This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

What is Salt Lake City Mayor Jackie Biskupski's new plan for emergency overflow winter homeless shelters?

Same as the old plan — minus one shelter and a yet-to-be launched study.

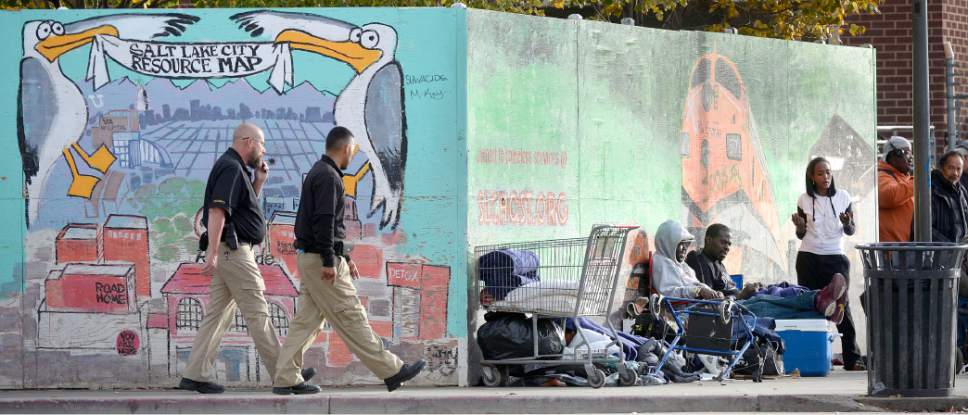

Heading into the cold season this year, there are, according to unscientific estimates, more homeless people camping out in Salt Lake City and the surrounding area than in previous years.

The Volunteers of America (VOA) outreach team is seeing more campsites and more campers, said Sandra Hollins, manager of the agency's outreach program. After the implementation of Operation Diversion on 500 West — which sought to guide homeless addicts into treatment and put drug dealers in jail — campers have spread out across the valley, Hollins said. They are camped along the Jordan River, in the foothills above Beck Street, in City Creek Canyon, in Fairmont Park in Sugar House, and in nooks and crannies throughout the area.

Each year between October and January, The Road Home's downtown shelter on Rio Grande Street sees a jump in clientele as many campers seek relief from the cold.

This month, however, the shelter is already creeping toward its capacity of 1,100. The Road Home's Midvale shelter, which had served as a winter-overflow option, has been transformed into a year-round family facility. It is presently at its limit of 300.

When it was available as an overflow shelter, it could house 75.

Some observers see a rising tide of homelessness that could spell trouble come December. For some on the streets, winter weather could be life threatening.

In September, the City Council discussed opening temporary winter shelters at existing but unused structures, such as the old Deseret Industries building in Sugar House. That general proposal was made public and was — at least informally — passed onto the Biskupski administration. The council requested a winter homeless plan from the mayor by Oct. 25.

But some council members were caught off guard last week when David Litvack, the mayor's deputy chief of staff, presented Biskupski's plan that put forth no new facilities.

Biskupski spokesman Matthew Rojas said Friday the administration did not want to "set precedent" by recommending new temporary shelters.

The mayor's overflow-shelter strategy is to use the St. Vincent de Paul dining hall, across from the Rio Grande Street shelter. It has been enlisted for that purpose every winter for many years and accepts only men in its overflow capacity.

Last year, the soup kitchen took in as many as 80 men per night who slept on mats on the floor, said Danielle Stamos of Catholic Community Services, which owns and operates the facility.

The mayor's plan, unveiled recently, would expand that to 150 people per night, which Stamos said is physically possible.

But Salt Lake City Fire Marshal Ryan Mellor noted that the official occupancy limit of St. Vincent de Paul is 80 people. It may be possible to raise that number, he said, depending on the sleeping plan, which he has not seen.

"It could go up," Mellor said. "But I'm not sure it could go to 150."

Late Friday, Rojas said the mayor, after discussions with the fire marshal, had amended the plan down to 80 people at St. Vincent de Paul.

Biskupski's plan also would seek a head count and "needs assessment" of campers downtown in conjunction with Salt Lake County's Collective Impact initiative. Such a study would provide data on whether more shelter space was needed this winter. The assessment would be restricted to the area around Rio Grande Street, said Alyson Heyrend, spokeswoman for Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams. As such, it would not seek data from other areas where campers are now found.

No date has been set for the assessment, Heyrend said, but it must be soon.

Biskupski's winter plan does not bring much comfort to City Councilwoman Erin Mendenhall.

"When we have people dying ... it's beyond numbers," she told Litvack in a recent council work session. "This is a real situation. We have our head in the sand if we don't think there is a need."

Litvack said the mayor's overflow plan is based on discussions with officials from The Road Home and other services providers and should be sufficient. If the head count shows more space is necessary, Biskupski will seek help from other Wasatch Front communities.

To date, Midvale is the only other Salt Lake County municipality willing to accommodate a homeless shelter.

Beyond that, Mendenhall said by the time a needs assessment could be completed, it would be the dead of winter with little time to tackle the multifaceted task of opening a temporary shelter that must meet building codes, while providing services and security.

Rojas disputed that, saying the assessment could be completed quickly. The mayor's plan, he said, will be data-based and yield the best possible strategy.

"Nobody wants anyone to have to sleep out in the cold."

Some, however, choose to stay outdoors, Mendenhall said. Many campers, she noted, refuse to go to the Rio Grande Street shelter for a variety of reasons, including violence and drug dealing.

That's true for Karen Cardenas, 43, who has been homeless for three years.

"I won't go into the shelter," she said. "It's totally disgusting."

But Cardenas said she would go to a temporary facility away from Rio Grande Street, if such a place existed.

City Councilman Derek Kitchen, who is an advocate for more temporary shelters, also questioned the mayor's plan and wondered how the administration arrived at 150 overflow beds.

"They are just shooting from the hip," he said. "It's not good policymaking."