This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

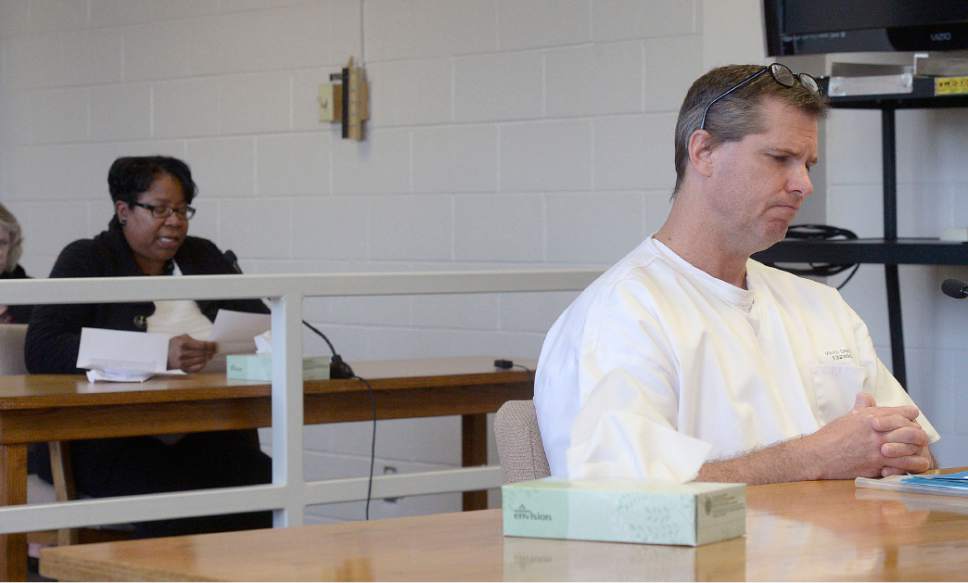

Draper • After asserting his innocence for more than two decades, David E. Mead on Tuesday admitted at a parole hearing that he committed the "unforgivable act" of killing his wife, who drowned in a fishpond at their Salt Lake City home.

In addition, Mead — who said he was having financial problems and being pressured by his mistress — admitted to asking his cousin to kill his wife.

"I was a greedy, greedy miserable human being," he said.

Mead claimed his wife grabbed and struck him on Aug. 15, 1994, after he told her about his mistress as they were standing in their backyard, and he pushed her away from him into the pond. He had walked halfway across the yard when he realized Pamela Mead was not getting up, he said.

"I let her go," Mead told Clark Harms, a member of the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole who conducted the hearing. "I stood there and I allowed her to drown. I let her drown right there in front of me and I walked away."

He then changed his shirt, which his 29-year-old wife had torn in their confrontation, and went to work, Mead said.

"That's what happened on Aug. 15, Sir," he said. "I killed my wife."

In response to a question from Harms, Mead said it took about two to three minutes for Pamela Mead to drown.

Mead, now 49, was convicted by a jury in 1998 of first-degree felony murder and second-degree murder solicitation. Prosecutors said the motive was $500,000 in life insurance and the chance to inherit his wife's business. Third District Judge J. Dennis Frederick called Mead calculating and cold-blooded when he imposed a sentence of up to life in prison.

At the parole hearing, Mead said he had not admitted his guilt previously because he was a coward who was terrified to go to prison. When asked by Harms why he didn't speak up after the Utah Supreme Court upheld his conviction in 2001 and his appeals were over, the inmate said he was ashamed to let his family know what he had done.

A parole decision, which will be made by a majority vote of the five-member board, will be issued later. Harms noted that he is just one member but told Mead he would be "very surprised" if parole were granted.

The victim's sister, Mary Stokes, who attended the hearing, said Pamela Mead was a sweet, loving individual. She asked that Mead never be released.

"You are a predator and a coward," Stokes told Mead. "Maybe if this were a spur of the moment crime I could move past it and forgive but you planned and calculated the crime for a long time."

Howard Lemcke, who prosecuted the case and later wrote a book about it, and Jill Candland, a former Salt Lake City police detective who investigated the case, also were at the hearing. The two, who are both retired, said afterwards that they also believe Mead planned the crime.

The Meads were married in 1991 in Pamela Mead's hometown of Colorado Springs and made their home in Salt Lake City. Shortly before her death, Pamela Mead bought a commercial airplane cleaning business based at Salt Lake City International Airport from her husband's family and took early retirement from her job as a flight attendant.

At first, Pamela Mead's drowning was ruled an accident because it appeared she had slipped and struck her head in the newly built fish pond. She was recovering from bunion surgery at the time and both of her feet were bandaged.

Neighbors saw Mead, who operated his wife's business, leave the home at 8:15 p.m. for the airport. He claimed to investigators that he returned about 11 p.m. to find his wife floating face down in the fishpond.

But two people connected to Mead soon came forward — his mistress, Winnetka Walls, told investigators that Mead had predicted his wife would have "a nasty spill," and his cousin, James Hendrix, said Mead tried to hire him to kill his wife or find a killer.

Mead at that time was trying to collect the $500,000 in life insurance, but his wife's parents sued over the money and it was placed in a trust. A trial on the suit ended in a hung jury and the two sides settled, with Mead getting 15 percent of the money and the parents getting the rest.

The Salt Lake County District Attorney's Office filed criminal charges against Mead after the civil trial ended. At a preliminary hearing, Stormy Dawn Dunn Simon testified that Mead had talked about killing his wife during a 1992 telephone conversation.

Pamela Mead overheard that call and left her husband to live with her parents in Colorado. She returned to Mead because, her family said, he is a good actor and manipulator.

"Her only crime was being naive," Stokes told Mead at the hearing. "She loved you despite the lies, deceit and infidelity."

Twitter: @PamelaMansonSLC