This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

New research from Brigham Young University shows police departments are changing the way they handle the submission of forensic evidence collected in sexual assault kits.

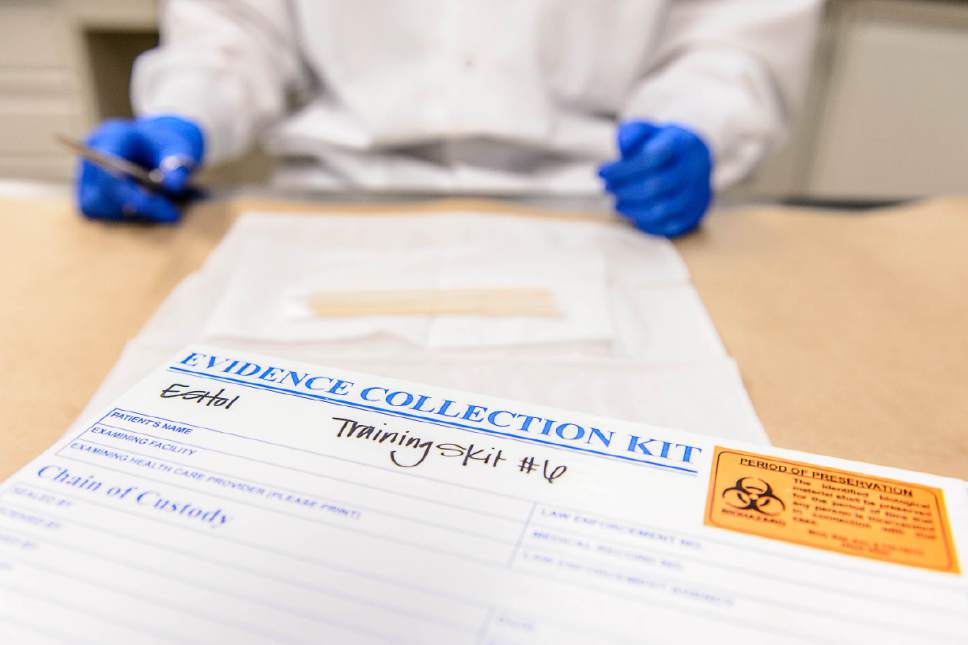

A study released last year showed that most evidence gathered in rape kits was never submitted by law enforcement to the state crime lab for DNA analysis.

It was "justice denied," BYU nursing professor Julie Valentine said last April, after releasing her initial findings.

But Valentine released a new set of findings this week with "encouraging" results: In 2014, 75 percent of sexual assault kits in Utah were submitted by law enforcement to the crime lab.

Her previous research, which examined submission rates from 2010 to 2013, found that 38 percent of rape kits were submitted.

"I was thrilled," Valentine said Thursday of the results. "And I also was so proud of law enforcement. It really shows, across the state, that law enforcement have listened to the community and the crime lab saying, 'Yes we want these kits.' "

The study found that Washington County showed the most significant improvement in submitting rape kits to the crime lab. From 2010 to 2013, 18 percent of kits were submitted — but in 2014, the submission rate jumped to 93 percent.

Washington County Attorney Brock Belnap said last year that all police agencies in his county are now submitting every kit for testing. Previously, police would send cases for DNA analysis only if the assailant was unknown or had denied sexual activity took place.

This shift to sending all sexual assault kits to the crime lab is happening in police agencies across Utah. West Valley City police, for example, also have implemented a policy in which they submit all kits to the crime lab.

West Valley City police Sgt. Steve Katz said in a recent interview that the department changed its policy after Utah officials in 2014 discovered an estimated 2,700 rape kits across Utah sitting on police departments shelves, untested.

This was a "problem," Katz said.

"[With] the sensitive nature of the case and the complexities of the case, at the end of the day, they can be very difficult cases," Katz said. "Anything that can assist us in getting evidence to further that investigation, we're excited about."

Valentine said she has seen a nationwide change in how sex assault cases are investigated and prosecuted, including that law enforcement has started believing victims more often.

The researcher said that while it is important for the kits to be tested for victims to have justice, it is also critical for the truth. In her study, Valentine said, she has found nine cases in which the kits were submitted and the DNA showed the initial suspect wasn't the perpetrator.

"We could have had nine individuals charged with crimes and incarcerated that didn't commit [those crimes]," she said. "DNA is DNA. It's science. It's a tool to help establish justice, and a tool to make our state safer by identifying serial perpetrators."

That is why, Valentine said, it is important for Utah lawmakers to pass a bill now before them that would mandate all rape kits be submitted to the crime lab within 30 days, with testing required by a to-be-determined deadline.

HB200, sponsored by Rep. Angela Romero, D-Salt Lake City, also would create a tracking system for rape kits and trauma-sensitivity training.

It also is critical, Valentine said, that lawmakers provide an estimated $2.4 million to fully fund the bill, so the crime lab has the financial support it needs to handle the expanding workload.

If it is not funded, Valentine said, the backlog problem will simply be shifted: Rape kits will go from sitting untested on police department shelves to sitting on crime lab shelves.

Crime lab Director Jay Henry said at a recent legislative committee hearing that the $2.4 million would pay to hire extra lab technicians to handle the extra work, along with chemicals and other supplies needed to perform more than 900 tests per year.

Henry told The Salt Lake Tribune recently that while the crime lab has received financial support from the Legislature in the past — including funding for a new crime lab and updated mechanics — more money is needed to hire staff.

"We have the facility," he said. "We have the equipment. Eventually, you get to the point where you really need more bodies to test the evidence. What we're seeing is a sexual assault kit test increase. … A lot of the agencies have said, 'We're just going to turn them all in now.' "