This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Draper • They escape from the Utah State Prison using their pencils and pens.

For inmates, working on their art is a way to forget about being locked up for their crimes. It's a way they see the places and people they long for. It's a way to validate the changes they're trying to make, hoping that if they get to the outside they will never come back.

"It's black and white in here and color out there, " says Roy Gallegos, 47 who has been incarcerated 26 years for rape of a child and aggravated murder. "[Color] gives me a sense of belonging to society."

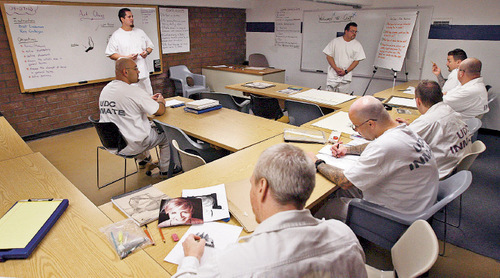

Once a week at the Utah State Prison in Draper, inmates volunteer to teach their peers how to develop their art skills. Not a penny of taxpayer money is spent on the inmate art classes, which have been offered for two years in the "C" block — better known as "Charlie Block" — at the Wasatch building.

In the two classes of about 10 students, there have been no fights between the various types of inmates, from sex offenders to murderers, which is rare, prison officials say.

"[Art] breaks those barriers," says Lt. Kent DeMill, who oversees the Charlie Block and gave the approval for the art classes. "We've had no problems at all."

—

'Do something good.' When Gallegos entered the prison in 1984, he sold about eight drawings a month to inmate gang members, who used them to create tattoos or give as gifts.

"It was survival," he says. "You have to have skills, hustles in order to get by."

But in the early 1990s, Gallegos said, he stopped drawing gang art — Aztec Indian images, prison scenes or sketches of women. He instead began to draw landscapes, using National Geographic magazine to envision an African safari; his art became a "gateway" for him.

"It would create the illusion that I was there" in whatever I was drawing, he says.

In summer 2008, Gallegos and fellow inmates Bret Lindeman and Jason Biggs sent DeMill their proposal to teach an art class and offer it to the other 65 inmates in Charlie Block — considered the "honors block" with the most privileges in the prison.

DeMill says prison officials' concerns included safety issues raised by the extra art supplies they would be allowed to use and keep in their cells. Still, DeMill says, it was obvious the inmates were "knowledgeable," were working together and knew what they wanted to do.

"When you get something like that in prison, you run with it," he says.

Gallegos and Lindeman teach two classes on Sundays, each with about eight inmates who must buy their own supplies. Inmates make 40 cents to $1 an hour. The two teach the men various drawing techniques and elements of design, using more colors and professional art supplies than the dozen or so arts and crafts items available in the commissary.

The success of the art classes stems from Gallegos' and Lindeman's dedication, the cooperation of the inmates and the limited number of inmates on the block, officials say. The art class is a way for them to work on a skill, gain self-worth, help their peers, and, most importantly, express themselves, prison officials say.

"They start seeing they can do something good," says Michael Ryan, an 11-year officer who oversees the programming in Wasatch. "It gives them something to be proud of."

Lindeman, 35, convicted of first-degree murder for the stabbing death of his ex-wife and scheduled for a parole hearing in 2024, says focusing on art since he entered prison almost 10 years ago has kept him out of trouble.

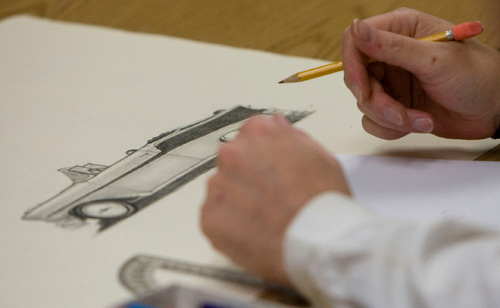

Drawing for sometimes up to five hours a day helps him "zone out from the rest of the world." He's also grateful he has the opportunity to teach other inmates about his passion.

"There's no excuse for what I did," Lindeman says. "I'm trying to do something positive out of something negative."

—

The power of art. William "Buzz" Alexander is a University of Michigan professor nationally recognized for the Prison Creative Arts Project he launched in his state's 40-some prisons 20 years ago. He contends art can change inmates' lives — and the lives of the next generation.

The empowerment inmates gain from developing their self-esteem and education through art projects can make them better parents, he says. In his new book, "Is William Martinez not our brother?" slated for publication this month, Alexander argues art programs are necessary in prisons.

"Their situation improves because of what they're doing," he says.

It's hard to track the impact of the art project on the inmate recidivism rate in Michigan, he says, but it has clearly helped with disciplinary problems. The average number of disciplinary tickets in inmate files is about 17; it's just one if the inmate is participating in the project.

Utah inmate Carole Alden, who recently volunteered to teach an art class to other women in the Draper prison, agrees art is transformative.

"[Art] turns into a covenant of hope," she says. "It helps people crawl out of their hole."

As a kid, Alden used to get in trouble for drawing on walls and sneaking water into the sand box to build caves for toy dinosaurs. She eventually studied sculpting in Denver. Years later she participated in the annual Utah Arts Festival, where one year she built a floating dragon 18 feet tall and 90 feet long.

But when Alden entered prison in 2007, convicted of manslaughter in the death of her husband, she was depressed and suicidal.

"When people are in places like this, they forget, lose hope and confidence in themselves," she says. "People look at you like you're something they scraped off their shoe."

Even though Alden, now 50, had not drawn since high school, she found refuge in the limited art supplies she had access to in prison. She felt the skills she was sharing were a form of therapy for women. "It helps them get in touch with their emotions they cover up with drugs."

But the class she was teaching was recently axed due to staff changes.

At federal and state prisons nationwide, funding for art programs is rare. Programs typically are initiated and funded by community volunteers from nonprofit groups to colleges, experts say.

In Draper, some prison officials and inmates remember an informal art class briefly offered in the early 1990s; other workshops have been held on rare occasions when volunteers initiated them.

The Draper prison's budget is $69.7 million; $12.1 million of it is used on programming for inmates. No money is used on arts programs or supplies, according to department spokesman Stephen Gehrke.

In Utah, 66 percent of paroles will return to prison within three years. Prison officials say they don't track inmates in art classes, but Ryan says from his experience, those involved in art and education programs "normally don't come back."

—

Inmates 'want art.' Gallegos, who doesn't have a scheduled parole hearing, says his vivid art is what keeps him going. "Color is a signifier of freedom," he said.

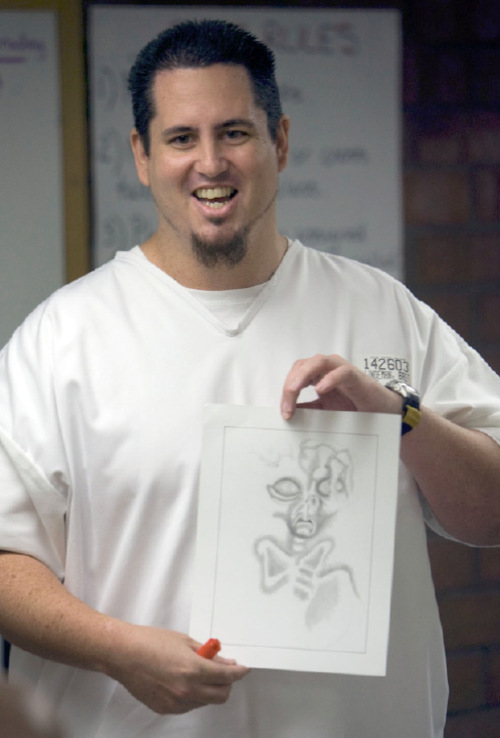

He is now drawing iconic images, from cartoon characters to skeletons with flags, and mailing them to his wife of four years, Claudia, in West Jordan. She's putting them on T-shirts, among other items, to sell. He's taking distance learning art classes, at $800 a semester.

Word of the art classes in Charlie Block has spread throughout the prison.

Rudy Perez has served 12 years for three counts of second-degree felony sexual abuse of a child, and is slated for a parole hearing in 2011. He immediately signed up when he recently moved into Charlie Block. He wants to learn how to draw eyes, which he calls the windows to the soul.

Perez, 54, says it's great to be around other positive and encouraging inmates. He hopes the prison considers starting the classes in other blocks and facilities.

"[Inmates] want art," he says. "Once they open the doors, they'll come like cattle."

Robert Millar, convicted of first-degree felony of aggravated sexual abuse of a child, started serving time in 2005 and is scheduled for a parole hearing in 2011. He's been taking the art class since it started.

Millar, 43, says the class helps him stay calm in a "chaotic world."

"When I'm drawing a landscape, I'm on that river for an hour or as long as it takes me [to draw it]," he says. "I'm relaxed. I'm peaceful."

Arts and crafts in the commissary

Materials are available to inmates who have earned certain privilege levels. Pens, pencils, envelopes, note pads and other writing materials are also available.

Crochet hook • $1.29

Plastic crochet needle • $0.60

Drawing pad 11X14 • $12.18

Drawing pad 9X12 • $8.79

Yarn (various colors) • $2.30 - $3.98

Paint (various colors) • $6.44

Brush (various sizes) • $3.79 - $5.95

Charcoal pencil • $1.16

Colored pencils • $1.95

Gel pens (various colors) • $1.45 - $2.49

Water color pencils • $4.34

Glue • $0.79

Glue stick • $0.30 —

Utah recidivism

Of the 2,573 released parolees, 1,708 — 66 percent — returned to prison by the 36th month.

Of those who returned, 399 — 23 percent — returned to prison for a new sentence and 1,309 — 77 percent — returned to prison for a parole violation.

Based on 2006 parole releases in Utah —

Utah Department of Corrections inmates

By location

Draper prison • 3,802 or 57%

Gunnison prison • 1,505 or 23%

County jails or on out-of-state compact • 1,306 or 20%

Total • 6,613

By gender

Females • 536 or 8%

Males • 6,077 or 92%

By race

White • 4,350 or 66%

Minority • 34%

Including:

Asian/Pacific Islander • 193 or 3%

Black • 463 or 7%

Latino • 1,269 or 19%

American Indian • 285 or 4%

Unknown • 41 or 1%