This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A fixture in the organization working for children sexually abused by Catholic priests has resigned his post, an announcement that coincides with a lawsuit from a former employee alleging the group colluded with lawyers to refer clients and profit from settlements.

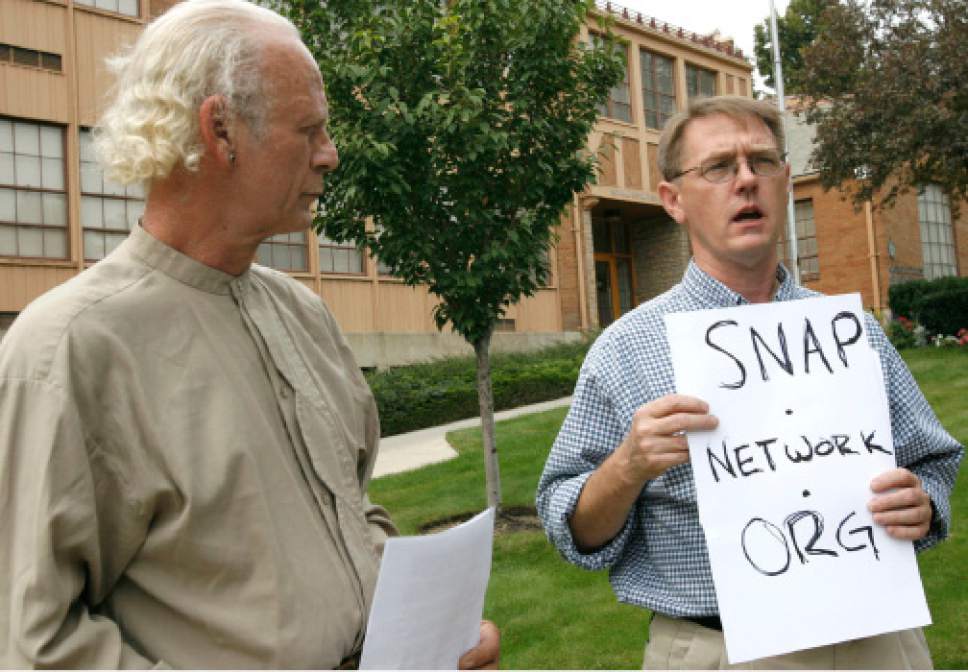

David Clohessy, longtime executive director of SNAP, or the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, said Tuesday that he left in December and his departure had nothing to do with the lawsuit, which was filed in Illinois on Jan. 17.

"Not at all," Clohessy said by phone from his home in St. Louis, where SNAP has its main office. "My last day was five weeks ago, before this lawsuit ever happened."

The lawsuit by Gretchen Rachel Hammond names Clohessy and other SNAP leaders as defendants and alleges that "SNAP does not focus on protecting or helping survivors — it exploits them."

The group, which more than any other is responsible for revealing the scandals that have continued to rock Catholicism in the U.S. and around the world, "routinely accepts financial kickbacks from attorneys in the form of 'donations,' " Hammond alleges.

"In exchange for the kickbacks, SNAP refers survivors as potential clients to attorneys, who then file lawsuits on behalf of the survivors against the Catholic Church. These cases often settle, to the financial benefit of the attorneys and, at times, to the financial benefit of SNAP, which has received direct payments from survivors' settlements."

Hammond, who worked on fundraising for SNAP from 2011 until 2013, said she feared reprisals from SNAP leaders over her objections to the lawyers' payments and suffered serious health problems as a result. She said she was fired in 2013, allegedly because she confronted her bosses over their practices with victims' attorneys and that the dismissal has hurt her career.

The lawsuit was first reported by National Catholic Reporter.

It long has been assumed that SNAP received substantial donations from some of the high-profile attorneys who specialize in these cases and who have won multimillion-dollar settlements from the Catholic Church in the U.S. and its insurance companies.

But Hammond's filing shows how critical such donations are to SNAP's survival: It asserts, for example, that 81 percent of the $437,407 in donations SNAP received in 2007 came from victims' lawyers, and 65 percent of the $753,596 it raised in 2008 came from attorneys.

More problematic is Hammond's allegation that SNAP worked hand in glove with victims' attorneys and received "direct payments from survivors' settlements."

"The allegation is explosive because it's unethical," Jeff Anderson, a prominent Minnesota attorney who has represented victims of clergy sex abuse, told the Chicago Tribune.

"I've never done it nor would I ever do it," said Anderson, who added that he regularly donates to SNAP but not in exchange for referrals.

In a statement, SNAP President Barbara Blaine, who founded the group along with Clohessy, said the allegations "are not true."

"This will be proven in court," Blaine said. "SNAP leaders are now, and always have been, devoted to following the SNAP mission: to help victims heal and to prevent further sexual abuse."

Clohessy would not comment to Religion News Service on the lawsuit, but he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the charges were "utterly preposterous." And he told RNS that SNAP "didn't have any clue at all" that it was coming.

"We've heard nothing from her for four years since she quit. So that caught everybody by surprise.

"We have always been under attack by somebody at some point, legally and otherwise," Clohessy added. "So it's never been a factor in any decision making, at least not for me certainly."

Asked why his departure was not announced until after the lawsuit was filed, Clohessy said it was only because there were "just a lot of details to extricate myself from everything after 30-something years. Just working out details with the board."

Barb Dorris, outreach director for SNAP, also said the timing of the Clohessy announcement and the lawsuit's filing was "just an unfortunate coincidence."

Clohessy was himself a victim of sexual abuse by a priest when he was a teenager. That fueled his efforts, starting in the 1980s when initial reports of the scope of the abuse began to emerge, to reveal what he and others insisted was a national and global scourge.

SNAP faced years of abuse from Catholics in the pews and denials from the hierarchy until The Boston Globe's landmark 2002 series on clergy abuse finally blew the lid off the scandals and vindicated SNAP's claims and efforts.

Clohessy was even invited to address an emergency June 2002 meeting of the U.S. bishops and delivered a powerful, tearful appeal for them to finally take action against abusive priests.

Shortly afterward, as donations started to come in and lawsuits and settlements began to pile up, Clohessy went from being an overworked volunteer to holding a full-time position as SNAP's executive director.

It was a "cause," Clohessy said, as he and SNAP worked fiercely to push the church to hold bishops accountable.

SNAP never gave ground and became known as a persistent skeptic of assertions that the church, and in particular the Vatican under Pope Francis, was doing anything substantive to tackle the problem.

Clohessy said Tuesday that the years of advocacy had left him exhausted, and he was taking some time off to recharge and look after his health before starting to work again.

"We are eternally grateful for David's dedication to SNAP and its mission over the past almost thirty years," Mary Ellen Kruger, chairwoman of the board of SNAP, said in a statement.

"His passion, his voice, and his kindness have touched us all. We will miss David and we wish him much happiness," she said. "David will always be a friend and an inspiration to SNAP and its many dedicated and hardworking volunteers."