This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A few miles from Bluff • A 20-minute walk from an unmarked trailhead on Butler Wash Road sits one of many ancient dwellings in the small canyons that wind through the vertebra of the spine-like Comb Ridge.

Ancestral Puebloans once stood atop this structure and pressed painted hands against the inverted sandstone wall, leaving prints in red, yellow and white.

Lower down are the tracks of a prized domesticated turkey, and nearby corn cobs may predate the Magna Carta. A kiva's stone walls still bear a log that propped up its roof as many as 900 years ago, while its plaster interior reveals the faint imprint of woven sandals.

All around is evidence that people once lived and even thrived off this unforgiving landscape.

And there's evidence of modern life, too.

Dozens of the remaining pottery shards have been piled together for display.

A game of tic-tac-toe is scratched a few paces from the handprints, and stone surfaces have been blemished by the sharp metal ends of trekking poles.

An entire wall was toppled in late 2014 or early 2015, perhaps backed into by a wandering cow.

This and hundreds of similar sites in the region illustrate what Native American and environmental groups have sought for years to protect.

But while proponents celebrated President Barack Obama's designation of 1.35 million acres of southeastern Utah as Bears Ears National Monument — marking it off-limits to oil and gas developers — they acknowledge immense challenges to come.

Its new label may attract more uninformed visitors to a delicate region Obama's proclamation lauds as "one of the most intact and least roaded areas in the contiguous United States," with "that rare and arresting quality of deafening silence."

Meanwhile, Utah's congressional delegation has threatened to cinch the region's federal purse strings, and many San Juan County residents believe the monument is a threat to rural Americans.

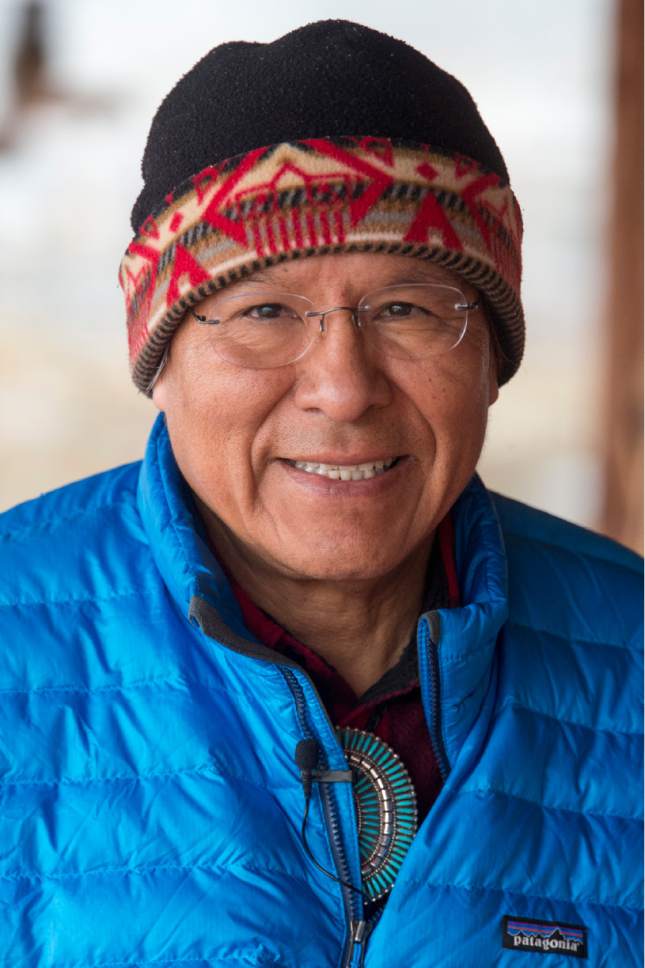

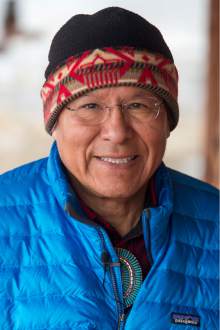

Said Utah Dine Bikeyah board member Mark Maryboy: "I see it as a humongous, tremendous amount of work that has to take place."

—

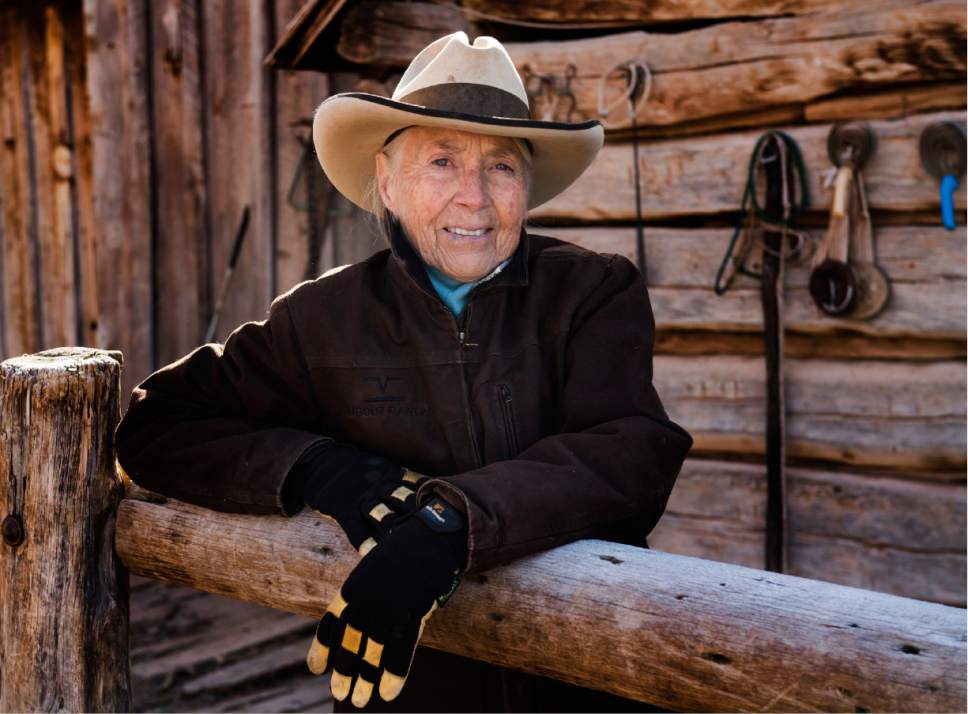

Rancher Heidi Redd was 25 when she drove up a dirt road to her new home in Indian Creek.

Two years earlier, President Lyndon B. Johnson had signed into law Canyonlands National Park, and there was talk even then of "completing" the park by extending its boundaries eastward to Newspaper Rock. But that never materialized. Redd had the remarkable place to herself.

"When you cowboy year after year where you don't see people, you get the feeling that all these lands you're running cattle on belong to you," Redd said.

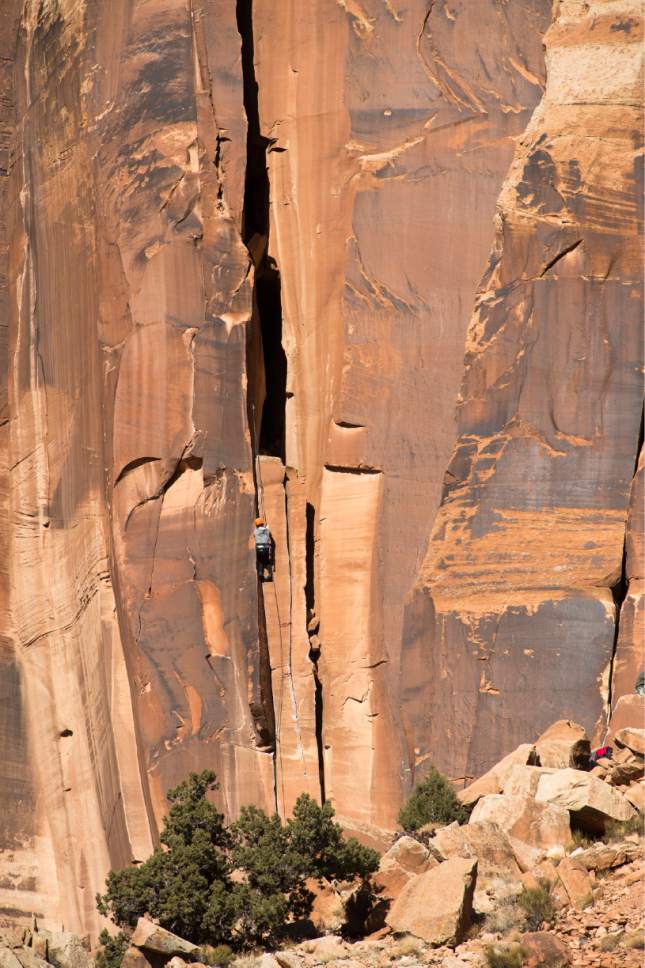

Redd said her "wake-up call" came in the early 1990s. As tourists flocked to Moab for slickrock mountain biking, climbing magazines began to highlight Indian Creek's abundance of world-class cracks.

Climbers trespassed to access the sheer Sundial face — in their lingo, the Paragon Prow — behind Redd's house. To the west, they scaled the clifftop spires of what she calls the Moki Family, with which Redd feels a spiritual attachment and where she hopes to have her ashes spread. A parking lot just down the now-paved State Route 211 hosts climbers year-round.

Out on the range she and her cowboys began to encounter ATVs. Drivers would weave through and scatter her herds instead of waiting for the cattle to amble by.

Still, Redd said, all involved eventually learned to treat one another with more respect.

In 1997, she and her ex-husband rejected wealthy investors to sell their private acreage to the Nature Conservancy, which now leases the ranch to Redd.

Although Redd, 75, has formally retired from ranching, she continued to advocate for the land's preservation while on San Juan County's public lands council and last year tried unsuccessfully to unseat state Sen. David Hinkins. Her son Matt runs her cattle on some 275,000 acres of public land that all falls within monument boundaries.

Redd said the monument designation does nothing to limit access to current users. But having already seen one boom, she does fear more traffic and infrastructure.

"When I look at the beauty here, I think, 'Oh, please, not another parking lot that detracts from the natural beauty,' " Redd said.

Interior Secretary Sally Jewell was told repeatedly during her four-day visit in July that the internet had already overexposed the area. Bears Ears needed protection, monument proponents said. Not more buildings, or larger crowds.

Jennifer Davila moved to Bluff some 33 years ago as the daughter of river guides and now owns a boutique hotel near the town's distinctive Navajo Twins formation. Her business' bottom line aside, she said, she dreads the thought of Bluff becoming a "new Moab."

"I've grown up playing in these lands," Davila said, where "you can go out and get lost."

—

Josh Ewing and his wife found themselves on the west side of the Cedar Mesa during a 2001 road trip, after driving the scenic Burr Trail and taking a ferry across Lake Powell.

Right next to the road, they saw a ruin that wasn't in any guidebook Ewing knew of. The sun rose the next morning to reveal Arch Canyon. They were entranced.

"I got back to Salt Lake and I was like, 'Where were we?' "

He returned a few times each year for 13 years before quitting his corporate job and moving to Bluff, where he became executive director of Friends of Cedar Mesa, a nonprofit conservation group.

"Every one of our supporters has a story like that," Ewing said. "Hiking in other places gets boring."

That the area has few developed trails or interpretive signs is part of its charm for explorers, few in number until the rise of GPS and Google: The scarcity of information fuels imagination and cultivates a sense of discovery.

But it also leaves some visitors ill-prepared to stumble upon archaeological sites that require a strict interpretation of the Leave No Trace ethic.

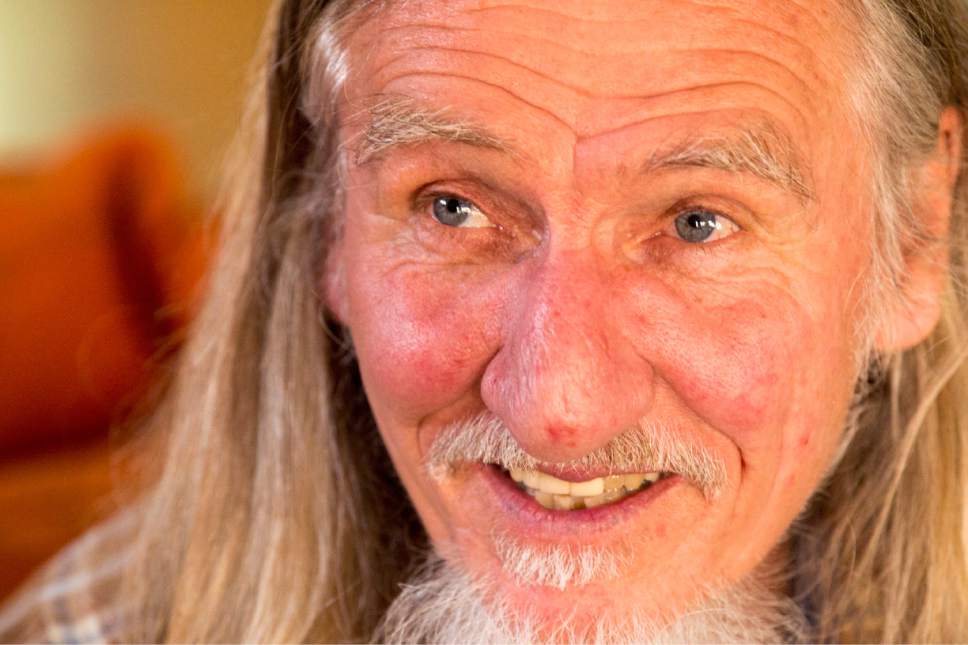

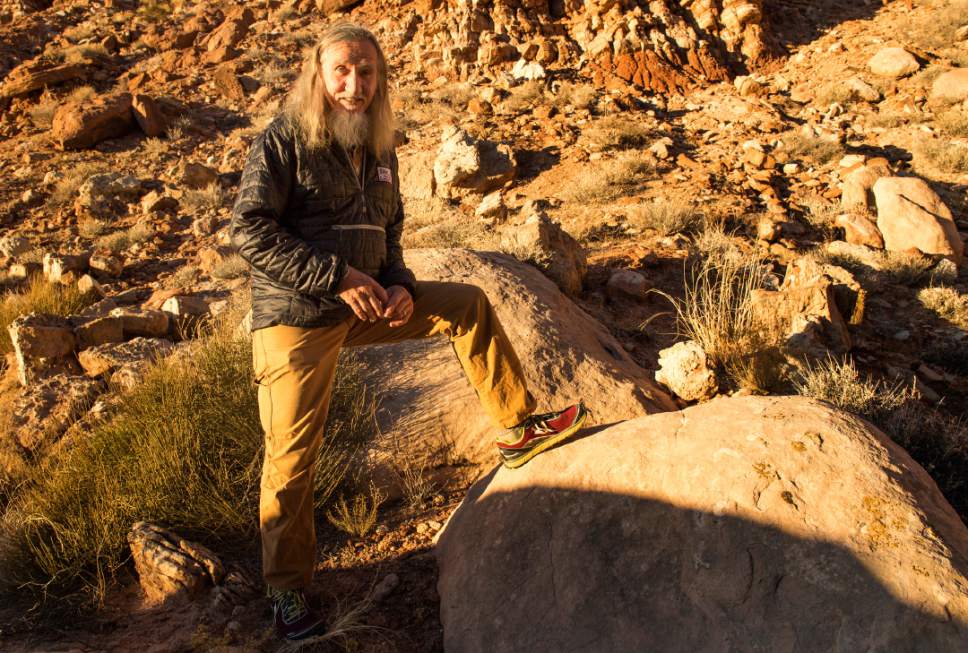

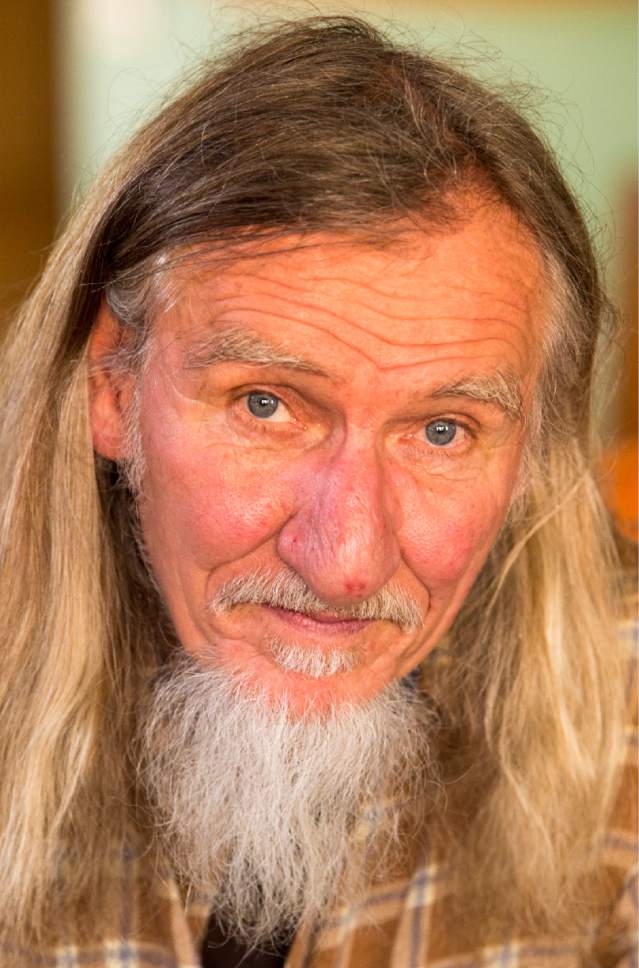

Bluff's Vaughn Hadenfeldt, Friends of Cedar Mesa board chair and owner of Far Out Expeditions, recalled that when he was documenting the 1894 Richard Wetherill expedition in the Grand Gulch, lead-soldered cans kept disappearing from Wetherill's campsites.

Backpackers, thinking them litter, were carrying them off to the Dumpster.

Ewing showed Jewell in July where Native shrines had been depleted by hikers who picked off rocks to make cairns.

"Most people, they just don't understand that they're doing something wrong," said Hadenfeldt, who hands out rubber tips for exposed trekking poles when he's out in the backcountry. "People will typically do good if you give them reasons to be good."

Should tourists arrive by the busload to check "Bears Ears ruin" off their list of Utah wonders, some sites may simply need to be "sacrificed," said Hadenfeldt and Ewing.

For instance, a few ruin walls might be stabilized, and agencies might funnel traffic to already popular sites like the Wolfman Panel petroglyphs, near one of the first turn-ins on Butler Wash Road.

Hadenfeldt yearns for a coordinated information campaign. Now, he said, maps at the Bluff Fort Visitors Center identify places to find pottery shards, and front desk employees at some Bluff hotels are eager to share directions to their favorite spots.

"It's probably not a good idea," he said.

Hadenfeldt said the most needed educational resource is personnel. Two seasonal rangers patrol nearly 2 million acres from the Kane Gulch Ranger Station at the Grand Gulch trailhead.

Bureau of Land Management Director Neil Kornze acknowledged during Jewell's visit that staffing was insufficient, and the BLM has since awarded Friends of Cedar Mesa a matching grant to help protect the area.

But Kornze and Jewell will soon leave their posts. A new Republican administration is being called upon to undo Obama's work, and widespread opposition from the state's Republican leaders may imperil appropriations from a GOP-led Congress.

—

Maryboy, a former four-term San Juan County commissioner, still smarts from a comment made at a July public hearing by Commissioner Bruce Adams, who said his white ancestors were the first to properly settle the area.

Likewise, Maryboy said he's pained by Commissioner Rebecca Benally's insistence that Native Americans will no longer be allowed to gather herbs and wood in the monument, and, especially, by Commissioner Phil Lyman's May 2014 illegal ATV protest ride through Recapture Canyon.

"If I went to Blanding or Monticello and held an ATV tour through a cemetery, I probably would still be in prison right now," said Maryboy, who lives in Montezuma Creek and recalls when Navajo elders implored Democratic presidential contender Robert F. Kennedy to protect their sacred lands during a 1968 visit.

He and others in a tribal coalition tout Bears Ears as the first monument to be called for by Native Americans and to include them in its management, but they've been derided by leaders like Benally and state Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, as puppets of deep-pocketed environmental groups who simply hate rural industry.

Those sentiments were on display Thursday morning in Monticello as more than 200 people gathered on Main Street, their children carrying signs that called on the president-elect to "Trump this monument."

The debate is deep-seated and regionally drawn. As a young commissioner, Maryboy was often at odds with longtime county leader Cal Black, a Blanding uranium miner and founding Sagebrush rebel.

Davila said many Bluff children are branded outsiders when they attend San Juan High School in Blanding, and people in both towns boycott businesses they view as pro- or anti-monument.

Asked if monument proponents can do anything to earn buy-in from the more conservative Monticello and Blanding crowds, Davila said, "Nope."

Hadenfeldt said there are valid arguments against a monument — even if he lobbied hard for the designation. It may very well increase usage, he said. But he's weary of what he regards as unfounded talk about restricted ranching or ATV use, and frightened to see children who are told what to believe before they can make up their minds for themselves.

"It's tough living right here, knowing how much people living 25 miles away hate me, and how much they think their world is coming to an end."

Redd, who narrowly beat Hinkins in San Juan County, drove to Monticello and heard many of Thursday morning's speeches. She eventually left to get coffee. They were too repetitive, she said, and not focused on the real problems that lie ahead.

"Every citizen in San Juan County needs to now start the process of figuring how we deal and how we work with the monument. I think trying to fight it is just wasting time."

Twitter: @matthew_piper