This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On the outskirts of Cedar City, Ally Condie built her own Terabithia.

She and her sister modeled their forest kingdom after the one Jesse and Leslie created in 1977's "Bridge to Terabithia" — though with a dry ravine instead of the creek that figures in the book's tragic climax.

Katherine Paterson's novel is the first of many Newbery award-winning books that grabbed Condie — now a best-selling author — by the heart.

"There are no punches pulled in that book," Condie says. "I'd read a lot of great stuff but usually it had a pretty happy ending. That's a pretty devastating book to read as a kid, but it feels really true."

Condie didn't set out to read all of the Newbery books, but with the local library her main source of reading material — the closest major bookstores were hundreds of miles away in Las Vegas or in Salt Lake City — she ended up reading quite a few from the library's shelf of winners.

"Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry," about a black family enduring violent racism in Mississippi during the Great Depression, was another book that was "so gutting," Condie recalls, "and also very eye-opening. As I kid I was like, 'This doesn't really happen, does it?' "

But there were also "The Westing Game" and "The Witch of Blackbird Pond" — vastly different books that Condie, drawn to mystery and suspense, read over and over.

"You can't really say what a Newbery book is except that it's wonderful," Condie says.

That, in a nutshell, is the main criterion for a book to win the Newbery Medal, awarded each year to the "most distinguished contribution to American literature for children."

—

Publishers Weekly editor Frederick Melcher proposed creating the Newbery in 1921 to encourage authors to write quality books for children, an audience that was an afterthought for most publishers at the time.

Named for an 18th-century peddler of children's books, the Newbery covers books for children ages zero to 14 — which can include picture books, though an award for that format, the Caldecott, was created in 1937. Fiction, nonfiction or poetry is eligible for the Newbery, so long as it's written by a U.S. resident and first published in America.

A 15-member committee — whose members change each year, but are always from the Association for Library Service to Children — consider eligible books on their own merits, not weighing an author's body of work or how a title might fit into the list of Newbery winners.

Some medal-winning books have not stood the test of time or have been surpassed by runner-up Newbery Honor books. Laura Ingalls Wilder won four honors but never the medal for the Little House series; Beverly Cleary won the medal not for any of her beloved Ramona Quimby books but for "Dear Mr. Henshaw."

The most famous snub is probably "Charlotte's Web," passed over in 1953 for "The Secret of the Andes." According to Newbery lore, "Andes" earned at least one committee member's vote not because it was the best children's book, but because it was the first good one about South America.

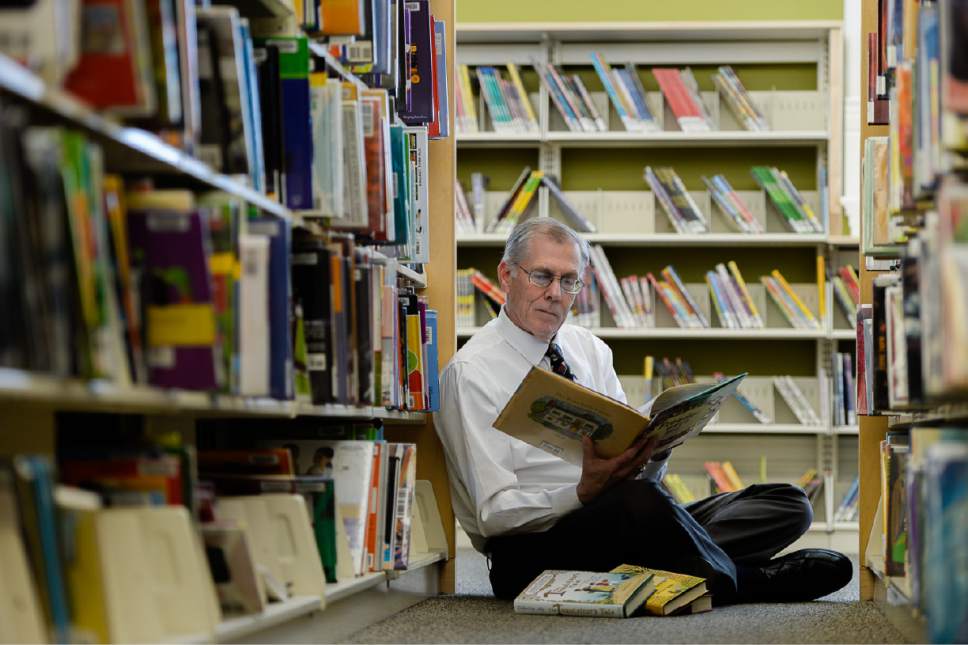

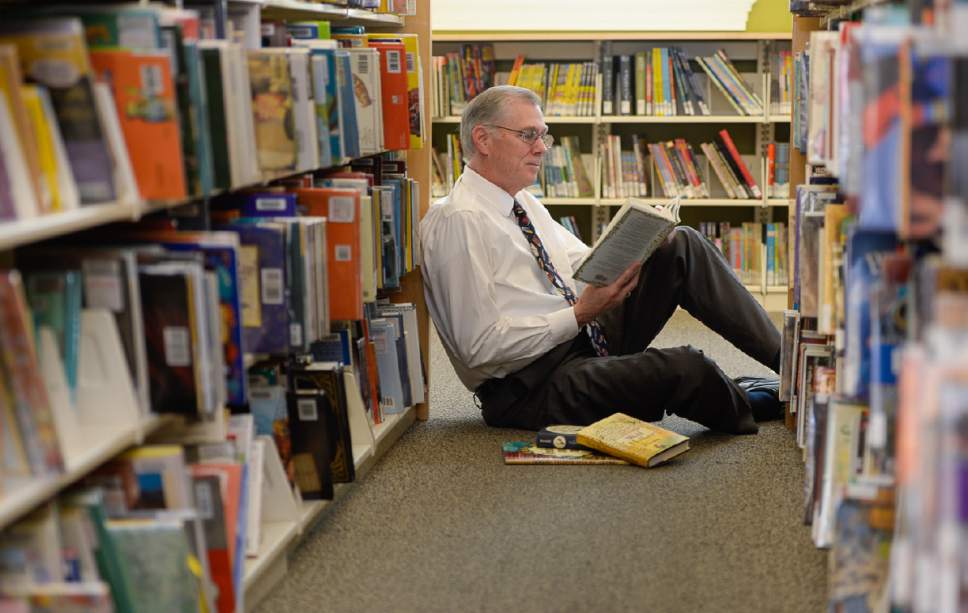

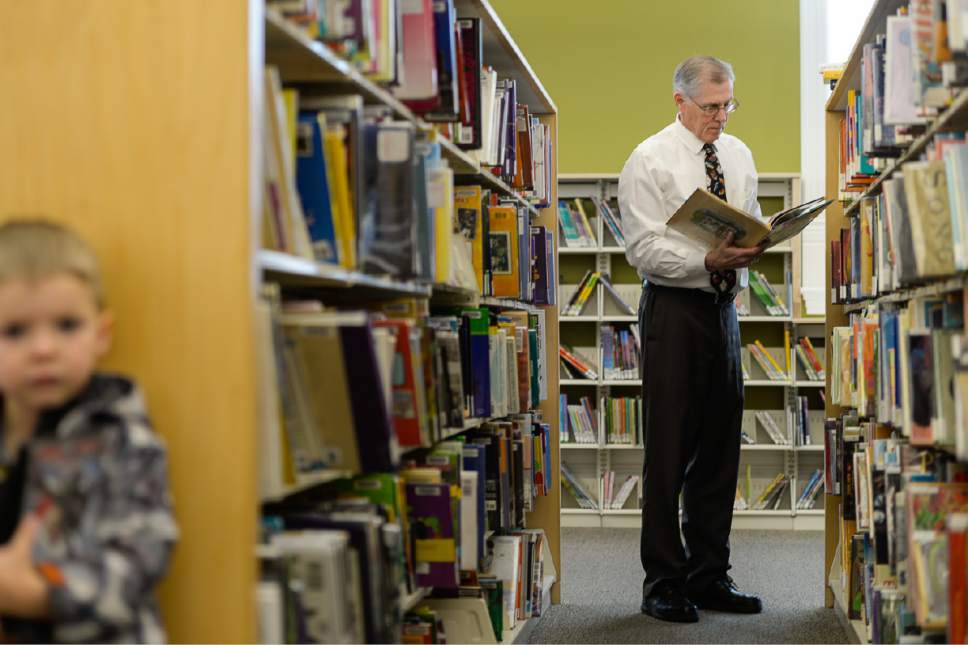

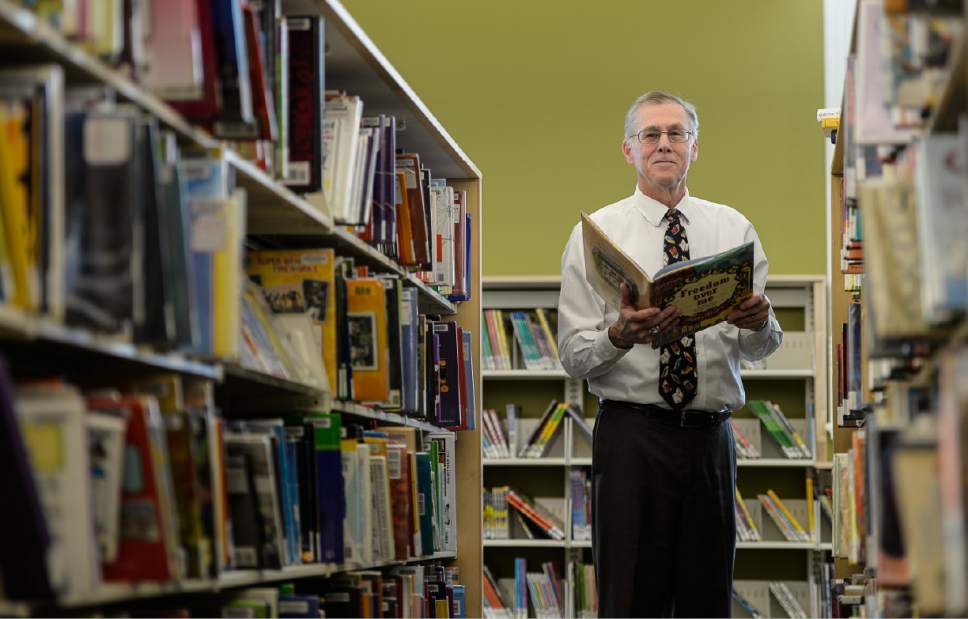

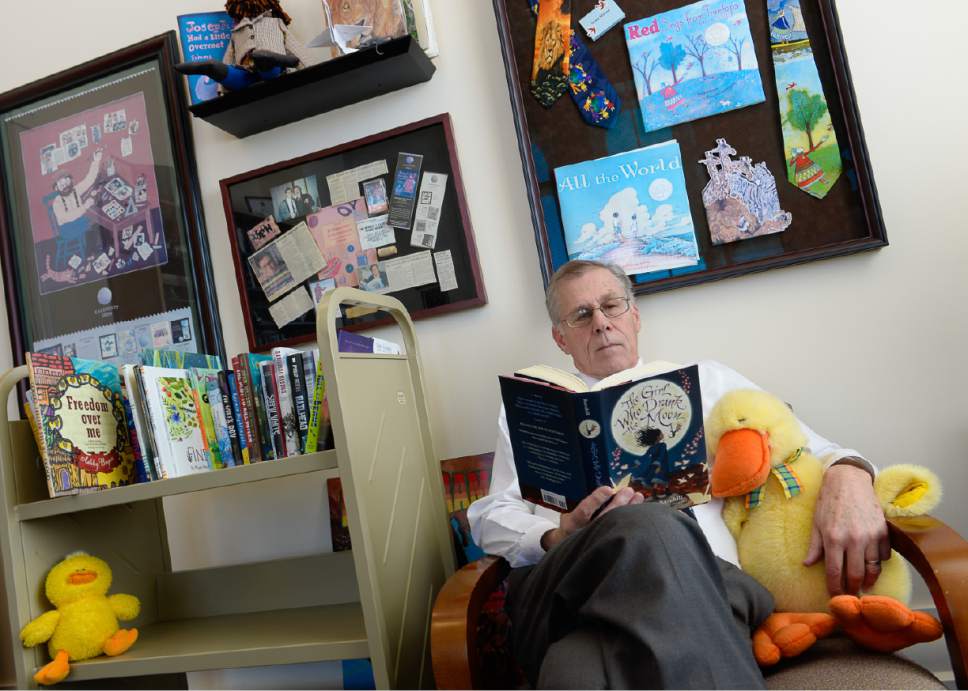

But Provo Library Director Gene Nelson — a member of the 2016 Newbery selection committee — notes that there's never going to be a win that's completely controversy-free; even widely beloved books have vehement detractors.

Nelson should know: As part of the 2016 Newbery committee, he gathered with 14 other librarians last month at the American Library Association's midwinter conference for a top-secret debate over which of the thousands of children's books published in 2016 was the best.

Their choice, Kelly Barnhill's "The Girl Who Drank the Moon," has been well-received so far, he said, but he knows some people will feel frustrated that their favorite didn't win. Others will wonder, "What were they THINKING?"

It's the same thing he's thought many times as winners have been announced.

"I'd like to sit down and say, 'Here are the reasons we didn't select this book,' " Nelson said. "But then I'd have to shoot you once I told you, so that would be the end of that."

Committee members may never reveal which books almost made the cut, or how many rounds of ballots it took to determine the winner, or why a book was an honor instead of a medal.

But Nelson points out that having read probably thousands of books between them, "there won't be anyone who knows this year's books better" than those who made up this year's committee.

—

Nelson estimates he read — and re-read — more than 300 children's books in 2016, devoting about 20 to 30 hours a week to the task.

It wasn't the idyllic life of armchairs and bonbons that book lovers might imagine. He "became a bore" socially — turning down invitations or bringing a book or three to read during meals. He met with fellow librarians and other voracious readers once a month to make sure he wasn't missing worthy titles. He gave books to his grandkids — without telling them why — to ensure the books he liked could really resonate with children and weren't just "adult nostalgia." He took notes and studied the books so that he could recommend — or defend — his choices to the other committee members.

And if he wasn't reading or thinking about what he'd read, he was gripped by guilt or anxiety about all he had to do.

"I wasn't getting a lot of sleep," he says.

Yet it was an experience he wouldn't trade — being on the committee was something he'd dreamed about for decades, since he started his career as a librarian 38 years ago in Las Vegas.

As a kid, he didn't read many Newbery books. He preferred books about sports or boy detectives to historical fiction — which made up most of the Newbery catalog in its first decades.

That changed with "A Wrinkle in Time," which won the Newbery Medal in 1964, when Nelson was 11.

"I was the perfect age for that book," Nelson says. "It talked about time travel, and I thought that was so incredibly cool."

But the next winner, "It's Like This, Cat" — with its contemporary setting, hip lingo and teen protagonist — left him cold.

"I thought it was a stupid book," he says.

He didn't dip back into Newbery books until he was a teenager. He devoured Lloyd Alexander's Chronicles of Prydain (the second and fifth installments of the fantasy series were honor and medal books, respectively) and imaginative titles like "Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH" after falling in love with the fantasy genre and J.R.R. Tolkien.

"He changed my life," Nelson says.

—

It's perhaps no surprise that the medal winner the year Nelson served on the committee was a fantasy — the first high fantasy to take the top award since Robin McKinley's "The Hero and the Crown" more than 30 years ago.

Nelson says he knew "The Girl Who Drank the Moon" was special within "pages."

"It's a totally new take on a fantasy — and I read a lot of fantasy — with multiple layers of reading," he says.

The story centers on a young girl who was selected to be her town's annual baby sacrifice — ripped from her mother's arms to be left in the dangerous forest to appease the witch who lives there.

The witch, for her part, thinks the townspeople are simply abandoning babies. Every year she rescues the infants to find them new homes. But when she accidentally feeds this girl moonlight and imbues her with powerful magic, she decides to raise her — with help from a swamp monster and a tiny dragon who thinks he's a giant dragon.

Younger children could read and enjoy Barnhill's book, Nelson says, but miss some of what's between the lines. When they pick it up to re-read it a few years later — it's that kind of book, he says — they'll find something different.

It went straight into to the pile he'd made of exceptional books. After months of adding and subtracting top titles, he ended up with about two dozen.

But when the committee met in January, he could vote for just three.

The group gathered in a locked room to whittle its choices down, deliberating the merits and shortcomings of titles and casting weighted ballots until a winner emerged.

Though committees have sometimes worked through the night — the titles must be named by 10 a.m. Sunday the weekend of the conference — Nelson said his group came to a consensus sooner rather than later. The process, he said, can be painful.

"Sometimes your personal favorites fall by the wayside," he said. "The first couple times it's pretty hard — it's like somebody shot an arrow through your heart."

Monday morning, the committee gathered at "an ungodly hour" to call the winners on speakerphone. Nelson said he'll never forget the call with Barnhill.

When the committee chairman introduced himself and asked how she was doing, Barnhill answered, "I'm doing pretty good right now because you don't call the losers," Nelson recalls.

"You could almost hear her holding her breath," he says.

Then when the chairman told her she'd been awarded the Newbery Medal, "she just became a wreck … crying and overwhelmed," Nelson says. "The committee is cheering everything she says. It was an incredible moment."

Winning the award often translates into increased sales, but the impact on an author is bigger than that, Nelson says. When someone recognizes you for your writing craft, it gives you a freedom with your publisher to create something new and special — in a way, fulfilling the award's original purpose of motivating authors to write outstanding books for young people.

Twitter: @racheltachel

Join us Feb. 21 for Newbery Night — a party celebrating the award and great children's literature, co-hosted with The King's English Bookshop. Click here for tickets. —

Newbery Night

The Salt Lake Tribune and The King's English Bookshop celebrate great children's literature with panelists including best-selling author Ally Condie and Provo Library Director Gene Nelson, who served on this year's Newbery committee.

When • Tuesday, Feb. 21, 7 p.m.

Where • Panel discussion takes place at the 15th Street Gallery, 1519 S. 1500 East, Salt Lake City. Join us afterward at The King's English Bookshop next door for cake, goodies and prizes.

Tickets • $10, sltrib.com/newberynight Readers' favorite Newbery books

We asked Tribune readers to tell us which Newbery books are their favorites — or which children's books should have won the award but didn't. Tell us your choices at bit.ly/FavoriteNewbery .

Weller Book Works co-owner Catherine Weller, Salt Lake City

1968 • "From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler," by E.L. Konigsburg

Every child spends time feeling unappreciated by their family, and thinking "Oh if I run away they'll appreciate me!" And in the Mixed-Up Files, the girl does run away and she ends up going to the museum and staying there. It's just such a fantastic book of growth — and beauty, and mystery.

Shellie Thornley, Brigham City

2001 • "A Year Down Yonder" by Richard Peck

I love Richard Peck's stories about Grandma Dowdell. She reminds me of my own grandmother. We have listened to this on car trips and the story keeps us laughing but still has its sweet moments.

Krysti Meyer, Clinton — who's read more than 50 Newbery books

1994 • "The Giver" by Lois Lowry

The Giver paved the way for today's dystopian novels. It teaches us to always question our society and its values, and to fight for what we believe is right.

Tribune columnist Ann Cannon, Salt Lake City — who's read more than 50 Newbery books

1963 • "A Wrinkle in Time" by Madeleine L'Engle

I read this book at exactly the right time in my life. The idea that your "weakness" can also be your strength was a novel and important idea for me.

Joseph Peterson, Kaysville

1977 • "Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry" by Mildred D. Taylor

It's one of the few books I've read more than once ... It had a profound effect on me as a person. It shaped a worldview that bends toward social justice, and inspired a dive into other historical fiction and nonfiction learning with regards to our history of slavery, civil rights, and onward. It's also one of the books I remember that really made me a reader, one who loved getting lost in a story, and learning about the world and the way it is through others' eyes.

Pat Ames, Taylorsville

Favorite book snubbed by the Newbery Medal: "Where the Red Fern Grows" by Wilson Rawls (1962)

I remember our teacher reading "Where the Red Fern Grows" to our class over a period of a couple of weeks. When the dogs die, the school bully burst into tears. He was a different kid after that. It was the first time I'd ever seen someone else's life impacted by a book.

Snow Horse Elementary's librariest DaNae Leu, Layton — who's read more than 100 Newbery books

1977 • "Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry" by Mildred D. Taylor

A difficult story told with clarity, humanity, empathy, and even a bit of humor.

Jennifer Palmer, West Valley City

1961 • "Island of the Blue Dolphins" by Scott O'Dell

It's my favorite because of the strength and fortitude the main character showed in the face of her isolation and hardships. I re-read it constantly as an elementary student. I had a friend who asked me why I didn't read something new, and I told her I hadn't found anything better yet.

Christy Rasmussen, Orem

1963 • "A Wrinkle in Time" by Madeleine L'Engle

I really bonded with Meg. She was smart, and bookish, and loved her little brother more than anything. She was brave and determined to do whatever she had to in order to get her father back.

Karla Burkhart, Sandy — who's read more than 100 Newbery books

1950 • "The Door in the Wall" by Marguerite de Angeli

I read it when I was quite young — I was 6 when it was awarded. I think it had a big influence on the books I picked thereafter. I still re-read it often.

Steven Nordstrom, Provo

1963 • "A Wrinkle in Time," by Madeleine L'Engle

Of all the Newbery winners, this book had the biggest impact on me as a child. I read many of the winners as a kid, and there was a golden era of winners in the 1960s and '70s of classics still recommended by parents and librarians, and read and enjoyed by children.

My runner-up favorite is "The Bronze Bow" (1962, by Elizabeth George Speare). This was my favorite read of 2016. Seriously. —

This year's Newbery winners, chosen by a 15-member committee that included Gene Nelson, director of the Provo Library:

Medal: "The Girl Who Drank the Moon," by Kelly Barnhill

Honors:

• "Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life," by Ashley Bryan, a collection of poetry and collages.

• "The Inquisitor's Tale: Or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog," by Adam Gidwitz, a humorous epic inspired by "The Canterbury Tales."

• "Wolf Hollow," by Lauren Wolk, a story about a young girl in rural Pennsylvania dealing with an especially cruel bully during World War II.