 threatened to intensify outside influences.

Former LDS Church historian Leonard Arrington noted in the book "Great Basin Kingdom" that most merchandising in Utah "was in the hands of non-Mormons because of the stigma attached to 'profiteering Saints,' and because of the inability of Mormon traders to refuse credit to their 'brethren' and force the payment of debts."

In a September 1868 speech, Young suggested that Mormons should not "trade another cent" with a man "who does not pay his tithing and help gather the poor, and pray in his family."

The next month, the School of the Prophets — a group of local adult male LDS church leaders — voted that "those who dealt with outsiders should be cut off from the church," as a last resort.

In the October 1868 church General Conference, Young received a vote from members to seek to be self-sustaining with their local industry and stores.

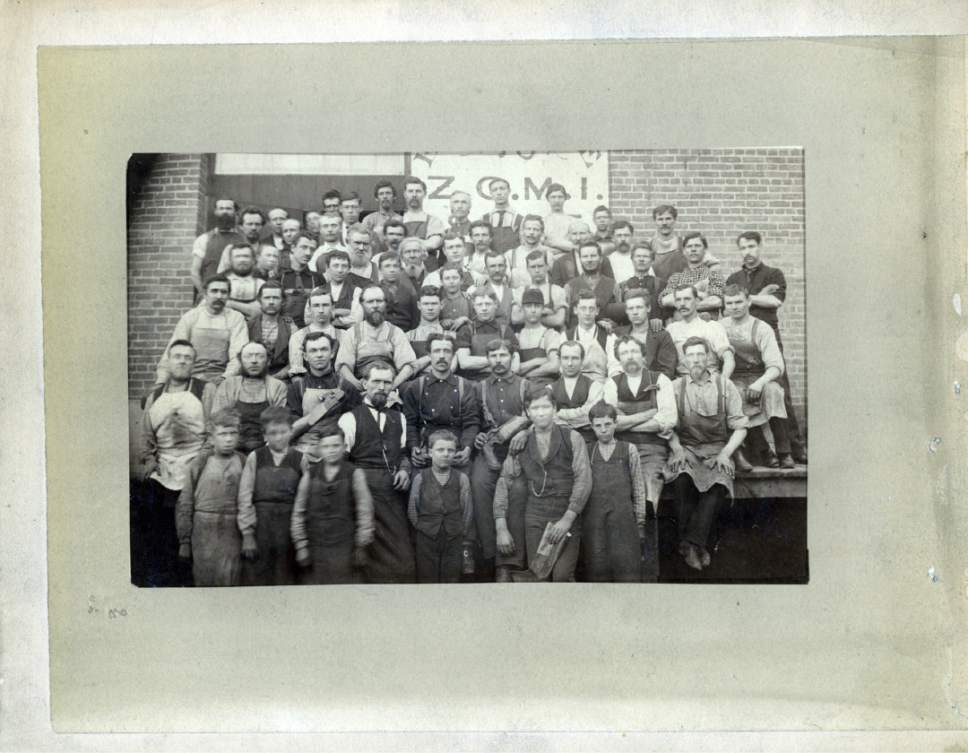

Within weeks, church leaders formed ZCMI.

Young said it was "to bring goods here and sell them as low as they can possibly be sold and let the profits be divided with the people at large" by purchasing directly from manufacturers. It would especially promote Mormon industry and goods.

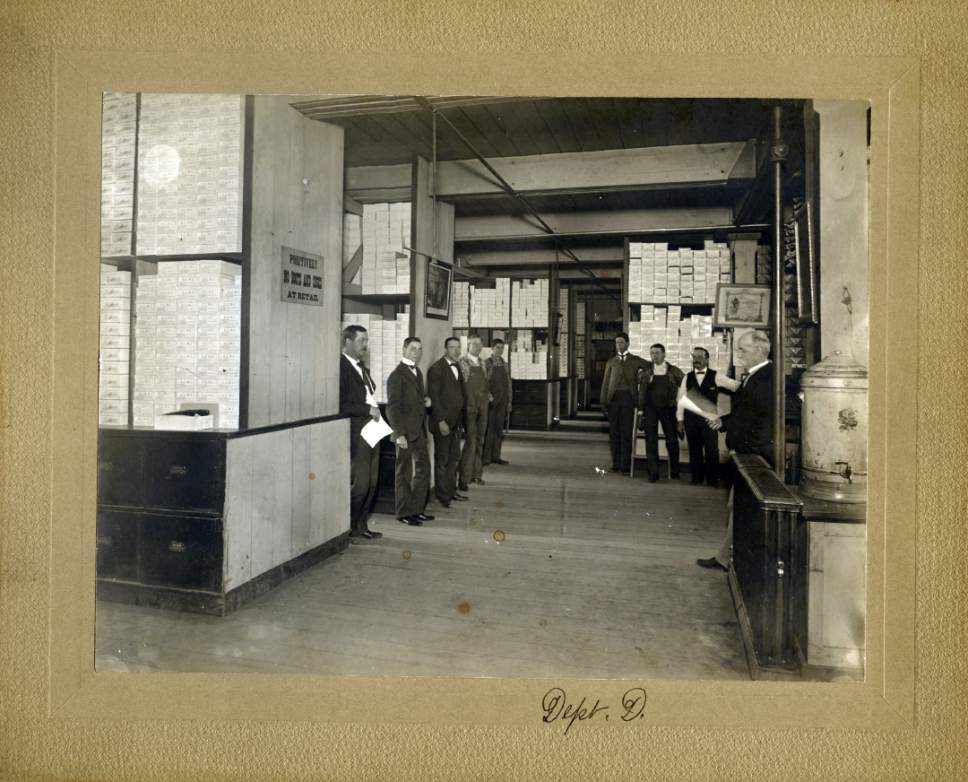

The mercantile institution would operate both retail stores and a wholesale operation. It would distribute goods to "co-op stores" in each LDS ward, or congregation, for sale at set prices (reportedly to ensure uniformly low prices instead of uniformly high ones).

ZCMI opened for business on March 1, 1869, in what had been the Eagle Emporium in downtown Salt Lake City. Brigham Young made the first purchase — for $1,000 worth of products.

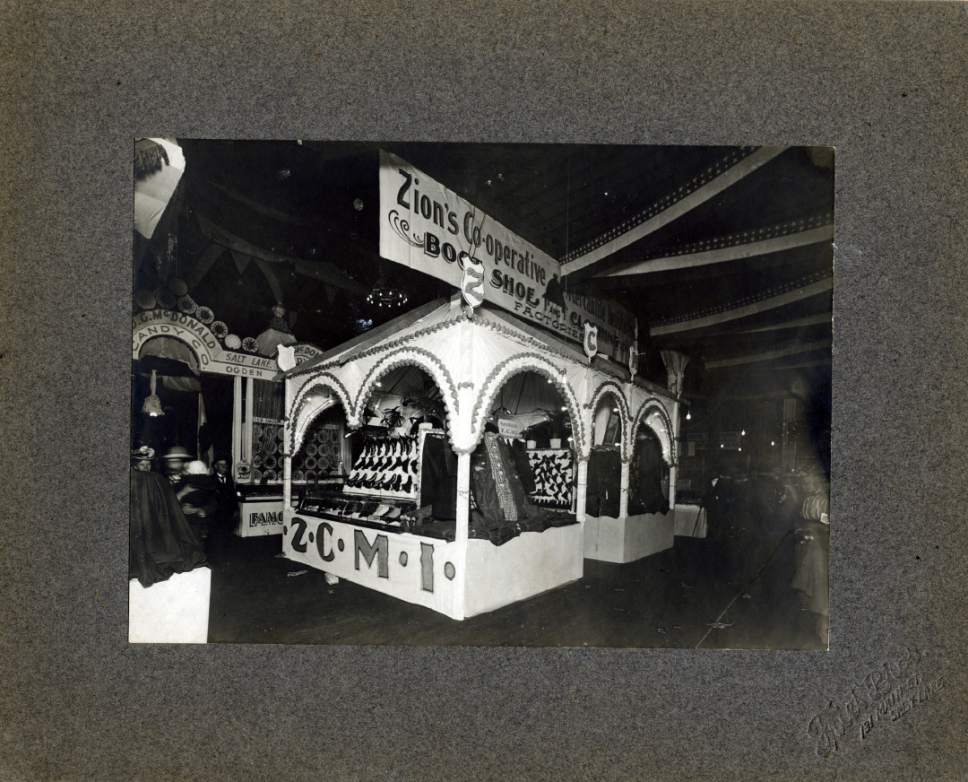

The store offered dry goods, clothing, hats, boots and shoes. Ten days later, another store opened in the Old Constitution Building, which carried groceries, hardware, stoves, Queen's Ware and farming tools. Both were wholesale establishments.

On April 21, 1869, ZCMI opened its first retail store on Main Street. A drug store opened that November.

ZCMI would soon supply 146 co-op stores in 126 settlements in Utah territory.

Young ordered signs for all ZCMI stores that said, "Holiness to the Lord," with the all-seeing eye of Jehovah beneath, along with the words "Zion's Co-Operative Mercantile Institution." (The signs would be removed decades later when the stores tried to broaden their reach to non-Mormon customers.)

Mormon business owners were pressured to sell or merge to become part of ZCMI, and most did. Among those who resisted were some founders of The Tribune, who were excommunicated for that and a variety of other acts and criticism seen as apostasy.

—

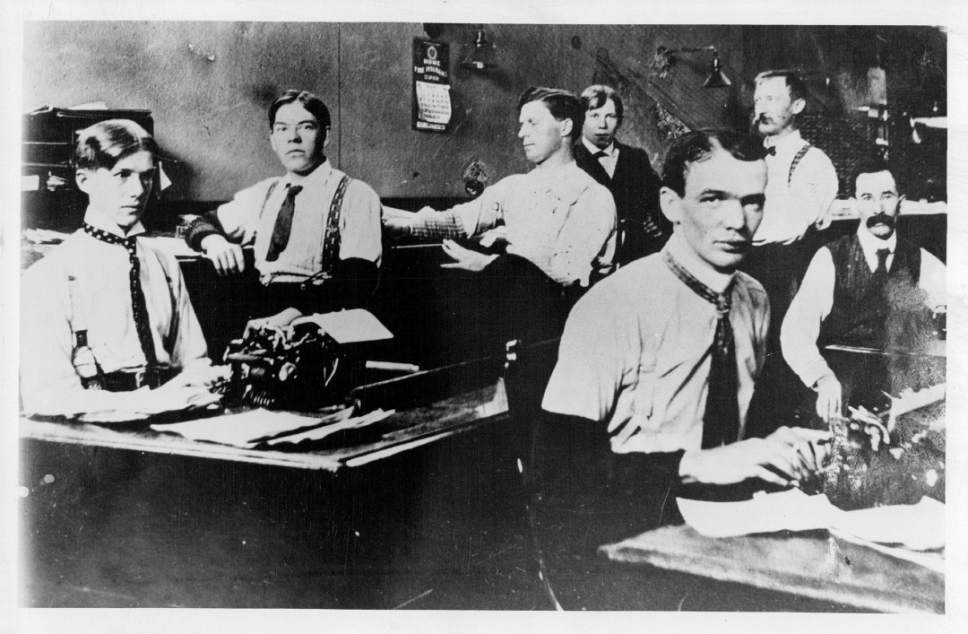

Early success • ZCMI was busy and successful in its early days. A company history said that its oil lamps burned until 10 p.m., or until the last customer was served.

At first, it had no cash registers. Money was dropped into large black kettles under the counters. When the kettles were full, clerks carried them to an office where the income was counted.

Non-Mormon competitors complained that Mormon loyalty to ZCMI was destroying them. Arrington wrote that "the apostate Mormon firm of Walker Brothers, for example, alleged that their sales decreased in a brief space 'from $60,000 to $5,000 per month,' and that those of the Auerbach Brothers fell off in like ratio."

Both firms reported they offered to sell their property to ZCMI for 50 cents on the dollar and leave the territory, but said the offer was refused. Arrington said their claims may have been exaggerated, based on tax lists for the period.

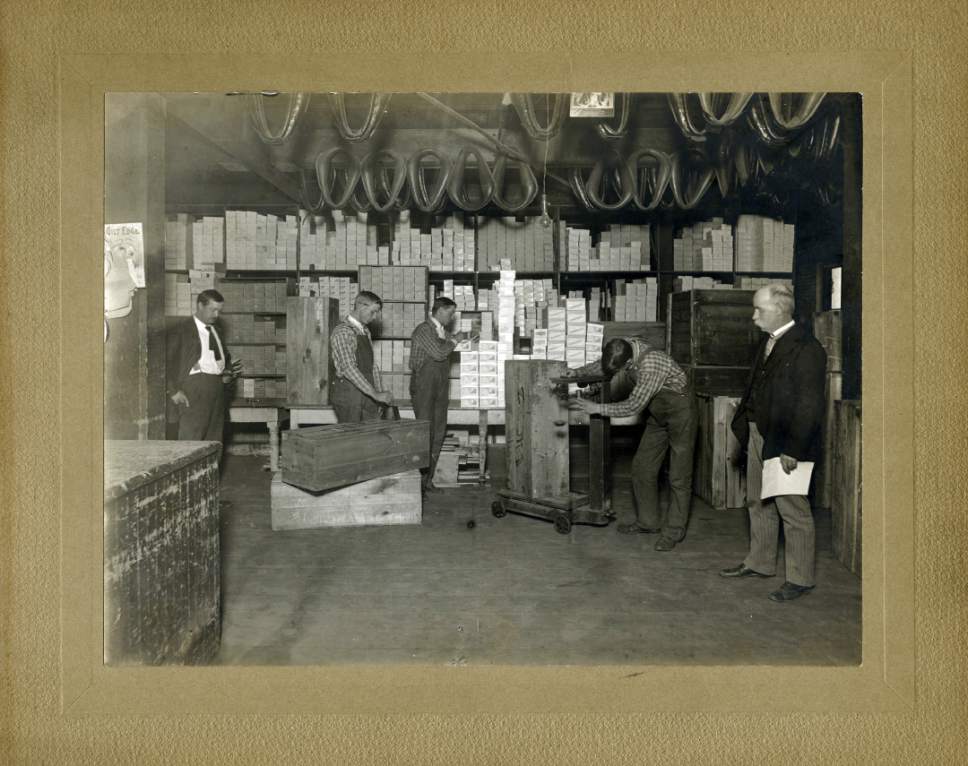

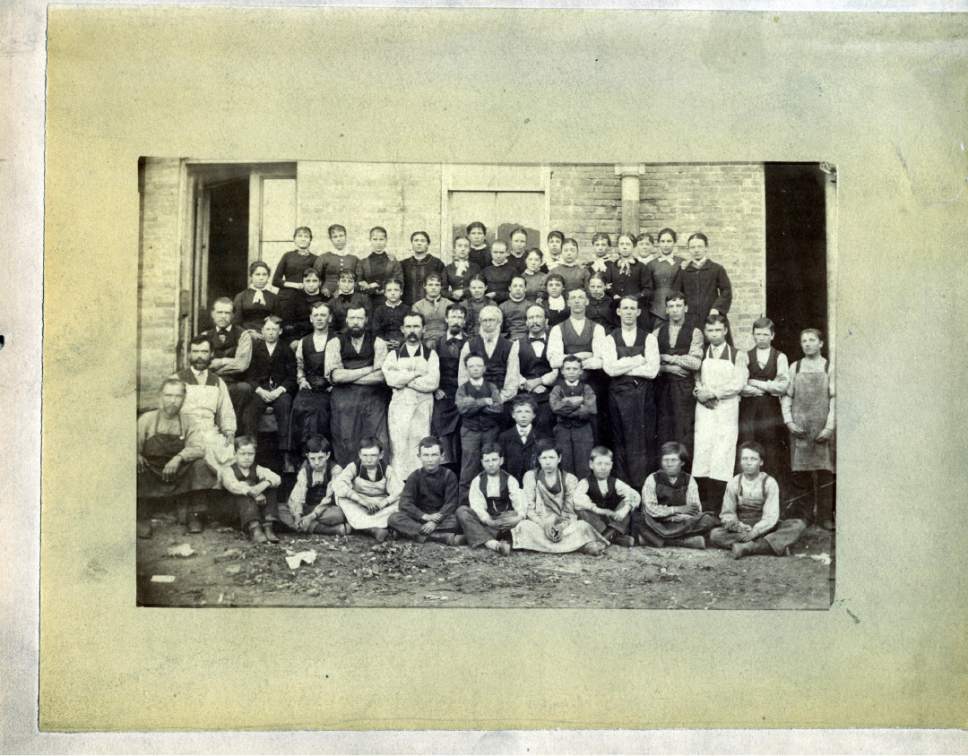

ZCMI used profits to create its own tannery, a boot and shoe factory and a clothing factory. It promoted expansion of cooperative butcher shops, blacksmith shops, dairies, carding machines, gristmills, sawmills, furniture shops and more.

ZCMI operated in a pioneer economy that was almost completely devoid of U.S. currency, so the company printed its own version of money. It adopted the policy of paying its employees one-third in cash, and the remainder in "ZCMI scrip," or orders payable in company merchandise.

The scrip also was often accepted by other businesses at face value.

The scrip resembled money, and Arrington wrote that after 1873, it "was beautifully lithographed in denominations of 25 cents, 50 cents, and one, two, three, five and ten dollars. Approximately $20,000 of these bills, sometime called 'Co-op Shinplasters," enjoyed more or less continuous circulation between 1873 and 1878."

—

Mercantile palace • Before long, ZCMI was in a sound enough position to start building its own facilities.

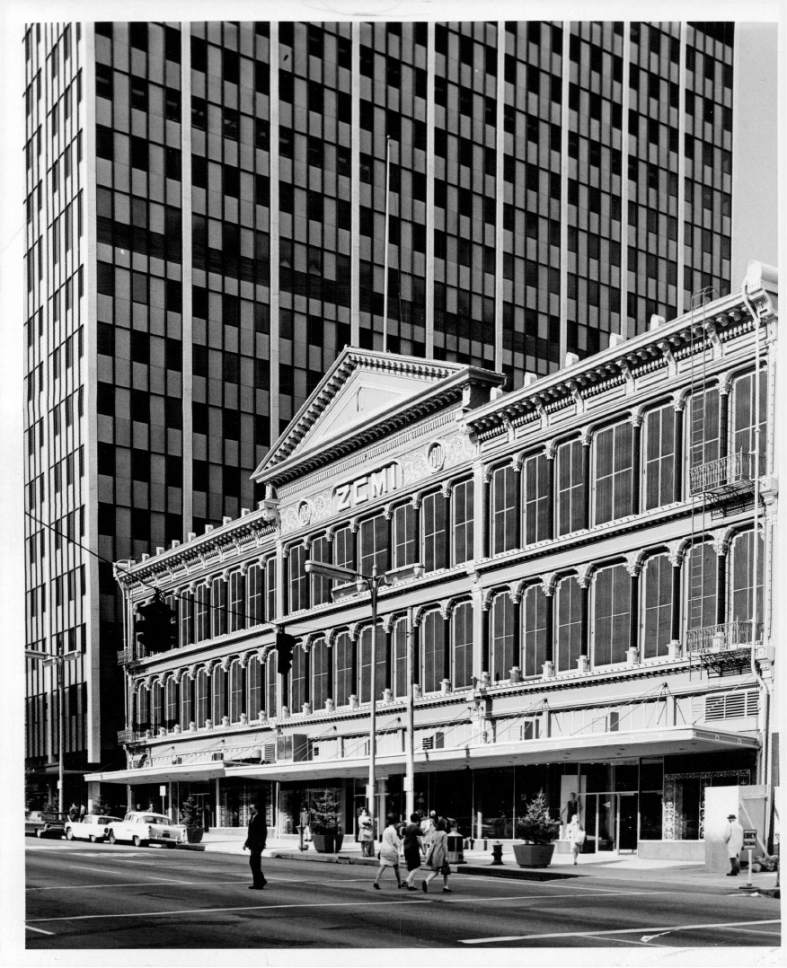

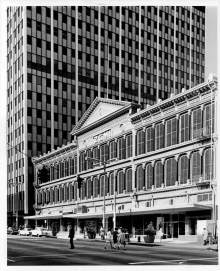

In March 1876, it completed what was described by newspapers as a three-story "mercantile palace" on Main Street between South Temple and First South. All departments were transferred there, except the drug, wagon and produce operations. It would be expanded or rebuilt several times through the years.

Edward Tullidge, one of the founders of The Tribune who left the LDS Church, wrote that the store "will compare favorably with almost any mercantile buildings in America."

Its iron facade would literally become a landmark, and is on the National Historic Register.

ZCMI would always claim to be the nation's first department store. R.H. Macy & Co. started business earlier, but did not become a department store until 1877.

ZCMI would soon be known for innovation. In 1881, it staged a "Festival of Light" with a large display of electric lights, attracting large crowds. In 1884, it introduced hydraulic elevators, the first in the area.

It became the first store in the Intermountain area to have a fleet of delivery wagons, initially horse-drawn ones. It would later have the first fleet of gas-powered trucks.

Some two decades after its founding, ZCMI started to try to expand beyond LDS Church members. In 1891, it ended the practice of sending 10 percent of its cash dividends to the church as a tithing. It started to allow non-Mormons to buy ZCMI stock (although the church and its leaders would retain a majority of it).

The church also ended sanctions against those who shopped with ZCMI competitors. As Utah's population doubled between 1890 and 1920, ZCMI began appealing to all residents, not just church members — including discarding the "Holiness to the Lord" signs. It began hiring more managers with college training and professional experience.

—

Pursuing quality • An ad the company ran for its 125th birthday said, "A major element of our success is quality, which is applied to both the personal and home fashion we carry."

In 1940, Mademoiselle magazine made ZCMI its college-fashion headquarters, and would hold fashion shows there. After 1945, it was Utah's exclusive Vogue store. Glamour and Seventeen magazines would later make it their official store as well.

ZCMI made other innovations that seem routine now, but were big then and enhanced its reputation.

In 1946, Utah Gov. Herbert Maw and LDS Church President George Albert Smith cut the ribbon on ZCMI's new escalators, the first in the area. A company history said, "For some time, the escalators became a playground for children," requiring the store to station a full-time attendant nearby.

On Nov. 1, 1954, ZCMI opened the area's first parking terrace, with 514 stalls on six levels. LDS Church President David O. McKay even led dignitaries on a preview walk through the garage.

The store's Tiffin Room would become the grande dame of Utah's dining scene, complete with chandeliers, white tablecloths, live piano music and waitresses in uniform. Pine pillars circled the atrium.

It was known for open-face roast beef sandwiches, apple Betty, fish and chips and chicken pot pie. A soda fountain with a marble counter and green bar stools offered ice cream sundaes and sodas.

In 1962, ZCMI expanded by opening a store at Cottonwood Mall in Holladay, which the company promoted as "Utah's first complete suburban department store." More would follow in numerous other malls in Utah and Idaho, and other stores would open in Nevada and Arizona.

But ZCMI lost money in the 1990s. Construction of TRAX downtown hurt the flagship store on Main Street. It faced more competition from big box stores in the suburbs.

The LDS Church, the majority stockholder, decided to sell. ZCMI and the May Department Stores approved a merger effective Dec. 31, 1999.

ZCMI became part of May's Meier & Frank chain, and later switched to become part of the Macy's chain.

—

If you have a spot you'd like us to explore, email whateverhappenedto@sltrib.com with your ideas. Find past stories in the series here.

Twitter: @LeeHDavidson