This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The permanent closure of PacifiCorp's once-productive Deer Creek coal mine is nearing completion, but the utility still must figure out what to do with the millions of gallons of metals-laced water backing up in the Emery County mine.

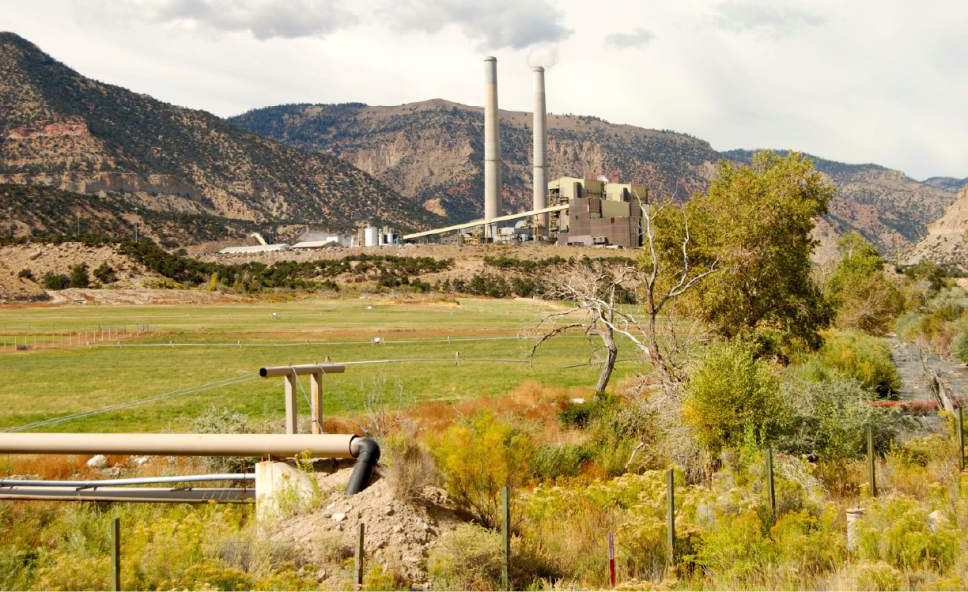

Currently, it is spending $500,000 a month in a complicated pumping and ventilating scheme while it seeks final go-ahead to build a 5.6-mile pipeline from a mine portal to unlined wastewater ponds at its coal-powered generating station, located where Huntington Creek emerges off the Wasatch Plateau.

PacifiCorp, the parent to Utah's largest utility, Rocky Mountain Power, developed the pipeline proposal after federal and state mine regulators, mindful of 2015's catastrophic Gold King Mine release, nixed an initial plan to plug the old mine with concrete bulkheads, thus entombing the water in the mine's extensive network of chambers and tunnels.

Now environmentalists are challenging the U.S. Forest Service's environmental review of the pipeline project, saying it didn't bother investigating what becomes of Deer Creek wastewater — about 315 million gallons in the first year — after it reaches the ponds.

PacifiCorp has been spraying some of this water onto a 245-acre "research farm" on the banks of Huntington Creek, a practice that HEAL Utah and other groups are deeply critical of.

HEAL's executive director, Matt Pacenza, says the utility processes its waste on the cheap instead of in accordance with industry standards.

The utility rejects this portrayal. In court filings in a related matter, PacifiCorp denies its wastewater practices at Huntington imperil the environment, affirming that it regularly collects relevant data under the watchful eye of the state Department of Environmental Quality.

In an unsuccessful effort to throw out a federal lawsuit from HEAL — which challenged the utility's practice of diverting runoff from Huntington's coal ash repositories to the very ponds that would accept the Deer Creek mine discharges — PacifiCorp spelled out the various steps it takes to safeguard water quality.

The plant operates 21 monitoring wells that are checked semi-annually for total dissolved solids, plus a number of specific contaminants, as well as pH, specific conductance, water level and temperature. Its permit also requires surface-water sampling at eight locations near the plant. Any exceedances of the permit's parameters must be promptly reported to the DEQ. The permit requires PacifiCorp to adhere to "best management practices" designed to minimize potential for degrading water resources.

The DEQ recently renewed that permit, but it requires the utility to phase out "land application" of wastewater onto the research farm within five years.

Pacenza contends the right way to deal with this contaminated water would be to store it in lined ponds and treat it.

"We have seen a pattern of the federal and state regulators just trusting Rocky Mountain Power to dispose of a tremendous amount of ash and contaminated water without much oversight. This utility is doing some pretty troubling things," said Pacenza, who is joined by Sierra Club and Western Resource Advocates in challenging PacifiCorp's wastewater practices. "It's not even a plan, it's half a plan. They want to pipe the water to a power plant, but they don't know what they will do then. It is a haphazard plan that deserves a second look. We don't even have data on what's in that water."

Deer Creek shuttered two years ago after a 40-year run and all its equipment has since been removed. But the closure has been anything but smooth, and the utility has spent at least $60 million so far.

The key issue has been the groundwater rising to the portals, bringing up traces of iron with it. PacifiCorp has sealed most of the portals, leaving open the ones in Rilda Canyon on the Manti-La Sal National Forest. The utility had hoped to pipe the water across the mine for discharge off the national forest into Deer Creek, but the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration vetoed that plan as well. Since the Forest Service would not allow this water to run down Rilda Creek into Huntington Creek, PacifiCorp now has no choice but to convey it by pipeline to the retention pond.

A 10-inch pipeline on a 12-foot-wide right-of-way is needed to handle 600 gallons a minute, a flow that would shrink to 200 gallons over the next decade. The gravity-fed buried line would run down Rilda along a Forest Service road, then along State Route 31 to the pond, resulting in a surface disturbance totaling just 12 acres on public lands, according to the Forest Service's environmental assessment.

The project "would not adversely affect water quality in the long term, nor contribute to the existing impairments," Forest Supervisor Brian Mark Pentecost concluded in his record of decision.

But environmentalists believe officials have unreasonably zeroed in on the earth-disturbing activities.

"The proposed project will simply move the pollution discharge from the Rilda Portal [on federal lands] to further downstream at the Huntington Power Plant [on private land]," the groups wrote in a formal protest. "The 'farms' the wastewater is currently sprayed on are not designed to yield crops; instead they are designed to absorb pollution that PacifiCorp would otherwise have to pay to treat. The current crops from the 'research farms' are not fed to livestock, instead they are disposed of at the Huntington coal ash landfill."

The groups insist on an analysis of the of the pond, which has a history of seepage into Huntington Creek, which is also already impaired due to dissolved solids, pH, temperatures and dissolved oxygen, the groups complain.

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713. Twitter: @brianmaffly