This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When two police officers shot and critically injured a 17-year-old black boy outside of a Salt Lake City homeless shelter nearly a year ago, it sparked another round of angry protests.

"We're not going to let you keep killing us," said Lex Scott, addressing police at a Black Lives Matter rally in July, as she sported a pistol holstered with black straps around her right leg. The crowd of hundreds later chanted: "No justice, no peace, no racist police!"

Yet, the downtown shooting, which Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill deemed justified, also resulted in something else: the formation of the "community activist group," known as the CAG. Many of those very same protesters, so critical of police, have — at the request of Salt Lake City Police Chief Mike Brown — met with officers every other week for almost a year.

The idea was to have members of the police department listen to these frustrated residents and have these activists listen to the officers. Because, as Brown put it: "It's really hard to hate someone up close."

Former Salt Lake City Councilwoman Deeda Seed, who is among the activists, said community outrage over the February 2016 shooting of Abdullahi "Abdi" Mohamed "accelerated" talks about the need for better communication. The early gatherings were tense and the meetings continue to be frenetic, but they've built some trust through the structured conversations, something that simply didn't exist before.

"When we're yelling at each other from across the street, we're not being heard," Detective Greg Wilking said. "We're not hearing them. They're not hearing us."

While not completely satisfied, the CAG feels heard and has seen its advice result in some real changes.

Because of activist feedback, the police department added a button on its homepage for users to more easily submit complaints, and several photos of stoic-looking officers on the website have been swapped for photos in which they are smiling, Brown said.

The department also now publishes use-of-force data and statistics on its site, which includes information on age, gender, race and ethnicity of arrestees.

"It's huge to me, because when you work in civil rights, you're constantly told that it's all in your head — that profiling is in your head, that mass incarceration doesn't exist," Scott said. But she believes the data affirms her view.

Though only about 2.7 percent of Salt Lake City's population is black, about 11.7 percent of SLCPD use-of-force cases involve a black resident. Similarly, American Indians account for about 1.3 percent of the population, but account for about 5 percent of use-of-force cases.

White people, a demographic group that includes most Hispanics, make up about 73.4 percent of the population and are involved in about 76.9 percent of use-of-force cases.

Conversely, Asian and Pacific Islander people account for 7.9 percent of the population, but are only involved in 3.6 percent of use-of-force cases.

Police "have noticed" the numbers, Sgt. Brandon Shearer said, and are looking into why the use-of-force rate is so high among black people and Native Americans. He said one factor is that "crimes typically occur in neighborhoods that have a lower socioeconomic status, which a lot of our neighborhoods like that have an overrepresentation of minorities."

He said the department is trying to hire a more diverse police force. They've been working with Scott to focus on diversity in recruitment and new hires.

Issues of race and policing infuriate this aggressive activist.

"I yell at cops. I call them out. I fly to Ferguson, Mo., and yell in their face, you know. I fight hard," Scott said, but CAG meetings aren't a time to "just scream at the police for an hour."

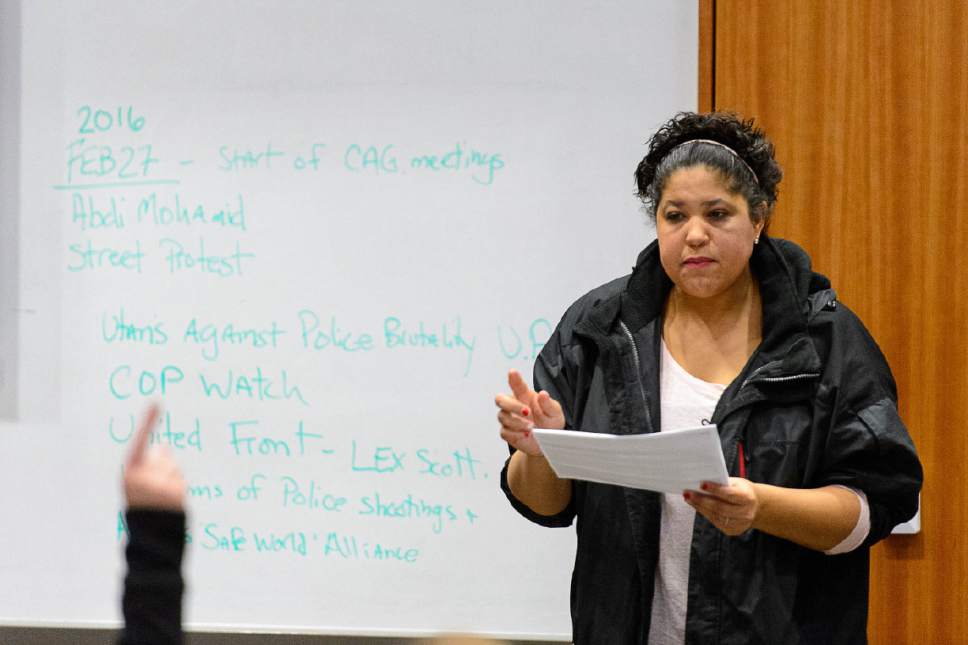

Members of the CAG have their own priorities. Before each meeting, the group chooses a topic from a list of issues and designates an activist to lead the discussion. The department brings in specialists in that area.

Among the two dozen activists who attended a Jan. 18 meeting, which was an overview of past discussions, were representatives of the United Front, Utah Against Police Brutality, Utahns for Peaceful Resolution, Cop Watch and Community Coalition for Police Reform; others merely described themselves as citizens or individual activists.

Some who attend have had friends or family members die as a result of lethal use of force by police, and meetings can get "emotional," Seed said.

Some activists remain skeptical of the role CAG has played in departmental changes.

Jacob Jensen, of Utah Against Police Brutality, says he believes in Brown's "sincerity to have one of the best police departments" and improve training, but "realistically," the chief "was already going to accomplish a lot of that stuff on his own."

"Like, if he didn't want to put any statistics up, there's no way the CAG would have persuaded him to do that," Jensen said, though he acknowledged the online complaint button was a "big win" for the group.

Brown said some plans were in place before the CAG meetings began — such as de-escalation training and a focus on community relationships — but the chief says activists' perspectives have "challenged some of our traditional thinking."

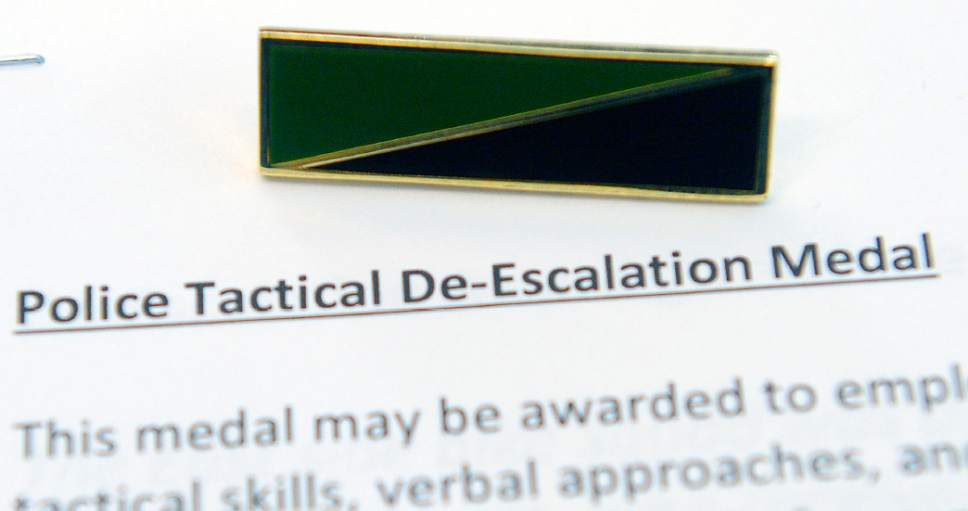

As an example, Brown created de-escalation medals for officers who resolve situations without use of deadly force, even though it could be justified. So far, 15 officers have been recognized, the chief announced at a CAG meeting.

Hearing the number "brought me to absolute tears because that is so powerful," Scott later told The Tribune. "To me, when I look at that, that's 15 lives that were saved."

While that announcement drew compliments and applause from the activists, Shearer said, "we've not crested the hill by any means," a nod to items the CAG still wants to address.

One recent issue involves the release of footage from body cameras worn by officers, specifically video depicting the Mohamed shooting. The footage was kept under wraps as prosecutors built a subsequent criminal case against the Somali refugee, who is accused of aggravated robbery and drug possession with an intent to distribute.

Prosecutors didn't want to release the footage, arguing that its release may jeopardize Mohamed's chance at a fair trial, though once the video was shown in a January preliminary hearing, the Salt Lake County District Attorney's Office decided to release it.

The police department has been working with the mayor's office to draft a new policy regarding bodycam footage, Brown said at a recent CAG meeting, but when Jensen asked for a copy, Brown said "please be patient."

The activists didn't want to be patient, which led to a small protest at the mayor's office. The following day, Mayor Jackie Biskupski handed over the draft policy, which calls for the release of bodycam video no more than six months after an officer-involved shooting.

County prosecutors don't like that policy, but CAG members have mixed feelings.

The policy "clearly is a compromise," Seed said, and is a "good step in the right direction," though six months is "a long time."

Mostly, she's glad about the conversation the topic is generating in the community, seeing it as another win for the CAG.

The dialogue stemming from these meetings provides a "big-picture look at how we can have the kind of law enforcement in the community that we want," Seed said.

"Believe it or not, we're making progress."

Twitter: @mnoblenews