This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

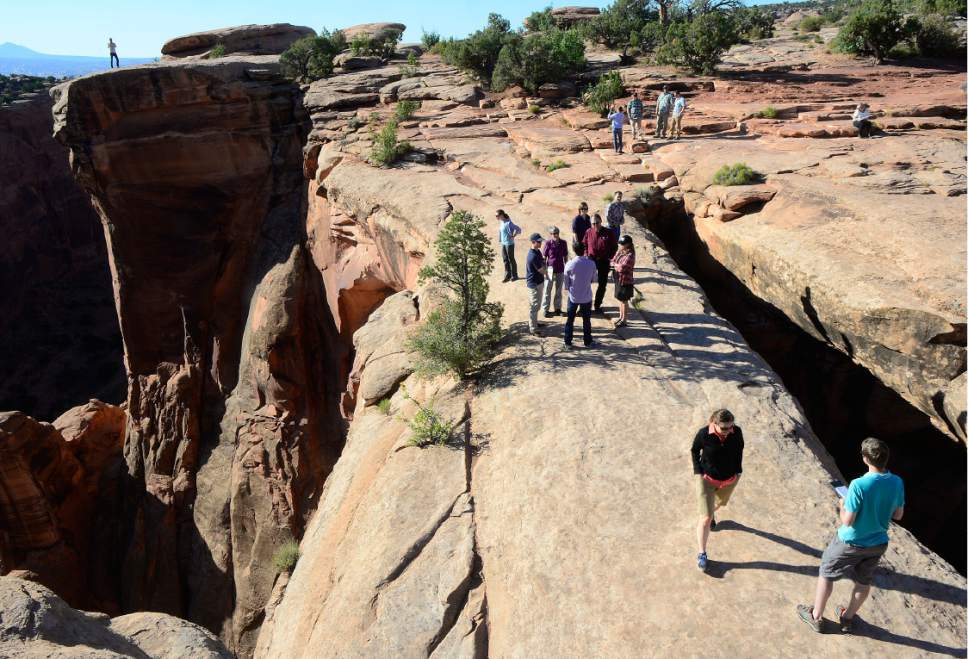

Federal land managers this week released Utah's inaugural master leasing plan for public lands around Moab. An effort to balance energy development with outdoor recreation in areas where scenic topography and minerals overlap, the Moab plan is one of 17 "MLPs" under development around the West.

In the works for the past four years, the plan guides future leasing on 785,000 publicly owned acres north and east of Arches and Canyonlands national parks.

Seen as a template for the other MLPs, it won plaudits from Utah's outdoor operators and conservationists, who argued it is about time tourism-dependent businesses had a more prominent say in how public lands are managed, and that master planning will curtail post-leasing conflicts.

But state officials and industry complained that MLPs in general add unnecessary layers of regulatory red tape and analysis over oil and gas development. The Moab MLP in particular errs on the side of too many restrictions on energy.

"It is moving BLM away from productive multiple use of public land to preservation only. The MLP is not supported by law and it will continue to stifle jobs and economic opportunities in Utah," said Kathleen Sgamma, president of Western Energy Alliance.

Her industry trade group was joined by a potash developer, Utah Gov. Gary Herbert, the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) and San Juan County in filing formal protests, all of them dismissed by the BLM.

"Implementing this plan will create more certainty for mineral development, contribute to the vitality of the area's recreation economy and maintain the incredible quality of life enjoyed by local communities," said Ed Roberson, the BLM's state director.

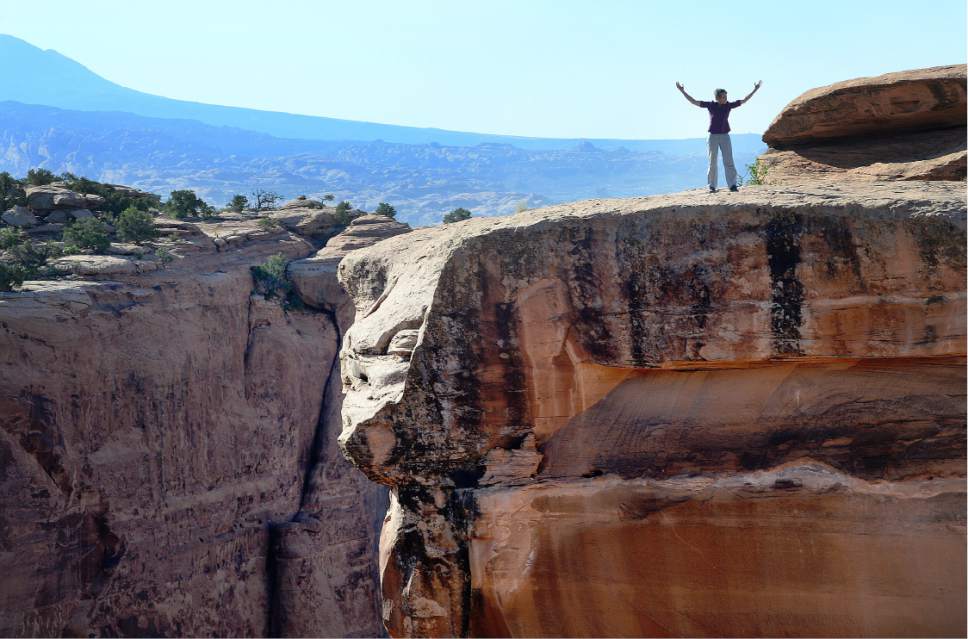

The plan "strategically" closes 145,000 acres within viewsheds of the parks to future leasing, covering hotspots such as the Porcupine Rim and Klondike trails, and restricts surface disturbance on another 306,000 acres in areas valued for their scenery and recreation, such as Moab Rim Trail, Corona Arch, Indian Creek, Lockhart Basin and Gemini Bridges.

Praise for the plan came from businesses catering to cycling, rafting and other outdoor pursuits, sportsmen, wildlife advocates and environmentalists.

Conservationists called the planning process "the gold standard" for how to conduct energy development on landscapes cherished for scenery and recreation.

"Energy development on public lands does not have to come at the expense of protecting our national parks," said David Nimkin of the National Parks Conservation Association.

The "comprehensive process" behind the plan made it clear, he said, that Moab's citizens and business support protecting Arches and Canyonlands. " Had oil and gas interests been given unrestrained access to lands adjacent to these parks, it would have had a massive impact on park visitors' wilderness experience and the quality of their air and water."

Former Moab City Councilwoman Kristin Peterson said the plan will safeguard her town's $263 million tourism economy. More than 2 million people visit the planning area each year.

"I am proud to know that going forward we will be taking a landscape-level and balanced approached to land management here in Moab so we can preserve these special places for generations to come," said Peterson, owner of the guide service Rim Tours. "This gives me confidence our recreation economy can continue to provide both jobs for locals and unique experiences for our visitors."

Also this week, the BLM released four alternatives for its San Rafael Desert MLP, covering 524,854 acres to the west of Canyonlands, covering parts of Wayne and Emery counties.

The Moab plan does not affect lands that are already under lease — about a third of the area, totaling 228,00 acres. Nor does the plan impose restrictions on 161,000 acres of state trust, private and split-estate lands within the planning area, although officials say the plan's restrictions could effectively eliminate development on these non-federal lands.

"If sufficient BLM lands are not available for oil and gas development in a particular area to constitute a viable economic unit, the in-held state trust lands will be rendered undevelopable," wrote LaVonne Garrison, SITLA's minerals director, in that agency's protest.

Gov. Gary Herbert's office claimed the plan conflicts with the San Juan County Energy Zone, established by the Legislature in 2015, which prioritizes "efficient and responsible development of energy and mineral resources" for much of the county.

In its own protest, the county said the plan violates federal law for failing to support commerce and economic development and multiple use of public lands.

The protests also claimed the plan negates the effort that went into revising the resource management plan for the Moab area. The BLM finalized this revision and revisions to five other Utah resource management plans during the waning weeks of President George W. Bush's administration in late 2008, triggering controversy and litigation that persists to this day.

The BLM said minerals covered with "no surface occupancy" stipulations can be accessed through horizontal drilling and flexibility built into the plan, which could allow for exemptions if drilling can be done in ways that don't degrade an area's scenery. However, the state argued the BLM overestimated the reach of directional drilling in this area's complicated geology and underestimated the per-well cost to drill.

The state was also incensed with the BLM's decision to segregate of potash and energy leasing. It would be appropriate, perhaps even more responsible, to extract these two resources from the same tracts, but the plan would make that impossible.

Brian Maffly covers public lands for The Salt Lake Tribune. Brian Maffly can be reached at bmaffly@sltrib.com or 801-257-8713. Twitter: @brianmaffly