This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

State officials say the Price River is safe for recreation and irrigation and that Rocky Mountain Power should be able to handle any future storms like the one that discharged an estimated 2,700 cubic yards of coal ash into the Price River last week.

Samples collected by the state Department of Environmental Quality in the days following the flash flood indicate concentrations of heavy metals were elevated near the site of the spill, said Scott Hacking, an environmental engineer with the Utah Department of Environmental Quality. Some samples contained twice the amount of metals as collected downstream from the utility's retired coal-fired power plant. None was high enough to violate water quality standards, Hacking said.

Flooding on the Price River kept contaminant concentrations below state standards, Hacking said.

"Because of the volume of stormwater, it just diluted everything," he said.

Drinking water was not affected by the spill, which took place below Price city's water intake point.

Hacking said contractors who were working on-site when the storm hit reported that 2 inches of rain fell in the space of about 40 minutes before the flood.

According to Brian McInerney, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service, flash flooding isn't abnormal this time of year in the Price area. Rainfall in excess of 2 inches per hour could produce an abnormally large flash flood, he said.

The Panther Canyon landfill was equipped with stormwater systems intended to absorb even the sort of major flood that's expected only once in 100 years, but those facilities were under construction at the time of last week's flood, according to Rocky Mountain Power spokesman Paul Murphy.

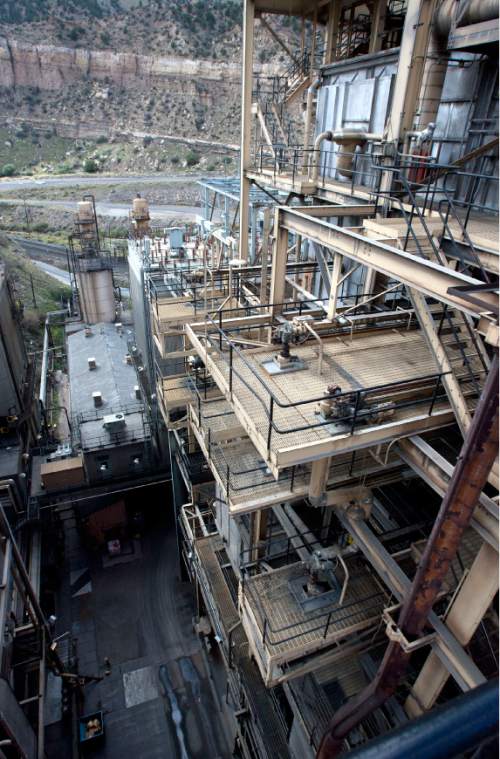

Rocky Mountain Power shipped coal ash from its Carbon power plant to Panther Canyon from the 1960s until the plant closed in April 2015. Since the plant's closure, the company has been working to grade and cap the landfill for permanent closure.

Hacking said the company had installed a temporary 48-inch culvert intended to route stormwater away from a pile of coal ash that construction crews were in the process of moving. When the flood hit, debris plugged this culvert, allowing floodwater to wash over the ash.

Rocky Mountain Power has that temporary culvert functioning again and has positioned a backhoe next to the culvert to keep it clear of debris should any additional flooding occur. The backhoe will remain in place until the ash is resurfaced and capped in about two months. At that point, Hacking said, Rocky Mountain Power plans to reconnect the landfill's permanent stormwater controls.

Hacking said the DEQ is pleased with the utility's response to the incident. He said the state agency believes the landfill's stormwater facilities were designed and sized properly, but thwarted by nature.

But Matt Pacenza of HEAL Utah, which is suing Rocky Mountain Power in federal court alleging that the utility mishandles coal ash waste at its Huntington plant and violates federal environmental laws, said he sees a troubling pattern.

"Several inches of rain isn't an extraordinary act of God," he said. "And I'm pretty sure God didn't tell Rocky Mountain Power to spray coal-ash-contaminated water on fields immediately adjacent to Huntington Creek. What we see is a company that has repeatedly demonstrated carelessness with hazardous coal ash wastes at multiple facilities. Utahns should be concerned."

The Division of Water Quality is currently reviewing Rocky Mountain Power's 62-page incident report, which has not been released to the public. Hacking said it was hard to say at this point how the state will respond, though he said he thought the DEQ would "take into account whether it appears to be an act of nature" while determining whether to pursue compliance action against the company.

Hacking said the state may also have to come up with a long-term monitoring plan for the Price River to ensure the landfill — which contains some 2 million cubic yards of heavy-metals-laden coal ash — doesn't continue to leak into the river after the company finishes capping and reclaiming the site.

Twitter: @EmaPen