This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Maybe it's part of the work of a writer to dance with those who have passed on.

If you turn over the dirt at a place where something has happened, you're stirring up history, as the poet Joy Harjo wrote.

Or maybe literary inspiration can be captured by that famously quoted idea of writer William Faulkner, about how history isn't really dead, or even really past.

That's the metaphorical link between two recent memoirs by Utah writers Brooke Williams and Scott Abbott, whose lives are shadowed by dead relatives.

Williams' ghost is his great-great-grandfather William Williams, who died in Wyoming along the Mormon Trail. In contrast, Abbott is haunted by someone he once knew well, his younger brother, John, who died at 40 in 1991 of complications from AIDS.

Williams, in his new memoir, "Open Midnight: Where Ancestors and Wilderness Meet," imagines a story from the barest outlines of his great-great-grandfather's life. In the decade or so since Williams "met" his ancestor, the writer came to believe he has been guided to discover what might be called an inner wilderness.

His editor, Barbara Ras, calls the book "completely original," praising the writer's voice as "completely evolved." "In a totally sophisticated and personal voice, he speaks so directly to the reader without any hesitation," says Ras, a poet who recently retired from the environmentally focused Trinity University Press, which she founded. "He found the courage to bring together unlikely combinations."

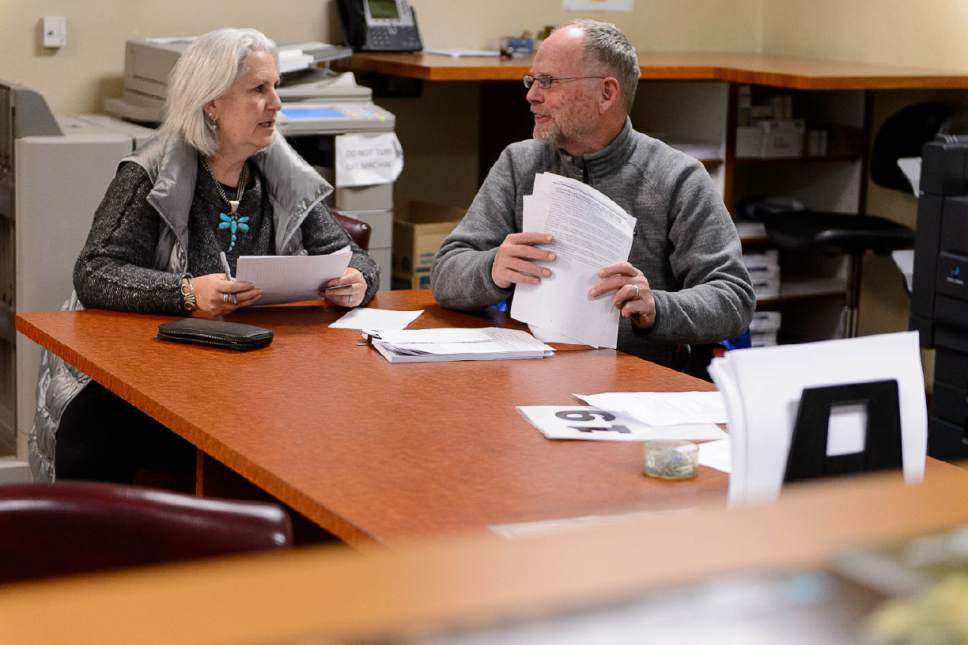

In Abbott's book, "Immortal for Quite Some Time," the Utah Valley University philosophy professor crafts what he calls "a fraternal meditation." In a fragmented, intellectual style, he includes challenges from an unnamed female voice and questions from his dead brother.

Abbott's editor, John Alley, at the University of Utah Press, calls the book "an exciting, entertaining read" because of its fragmentary style, praising the writer's bravery as he left his job at Brigham Young University and membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Considered together, these two books offer fascinating cultural reconsiderations of Mormon beliefs about communication between the living and the dead.

For Williams, the dead are all around us, serving as something like spiritual guides, or reminders of what Carl Jung termed the "collective unconscious."

Abbott says he thinks the dead are dead. And yet: He wrote a book to hold onto his brother's memory, even inventing fragments of conversations he wished he could have with him. "Keeping it in fragments at least keeps the sense that this story is not finished," he says.

—

Uprooted • When Williams moved with his wife, writer Terry Tempest Williams, to Castle Valley in 1999, he was the first member of his immediate family to choose to settle more than 50 miles away from Salt Lake City. "But then I'd always been the difficult one," he writes.

The Williamses' environmental activism earned national headlines last February after they bid on Bureau of Land Management oil and gas leases north of Arches National Park, as part of a climate change protest. Their winning bids on 1,120 acres prompted them to incorporate an energy company, Tempest Explorations LLC. "You cannot define our definition of energy," Tempest Williams said at the time.

In October, the Interior Department refunded their money and withdrew the leases because they weren't planning to develop the land. Williams says they have filed an appeal for what they argue is "special treatment."

That's one of the untold backstories that anchor his book. During the time he was writing "Open Midnight," Williams was employed by the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance to "ground-truth" — that is, to make sense of maps created by aerial photographs. He spent long days alone in remote places, accompanied by his dog, Rio, and his truck, which he refers to as Ford.

After moving to southern Utah, Williams says he felt like a newcomer — nonnative, that is — as he was falling in love with the landscape. He began to consider what it means to be native, and then he began to wonder about his ancestral roots in England.

From a pedigree chart, the name of William Williams seemed to jump out at him, as if it were written in neon ink. Williams' life is recorded in an outline of dates: He was born in 1808 in Shrewsbury, England, near where Charles Darwin was raised. He died in 1863 somewhere in Wyoming along the Sweetwater River.

What history books don't record about his ancestor, Brooke Williams beautifully and thoughtfully invents. In the decade or so that he wrote the book, the writer came to believe William Williams was guiding him to new ideas. "I basically used my imagination to fill in the blanks of the story, which may or not be true."

In an interview, he explains it this way: He attributes moments where his attention is alerted to something out of his focus to the influence of his ancestor. "My life is infinitely more interesting now that William Williams is a part of it," he says.

After years of searching outdoor adventures or bagging mountaintop views, Williams instead found a new peace with solitude. In lovely, economical pages of close observation, most of what happens in the book is the result of a quizzical narrator's introspection. He began to feel truth coming up from the ground.

As a longtime activist, Williams began to realize that his focus on the strategy of saving wildnerness wasn't as relevant as another question: How does wilderness, instead, change us?

It's biological, he asserts. "The thing that I believe is that when we access this inner world, this biological place inside of us, there's an organism that teaches us how to pass life along to the future," Williams says. "There's a place inside of us, if we can access it, that lets us know what the universe wants."

—

Postmortem • Abbott's book begins in 1991 with the description of his brother's body in the mortuary after an autopsy. He observes his younger brother's uneven teeth and feet, both features resembling his own.

In "Immortal," he traces their shared Mormon boyhoods in Farmington, N.M., and their LDS Church missions, and then takes trips to places his brother lived and worked in Boise, Idaho, and San Diego.

He reads his brother's notebooks and carefully considers his possessions, looking for clues about who his brother was. As he regularly changes the batteries in his brother's Miller beer clock, the ticking becomes a presence in the narrative and provides a metaphor for the book's cover design.

As the writer considers the brother he hardly knew as an adult, Abbott also interrogates the way his religion treats gay people. His public challenges about campus intellectual freedom threaten his faculty position at BYU and eventually splinter his marriage to his wife, the mother of his seven children.

"I set out to write a book about my brother, and it became a book about myself as well as my brother," he says, explaining why he's uncomfortable with the label of "memoir." "My book is fragmentary. It requires that a reader put it together in ways that a normal story doesn't."

Perhaps the book's most interesting revelation to the Mormon intellectual community is that Abbott outs himself as the author of an anonymous 1995 Sunstone magazine essay that revealed plagiarism in an address by then-BYU president Merrill Bateman about moral relativism.

The essay prompted national news stories, and according to Abbott's account in the book, Bateman apologized for careless attribution. Just weeks after its publication, the anonymous Sunstone writer was threatened with the curses of Isaiah quoted by LDS Elder Boyd K. Packer during the church's general conference session.

In "Immortal," the dual story of the writer and his brother, like most memoirs, becomes a meditation of memory, which, as Abbott writes, "is a slippery medium. Slippery and malleable."

The years he lived through in writing the book dramatically changed his life and changed his memories of his brother. (An earlier version of the book won the Utah Arts Council's writing competition for creative nonfiction.)

Even as he left behind his BYU job and membership in the LDS Church, he aimed in the writing be fair to the rich culture and belief system that shaped him and his family. (Abbott now is a professor of humanities and philosophy at Utah Valley University.)

In the book, he records a family note from his brother that urged him to accept their mother's faith. "Mom's a person herself. Share her right to believe!" After that, his brother wrote the question that inspired the entire book: "Are we friends, my brother?" "That question undoes me every time I read it," Abbott writes in "Immortal."

"I guess the shock of his death made me want to do some of the work that a relationship requires," Abbott says. "Which is ironic, because it was in that moment when there couldn't be a relationship."

facebook.com/ellen.weist —

Brooke Williams reads from 'Open Midnight'

When • Thursday, March 2, 7 p.m.

Where • The King's English Bookshop, 1511 S. 1500 East, Salt Lake City

Tickets • Free

—

'Open Midnight: Where Ancestors & Wilderness Meet'

By • Brooke Williams

Publisher • Trinity University Press

Pages • 214

Price • $16.95

More • Williams' most recent book, edited with his wife, writer Terry Tempest Williams, was a Torrey House press reissue and response to British writer Richard Jeffries' 1883 autobiography, "The Story of My Heart."

'Immortal for Quite Some Time'

By • Scott Abbott

Publisher • University of Utah Press

Pages • 256

Price • $24.95

More • Abbotts' most recent book, written with UVU colleague Sam Rushforth, is "Wild Rides & Wildflowers: Philosophy and Botany with Bikes," based on their mountain-bike adventures on Utah County's Great Western Trail. The book grew out of the pair's columns originally published in Catalyst magazine.

Also • His next book, "Intimate Fences: Constructing the Meaning of Barbed Wire," written with Lyn Ellen Bennett, will be published in October by Texas A&M University Press.