This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Blanding • The debate over motorized use in Recapture Canyon reached a critical milestone Friday, one that the Bureau of Land Management hopes will pave a resolution to one of Utah's most embittered road controversies.

The agency released a long-awaited draft Environmental Assessment (EA) for San Juan County's proposed right-of-way through and around the archaeologically rich area that has been a flashpoint in rural Utahns' disaffection with federal land oversight.

The document lays out six alternatives, ranging from granting the county's 12-mile network of motorized rights-of-way to leaving in place a controversial order barring motorized travel in the canyon.

The BLM does not identify a preferred alternative, but whatever the agency decides, its call is sure to anger someone.

"I have resources that have to be managed and laws and policy that have to be followed. I don't think it will bring satisfaction to everyone," said Don Hoffheins, the BLM's Monticello field office manager, who inherited the unenviable task of processing the right-of-way application when he assumed his post three years ago.

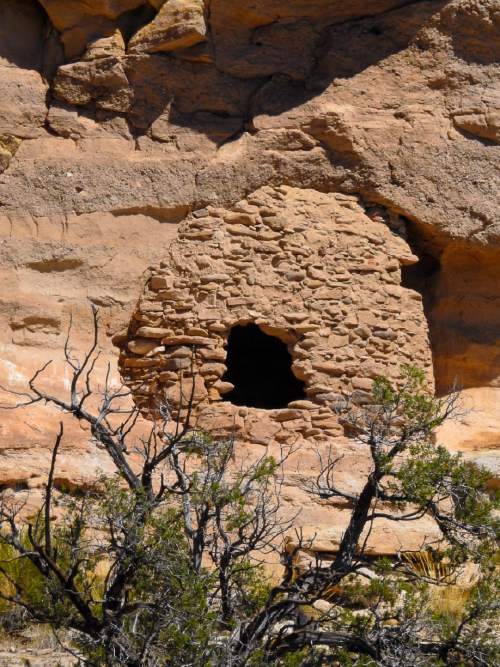

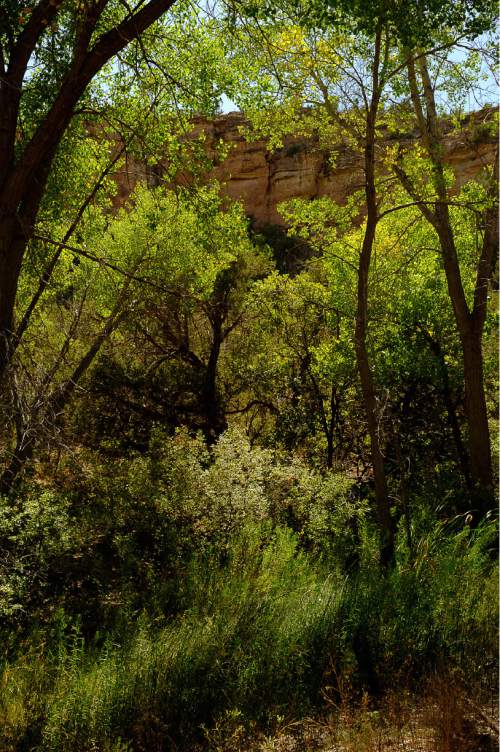

The resources in question are the plethora of artifacts left by ancient American Indians who inhabited the canyon more than 800 years ago, as well as riparian and wildlife habitat.

A public comment period is open for the next 45 days and the BLM will use this input to stitch together a final decision, likely taking elements from multiple alternatives.

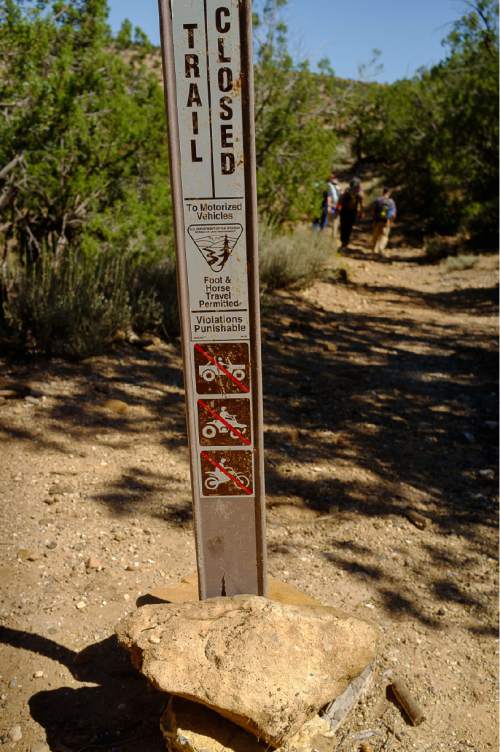

The seeds of the controversy were planted a decade ago when local ATV enthusiasts cut a trail along several miles of canyon bottom south of Recapture Dam, just a few miles east of Blanding. Trail construction crossed numerous cists, middens, hearths and other ancient remnants of the Anasazi occupation, which are barely visible on the ground yet highly susceptible to damage.

In response to complaints from wilderness advocates, the BLM closed the canyon to motorized use in 2007 and prosecuted two local men for cutting the trail. They pleaded guilty and the community helped cover their $35,000 fine.

While environmentalists are pleased an EA is finally out, they say granting a motorized right-of-way, at least along the canyon bottom, would reward those who illegally constructed the route.

"We would also hope the BLM not grant a right-of-way for motorized recreation. That is not a necessary transportation under Title V," the federal statute San Juan is citing for its application. "That would be a terrible precedent. BLM has full authority to designate an ATV trail in partnership with the county without a right-of-way," said Rose Chilcoat, a longtime activist with Great Old Broads for Wilderness. "Our public lands need to serve multiple users. Close to Blanding many places provide motorized use. Very few provide quiet use such as can be found in the heart of Recapture Canyon."

Despite this canyon's easy accessibility, scenery and rich archaeology, it sees little use. Access points are not signed and public agencies do little to promote it. The BLM estimated monthly visitation numbers as between 13 and 90, depending on the season.

By contrast, Kanarraville, another non-motorized BLM canyon near Cedar City, averages more than 3,000 visits a month.

Many Blanding locals feel the BLM has ignored their interests and believe they have a right to drive the canyon. BLM's delay in processing the county's right-of-way application prompted San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman to organize a protest ride in May 2014 in which BLM says 32 riders drove down the illegally built trail before exiting Recapture at Browns Canyon, damaging eight archaeological sites.

Although Lyman confined his ride to an existing road, the protest earned the commissioner a conviction on federal trespassing and conspiracy charges, a 10-day jail sentence and a $96,000 restitution order. His conviction is under appeal.

The BLM hopes to get this dispute behind it, but it must determine whether ATVs are compatible with dozens of archaeological sites protected under federal law and held sacred by many American Indians, including Navajo and Hopi.

Many prefer the canyon remain off-limits to motorized use, according to Mark Maryboy, a Navajo activist who has served on both the San Juan County Commission and the Navajo Nation Council.

"It would be unfortunate if that road should be open [to motorized use]. That's an ancient cultural site that needs to be protected forever," Maryboy said. "Native Americans consider those sites just as important as the cemetery in Blanding. The people who lived there back in the day were very much like us, with feelings and emotions. It is where they lived and laid their people to rest and we have to respect that."

Reached Friday, county commissioner Bruce Adams said he had yet to read the EA and was not yet prepared to comment. In the past, he has complained about the BLM's failure to make a timely decision and threatened to litigate. In 2014, he and Lyman voted to pass a resolution asserting the county did indeed have a "valid existing" right-of-way through the canyon, citing historical use of the canyon as a transportation corridor by wagons and cattle.

In the core part of the canyon, however, there is no evidence of a road except for the 2005 illegally built trail. In one place it cuts within a foot or two of an excavated cist, a below-ground storage vessel formed by upended flat stones arranged in a circle 1 meter in diameter, according to BLM archaeologist Nate Thomas.

"When I come here, there is this thrill of discovery, " said Thomas during a recent visit to the canyon. He noted how the dirt was a darker color in one spot, and potsherds could be seen scattered around the surface.

"A feature like that is important. Obviously there was a hearth here," Thomas said, running his fingers through the blackened dirt in the middle of the trail.

Just above this spot, the trail runs up a steep hill that is badly eroded.

"Is it better to put a trail where there is already disturbance, or is it better long term to build a new trail that avoids disturbance?" Hoffheins asked.

In many places, including the damaged area Thomas highlighted, the answer, according to the EA, is to build a new trail.

Under the county's proposal, the BLM would authorize 4 miles of trail that were illegally constructed. But about 1.5 miles would be rerouted to avoid damaged sites.

Still, the new trail alignment would pass over or beside 21 sites that are eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. These sites would be padded with earthen materials to protect them from trail riders. And seven stream crossings would be "hardened" with rocks to prevent ATV wheels from cutting ruts across the river channel.

In a middle-ground alternative drawn from a proposal offered by Great Old Broads, motorized use would be allowed on the canyon's west rim, but not on the canyon bottom. Instead, an 18-inch-wide trail would be developed from the end of the existing road to Browns Canyon for use by hikers and equestrians.

In another alternative, no trail at all would be allowed, but Hoffheins fears that could spell trouble.

"If you don't define a trail, there tends to be more dispersed use, especially at stream crossings," he said.

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713.

Twitter: @brianmaffly