This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For months, Jimmy Lucero worked with a group of teenage girls to help them complete a series of tile images that sparkle like ornaments on a 600 W. 200 North roundabout in Salt Lake City.

First came lessons in drawing. Then came lessons in painting. Finally, the girls learned to translate their images into detailed tile shapes.

Near the final stage, Lucero pushed his charges as far as they would go, forming and creating their own images: cherries, an embryo and skeleton, a naval officer and a beehive, plus other subjects unique to their neighborhoods.

If someone needed help, Lucero was there. "Remember how hard we tried to make this an image we could understand?" he asked the girls. "When you're older and I'm dead and gone, you all can drive by this and say to your families, 'See what I did when I was a kid?' "

Amanda Torrez, 14, Valentina Alcantar, 15, Alayna Dardon, 16, and Gabby Lucero, 17, surveyed their work with pride. "As time went on, we needed him less and less," Alayna said.

Cultivating independence is one of Lucero's core ethics as an artist. So is advocating the importance of tireless work, battling fear and painting the best, most provocative paintings possible using semi-gloss house paint. In quarts, preferably.

Art, with political context

Lucero turns out his own paintings forged, sometimes even chilled, in a silent language of political context only an extended gaze can unlock. He draws upon the Latino tradition of art as mural and message as backdrop, as well as his training while earning a 2003 MFA in painting from the University of Utah.

Some of his paintings are warmer than others. "Chavez Crossing the Rio" appropriates the famous imagery of "Washington Crossing the Delaware" to generate resonance between the nation's founding and immigrants' struggles for dignity.

Others, such as "El Amigo," invite a dizzying game of role playing between traditional Mexican heroes Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata and the caricature of a U.S. businessman. Most of what Lucero calls his "border paintings" seethe with a saturated hue of light green, symbol of the greed pervading both sides of the United States-Mexico border.

Winning the game of the American dream

One of Lucero's most striking works of late isn't a painting at all, but a hole of miniature golf, now on view at the Salt Lake Art Center. For the center's "Contemporary Masters" exhibition, Lucero's contribution places the golfer in immigrant shoes.

To win the game of the American dream, hit your ball across the border, past Arizona's sand trap of immigration law and into the hole of Washington, D.C.

"It's a good-natured piece, even as it raises questions worthy of more dialogue," said Adam Price, the center's executive director. "It's quite popular."

The more dialogue his work sparks, the better, Lucero said. When the full-dress exhibit of his border paintings hit Art Access Gallery two years ago, director Ruth Lubbers said one woman phoned the gallery promising to picket Lucero's works in protest.

"There was a lot that was said in those paintings," Lubbers said. "A lot of so-called social justice artwork doesn't sell well, but Lucero has a real gift."

The arc of time

The protest never materialized, much to Lucero's chagrin. Immigration is an issue as close to his heart as human dignity and the American dream. Who's afraid to talk about that?

He was intrigued by the idea of someone protesting an art exhibition. He thought maybe he could talk to the woman. "Too bad she never showed," he said.

The arc of time Lucero invoked for the girls at the roundabout mirrors his own. A third-generation Mexican-American raised in Santa Barbara, Calif., Lucero, 53, said he counts himself fortunate to have grown up in a time and place where animosity toward anyone was a rare commodity.

The adults and kids he grew up with socialized across racial and socio-economic lines. Lucero fears that neither he, nor his wife and two children, will see that environment again.

"I was very fortunate," he said. "Now, with all the heated words about immigration and even religion, I don't think I've ever seen so much hatred in this country in my life."

Blue-collar roots, and art on the side

A janitor's son who never saw an empty table thanks to his mother's cooking, Lucero also rarely saw a spare hour. That was thanks to a family schedule that kept him either in school, at the neighborhood Catholic church or at work in his uncle's blacksmith shop.

He got the art bug thanks to free classes by painter Ivan Webster at Santa Barbara's Palm Park. When he became skilled enough to paint his first portrait and sold it for $50, Lucero knew art would, at minimum, serve as a hobby throughout life. He started waking up at 5 a.m. to paint before school.

"I always felt very fortunate to have those free art classes as a kid. Now I want to give back wherever I can," he said.

Lucero fell under the spell of artist Manuel Unzueta at the Santa Barbara City College, and his studies in figurative drawing and painting also led him to study the science of the human body. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, then worked in science labs at the University of California Davis, and Stanford University.

Returning to art — with house paint

Lucero and his family moved to Salt Lake City in 1992, and he and his wife worked at science labs at the University of Utah's school of medicine. When working together proved too cramped for the couple, Lucero's wife encouraged him to turn his love for art into full-time study.

Lucero forged his own style of painting, using only five hues of hardware-store house paint: red, yellow, blue, black and opaque white. Such paint was not only inexpensive — and more affordable for art students Lucero teaches at the University of Utah and Westminster College — but less toxic than traditional oils. For a paintbrush, Lucero chose boar's hair. Its distinctive stroke left evidence of the artist's labor.

Inspired at first by the naiveté and narrative potential of children's toys, Lucero crafted a series of paintings rendering puppets, robots and other figurines in boat scenes near lakes and oceans. While a graduate student at the U., he was awarded the Howard Clark Art Scholarship for most outstanding graduate work.

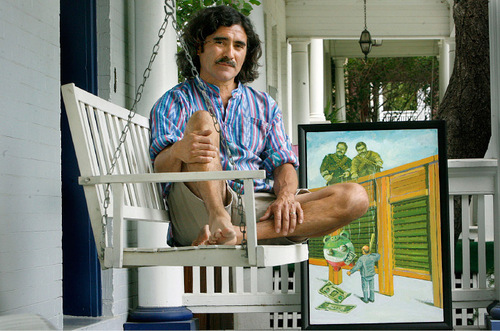

Painter in a Hawaiian shirt

"He definitely didn't fit the stereotype of an angst-filled artist," said Kim Martinez, associate professor of painting and drawing who worked with Lucero when he was a graduate student. "I don't think I've ever seen him in anything but a Hawaiian shirt."

Whether lunching at Red Iguana, or deep in the center of his basement studio at home, Lucero punctuates almost every sentence with a laugh or smile. Even as he has turned his attention from children's toys to more political themes surrounding immigration, his voice hasn't lost its trademark cheer.

Lost in the endless immigration debate, Lucero said, is the strength of the human spirit to never cease striving in the face of staggering costs. A supporter of work-furlough programs for immigrants, he's bothered when politicians play up drug trafficking along the border instead of the hundreds who die trying to cross the border, or women murdered by the score in Ciudad Juárez.

What happened to a better life?

"What person doesn't want a better life for their children?" Lucero asked. "What would people's opinion be if the laws were just as strict back then, when their families wanted to come to this country? This is the land of opportunity. What happened to that?"

The calavera, or Spanish "skull," has become a recurring motif in Lucero's recent paintings. Rather than toy with their macabre connotations, he points them in reverse, toward the impulse of life, hope and regeneration.

In "Night Crossing," a painting in process, Lucero lines calaveras up in marching order toward the border wall, crossing from Mexico in the United States. The moment they cross that partition, they come alive as working, purposeful and living people.

"It's an American story, of course," Lucero said, smiling. —

Art's hole in one

P Artist Jimmy Lucero's work is included in Contemporary Masters, a fully playable artist-designed exhibit of miniature golf.

When • Open for playing Tuesday, Sept. 14, to Thursday, Sept. 16, 11 a.m.-6 p.m.

Where • Salt Lake Art Center, 20 S. West Temple.

Admission • Free.