This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In 1972, during LaVell Edwards' first season as BYU's football coach, Arizona State brought a Top 20 team to Provo in mid-October. Even with ideal weather and an attractive opponent, a crowd of only about 23,000 occupied two-thirds of the venue then known as Cougar Stadium.

You have to understand, that Saturday marked the opening day of the Deer Hunt.

This, then, is Edwards' legacy: He made hunting season inconsequential in Utah.

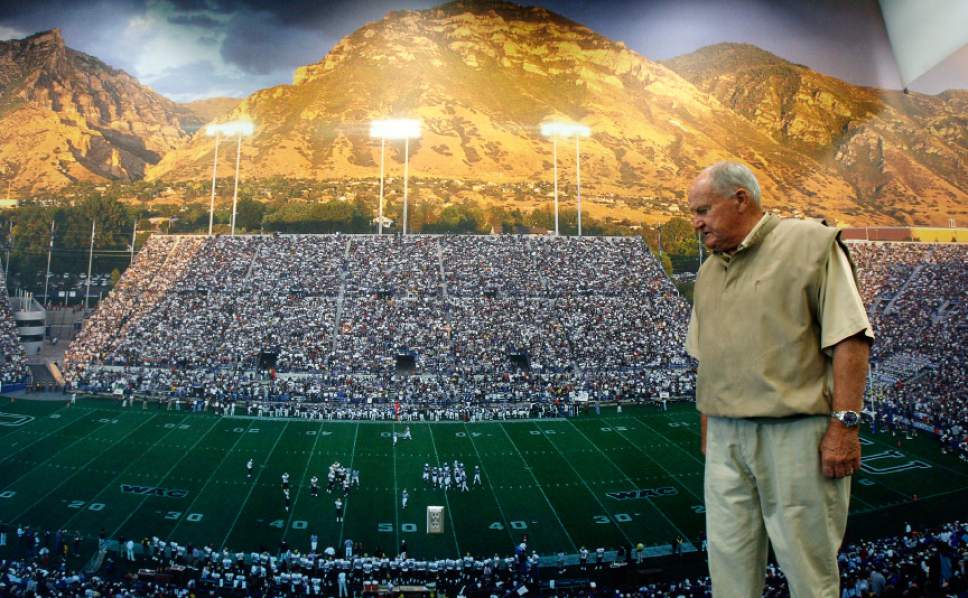

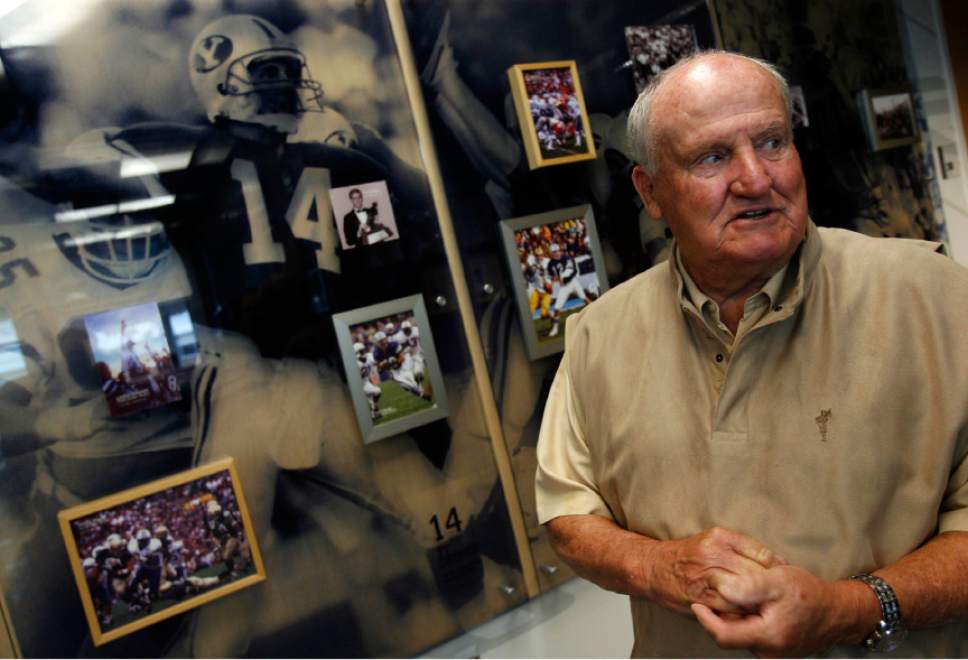

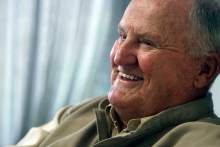

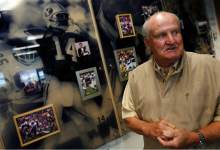

Edwards died at age 86, having reshaped athletics on the BYU campus and driven changes throughout college football with an offensive scheme that he boldly authorized, even if he didn't invent it. The sport was merely a diversion before basketball season in Provo before Edwards took over the program and the Cougars started filling the air with footballs and filling a stadium that would be expanded and now bears his name.

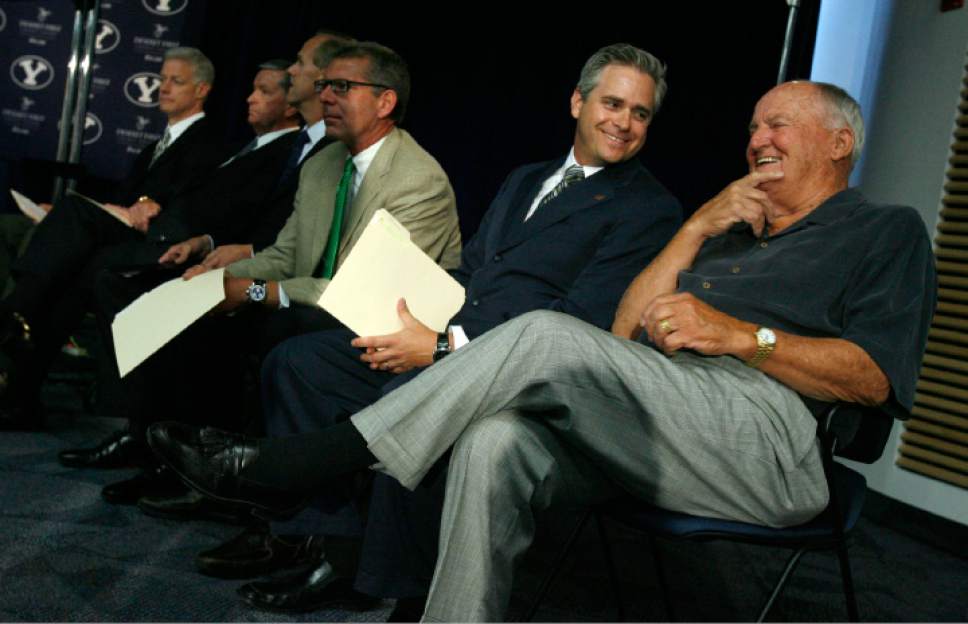

The way Edwards treated people, making them feel more important than he was, further distinguishes him among Utahns. Even with his credentials, he never outgrew his background as a product of Orem and Utah State.

Saying that Edwards' greatest strength as a coach was staying out of the way would be only a slight exaggeration. He hired assistants such as Doug Scovil, Ted Tollner, Mike Holmgren and Norm Chow and allowed them to operate the offense, while creating the framework of a program that was built to last.

The Tribune launched our annual rankings of the Most Influential People in Utah Sports after Edwards retired in 2000. On an all-time basis, he might be No. 1.

The status that college football enjoys in this state is traced directly to Edwards' work at BYU, where the Cougars stood 5-37-4 against the University of Utah when he was promoted. The Utes eventually responded, rebuilding themselves into a Pac-12 program after Edwards reversed those decades of Utah's dominance.

Beyond our borders, Edwards' approach to offensive football influenced coaches around the country. Not all of the the X's and O's came from BYU's playbook, the overall philosophy has taken hold everywhere you look.

And it all stemmed from Edwards' defensive background — which is either completely understandable or totally illogical.

He always labeled his approach an act of desperation, because nothing else really had worked in 50 years of BYU football. What's impressive, looking back, is how Edwards stuck with the offense — during both the initial tough times and the highly successful years that followed.

After turning to the passing scheme in his second season of 1973, Edwards went 5-6 and then started 0-3-1 the next season. The Cougars kept throwing, winning a Western Athletic Conference championship in '74.

They didn't stop there. After the program's success enabled BYU to recruit better athletes, Edwards once said, he "resisted the temptation to become conservative."

Such commitment to the passing game, as detailed in a recent book about offensive expert Hal Mumme, is the reason the Cougars kept winning and creating a national following among coaches such as West Virginia's Dana Holgorsen and Washington State's Mike Leach. Mumme learned that "to play like BYU, you had to fully dedicate yourself to the pass, to be better at it than anyone else."

In "Perfect Pass," author S.C. Gwynne writes, "Hal also loved the Cougars' arrogance, the belief among the players that they could not be stopped."

That's true. Yet the program's patriarch remained humble, always crediting others for his success. Everyone who knew him has a story of Edwards' influence. I've lived in Utah for 46 years, worked for four newspapers in the state for nearly that long and remained Lutheran in the process — all because of LaVell Edwards. He had a gift for guiding people and yet allowing them to be themselves.

My father, Dave Kragthorpe, played football with Edwards at Utah State and joined him on Tommy Hudspeth's BYU coaching staff in 1970, after I'd lived in three other states by age 9. After Edwards became the head coach in '72, we stayed in Provo eight more years. That's remarkable, in the coaching profession.

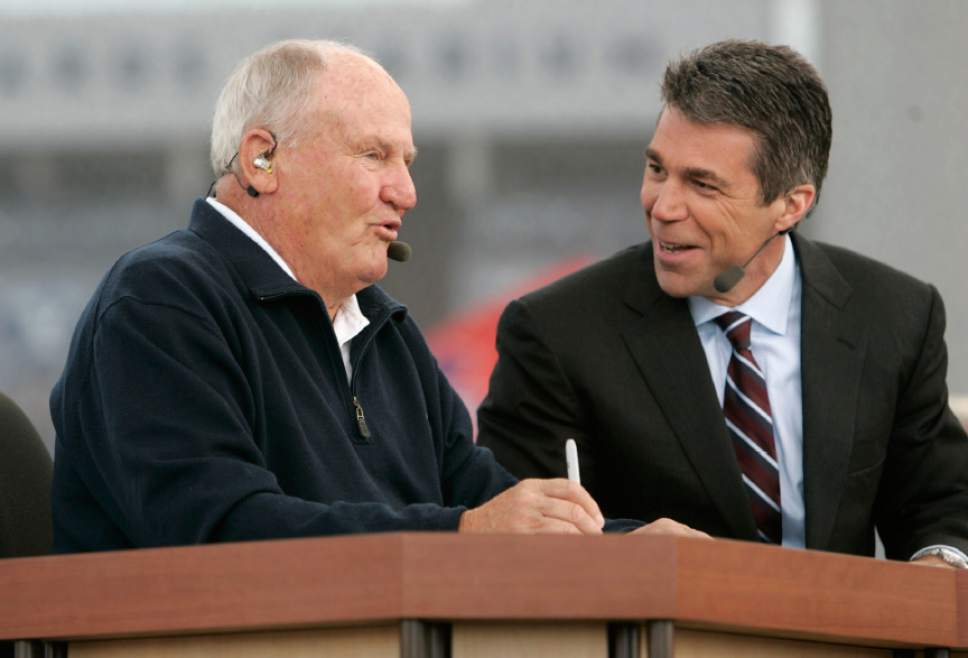

My introduction to the media business came on a snowy day in '73, when I asked Edwards if I could join him in the radio booth of Utah's stadium for his postgame show. In this era, no coach's kid ever would pursue sportswriting, but Edwards' relationship with the media made it seem like a natural connection.

The irony is that after The Tribune hired me to cover the BYU beat in 1990, some self-study shows that I probably wrote more critically about Edwards' program in those three years than I have about any college or pro team since then. That's because I knew he conditioned himself to withstand the scrutiny, and he understood my job description.

That was LaVell Edwards, to the end. Just as in my dad's experience of coaching BYU's offensive line, I felt authorized to cover the Cougars thoroughly, by a man whose greatest impact stemmed from giving someone a job and letting him do it.

Twitter: @tribkurt