This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A few hours before the Cougars of Brigham Young University took on the Mississippi State Bulldogs earlier this fall, team buses waited outside an Orem hotel, and large men in blue and white swarmed the lobby.

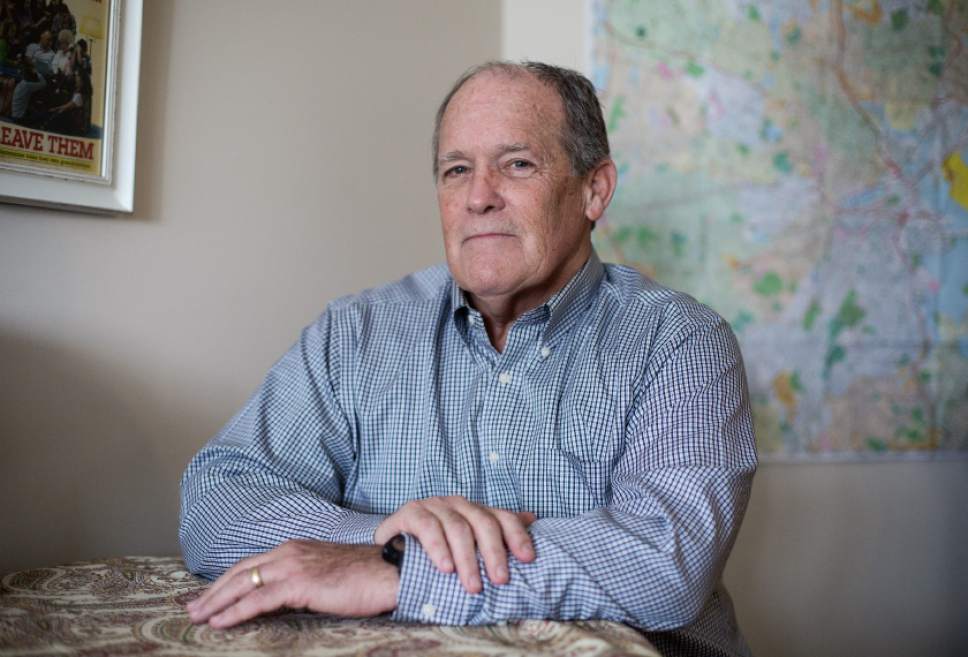

The scene would have excited most alums, especially a former player, but it worried Larry Carr. Nevermind that few if any of the players or coaches would have recognized the linebacker who helped lead BYU to its first-ever bowl game in 1974, the 64-year-old California man has been feeling paranoid — and a host of other disconcerting emotions — more and more these days.

He thinks he knows what is to blame.

That's another reason he preferred to avoid the crowd.

"I knew that as soon as my name came out with this that it would be mud," Carr said in the privacy of his hotel room. "I would go from the little-known, undersized [Cougar] Hall of Fame linebacker to the football player who sued BYU. I knew that wouldn't go over well in a lot of places, so that was really hard for me. At the same time, I felt that I couldn't not. It was really important."

Carr is one of dozens of former college football players suffering concussion-related symptoms who have filed lawsuits in recent months against their alma maters, their former athletic conferences and the NCAA. The former players, represented by Chicago and San Francisco attorneys at Edelson PC, include former University of Utah lineman Richard Seals, who played for the Utes between 1995 and 1999.

Carr's suit asserts BYU, the WAC and the NCAA "kept their players and the public in the dark about an epidemic that was slowly killing their athletes."

BYU did not respond to a request for comment. The NCAA, meanwhile, has derided the lawsuits in the past, saying earlier this year that myriad claims were an effort to interfere with a settlement in a 2011 lawsuit involving the NCAA's handling of concussions.

Some of Carr's own acquaintances have called the lawsuit, which seeks $5 million in damages, an attempted money grab.

The former linebacker sees it as a quest for justice and an attempt to help others avoid a similar fate.

During his playing days, Carr was a hard-hitting middle linebacker, a three-year starter and a team captain for the Cougars. He holds the school record for averaging 12 tackles per game for his career and is third all-time in tackles at the school, recording 389 in three seasons. His lawsuit alleges he was "subjected to approximately 2,000 to 3,000 violent hits to his head during hitting drills, practice and games."

"I can remember all the time being on the field and asking teammates to help me read the signals," Carr said. "… I would watch film the next week and not have any recollection of what had happened."

His wife, Laurie Carr, remembers standing by his side as he came out of the field house in Provo, dazed from concussions. Now, Laurie Carr said, she is standing by his side as he suffers the consequences of those hits.

After playing professional football in Canada for a year and a half following graduation, Carr went on to become a professor at Oakland University in Michigan, before leaving to start his own business and then, later to become a teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District. This year, he retired some eight years earlier than he once planned, due to mounting issues he and his family fear are related to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Laurie Carr said she first suspected something was wrong years ago, when her husband began having trouble retrieving words. Since then, Larry Carr has battled depression, paranoia, loss of short term memory and "unreasonable anxiety."

"He couldn't shop for shoes because there was a man standing behind him looking at shoes," Laurie Carr recalled of one instance. "He just had a meltdown in the store. We had to leave."

Carr's story is hardly unique, but how many others are living some version of his reality is unclear.

In October, a partnership of Veterans Affairs, Boston University and the Concussion Legacy Foundation announced that CTE had been found in players from more than 100 college football programs, and that 138 of the 152 brains of former college football players studied by the group had been diagnosed with the disease.

"The reality is there are an unknown number of former college football players who are developing CTE or have CTE and need help," said Chris Nowinski, CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. "And these schools have been making a ton of money off the game."

Legal experts, however, believe cases like Carr's will have difficulty succeeding in court.

"You would have to show that the organization did something it shouldn't have done … or that they didn't do something they should have done," said University of North Carolina law professor Barbara Osborne.

And while Carr's lawsuit argues BYU and others should have recognized the risks associated with concussions, Osborne believes they'll have a hard time proving it.

There is research on football concussions dating back to the 1950s. Carr's lawsuit cites a 1952 article in The New England Journal of Medicine that suggested a three-strike rule for football-related concussions.

"But there was absolutely no consensus within the medical community until much later that concussions were really something to be concerned about," Osborne said, "let alone having known or established protocols that all schools should be following."

She added, "That's not to discount that people are suffering terrible consequences from having had multiple concussions, but that doesn't mean the NCAA as an organization is liable."

Fearing what problems await, Carr and his wife pushed up their plans to serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

"Let's do what we can do while we can still do it," Laurie Carr said.

So Larry Carr retired early. He then sued the school that celebrated him as part of its 2010 Hall of Fame class.

"I'm not saying BYU is evil," he said. "But they need a kick in the butt. They need to move forward — and not just BYU, all of the NCAA."

Carr wants universities and the NCAA to provide long-term care and insurance for former players. He also wants to see partnerships between athletics departments and university researchers, with the hope of keeping future players safe.

"The biggest brains are at the universities. There should be action," he said. " … But institutions that rely on millions of dollars from football aren't interested in addressing this."

What he does not want, he said, is for football to go away, though even he is conflicted about the game. He still watches college football on Saturdays and his son coaches the game in California.

"On one hand, we love football, we worship football," Carr said. "But, on the other hand, how can a moral people worship a sport that is killing people? We worship a game that is destroying people's minds and families."

That uncertainty has led Carr here.

"I don't know what's going to happen," he said. "In 10 years, am I going to be in a home? Am I going to forget my family? I don't know what's going to happen. So I need to talk about this. I need to be taken seriously."

His lawsuit, filed in Colorado District Court in August, is in the early stages of the legal system, and it may still be when the Carrs finish their Mormon mission in Boston. There, they work in a courthouse, recording birth, marriage and death certificates for the church's genealogy research.

And there Larry Carr also finds a moment for himself.

"I get up every day," he said, "and pray that I'll find peace."

Twitter: @aaronfalk