This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The recently leaked videos of Mormon authorities discussing sometimes-thorny issues behind closed doors exposed no stunning secrets or unexpected statistics.

But they did provide stark visual verification of what believers long have known about their faith's top leaders:

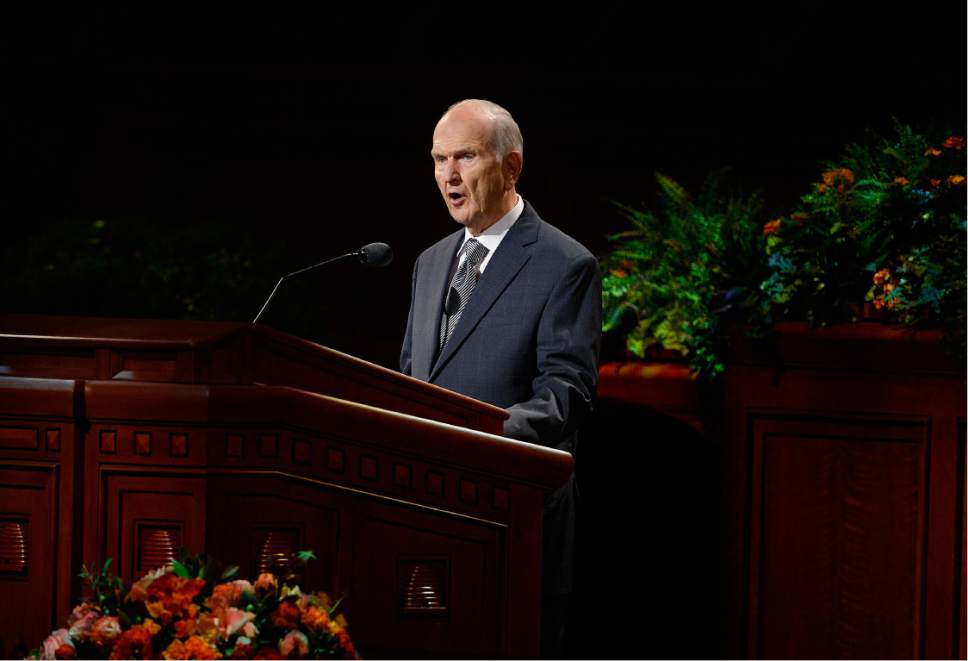

They are mostly older, white and male.

As the camera focused on speakers giving lectures and apostles asking questions — on topics ranging from how to help single members to how to encourage food storage and convert more Muslims — almost no women or people of color were in sight.

And among the apostles, a few were in their 60s, but some were well into their 80s and 90s.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has made some changes since the briefings were filmed between 2007 and 2012. Today, at least one woman sits on three high-ranking executive committees, a few non-Americans have inched up the leadership ladder, and the age of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has dipped a tad.

But the process of picking apostles who eventually could become the Mormon president, considered a "prophet, seer and revelator," remains the same — which almost guarantees the presiding quorums will always be a kind of gerontocracy.

Today's apostles typically are appointed in their 60s. They stay there until death, with the longest-serving man taking the helm of the 15.6 million-member church when his predecessor dies.

That system, some say, can produce problems — including leaders who suffer physical and mental impairments. The current president, 89-year-old Thomas S. Monson, who became an apostle 53 years ago at age 36, is growing increasingly frail and addressed members at the faith's recent General Conference for barely nine minutes.

Some wonder if an LDS Church president could resign his office — the way Pope Benedict XVI did — and hand the leadership to a younger, more vibrant man. Could the church institute a mandatory age — say 85 — at which apostles would be granted emeritus status (as it began doing in 1978 with general authorities in the Seventy)?

The LDS Church says no.

"President Monson ... and others in church leadership are feeling the effects on advancing age," spokesman Eric Hawkins said this week in a statement. "Emeritus status is not a consideration for members of the [governing] First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve."

Some say that can and should change.

—

Is there precedent? • Last year, before the deaths of apostles L. Tom Perry, Boyd K. Packer and Richard G. Scott, the average age of the 15 men who comprised the faith's top leaders was 80, the oldest such cohort in its 186-year history.

Thanks to the three replacements, the average age in the three-member First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has dropped to 76. Four are in their 70s, five are in their 80s, and one, Russell M. Nelson, next in line for the church presidency, is 92.

David A. Bednar, who is 64 and became an apostle at 52, sees wisdom in having gray-haired colleagues.

"The limitations that are the natural consequence of advancing age can in fact become remarkable sources of spiritual learning and insight," Bednar said at LDS General Conference a year ago. "The very factors many may believe limit the effectiveness of these servants can become some of their greatest strengths."

Besides, Hawkins notes, Monson, "who has always been private about his health," is making decisions and the "workload of the First Presidency is up to date."

But Mormon researcher Gregory Prince, author of a forthcoming article on the topic, warns of downsides to reliance on aging authorities.

"A power vacuum at the top, caused by the incapacitation of the church president, can put the entire church at risk of damage that might otherwise be prevented by a competent president," he explained. The top leader also can step in and settle conflicts between apostles and take actions his counselors feel uncomfortable implementing on their own.

"Service until death is a tradition but not a scripturally based doctrine," Prince writes in "Gerontocracy and the Future of Mormonism," slated to be published in the fall edition of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. "Although the tradition has remained in place for nearly two centuries for the [top 15], it was abandoned after nearly a century-and-a-half for [the Seventy]."

It could have happened for apostles in 1970.

Hugh B. Brown was a counselor to church President David O. McKay during much of the 1960s. After McKay died, Brown returned to his place in the Quorum of the Twelve, Prince reports. Brown "attempted to retire and thus set a precedent, but his colleagues blocked his move."

The process of Mormon apostles serving for life "is a legal precedent or tradition," according to LDS historian Matthew Bowman, author of "The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith," "rather than a revelatory dictate."

There's no reason, he says, why the church couldn't allow men to keep their titles as apostle but not continue in the quorum.

"Historically, the Quorum of the Twelve is not equivalent to the apostles," Bowman says. "It is possible to have apostles who are not part of the quorum. Brigham Young ordained two of his sons as apostles, for example, and they were never part of the quorum."

Beyond health issues, though, some see sticking points with top LDS leaders always being men of a certain age and from similar backgrounds.

If you gather any individuals who were all born within a couple of decades of one another and in the same environment, Bowman says, "they would have the same limitations."

The historian was pleased to see the videos showing Mormon leaders educating themselves about concerns of the day. But valuable voices, he says, were missing.

—

Where are the women? • The lack of women participants in the videos proved a powerful reminder to Neylan McBaine, author of "Women at Church," about the need to push for more female involvement at every level.

Bringing women into conversations about how to shape LDS policies is not only the right thing to do, McBaine says, but studies also show it is more effective.

"When you have three or more women on a corporate board," she says, "decisions change and profitability rises."

While McBaine believes God "can open doors to thoughts that these men would not have on their own," she says the church is not fully "using the healing and beneficial resources women could provide."

Catherine Stokes, an African-American who joined the LDS Church nearly four decades ago, would also like to see more diversity among the leadership.

"If you only know one song," she muses, "how do you gain an appreciation and understanding of the breadth of music?"

Stokes would like to see service opportunities spread as widely as possible.

"If expanding the emeritus status would move forward the Lord's work," Stokes says, "I'm sure the Lord will reveal it — in his own due time."

That time, according to the church's statement, is not now.

Twitter: @religiongal —

How old are top Mormon leaders?

First Presidency

Thomas S. Monson, 89

Henry B. Eyring, 83

Dieter F. Uchtdorf, 75

Quorum of the Twelve

Russell M. Nelson, 92

Dallin H. Oaks, 84

M. Russell Ballard, 88 (on Saturday)

Robert D. Hales, 84

Jeffrey R. Holland, 75

David A. Bednar, 64

Quentin L. Cook, 76

D. Todd Christofferson, 71

Neil L. Andersen, 65

Ronald A. Rasband, 65

Gary E. Stevenson, 61

Dale G. Renlund, 63