This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

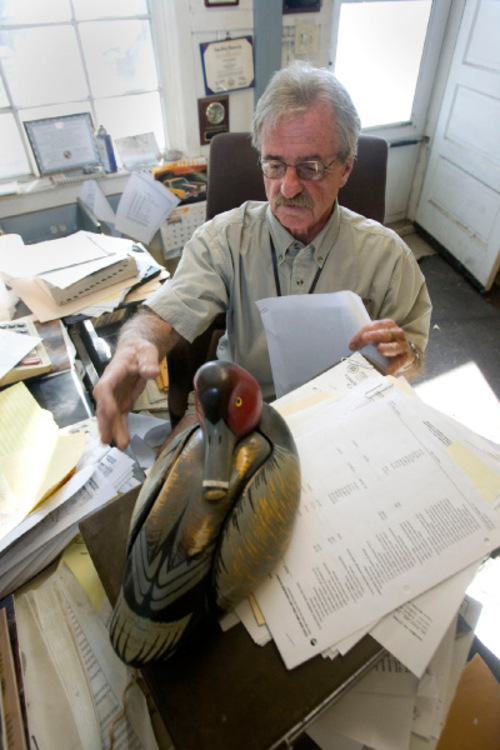

Hooper • Papers, some dating back to the 1930s, clutter the floor of Ogden Bay manager Val Bachman's Civilian Conservation Corps-era office.

Bachman is a friendly man with a cell phone hanging from his neck on a magnetic attachment. He invented the device made from a fishing net because he kept drowning phones in the water he so carefully manages on the 34,000 acres that include Ogden Bay.

There is much to be done before he retires from a job he clearly loves, despite its ridiculously long hours. He lives in a house next to the office, often working seven days a week to help create habitat for the 250 species of birds that use the state refuge and helping thousands of visitors.

"It is definitely a full-time job," he said. "You have no personal life. You live here. This is the last area in Utah that has a live-in manager. It's seven days a week, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. You have to love the job."

There is much work to be done, both in the field and in the tiny, cluttered office.

He is trying to electronically catalog past habitat plans, some dating back to the 1930s when the refuge began.

Bachman, who has worked at Ogden Bay since 1978, might be the only person on Earth who knows where all the refuge's 280 head gates are. The gates control where the water to create wildlife habitat goes, and Bachman just built 12 new ones on the area's newest impoundments.

"I need to map all of that before I retire," he says with a grin.

Ogden Bay was conceived in 1937 as a joint venture among the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (then the Department of Fish and Game), the Weber County Wildlife Federation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps, the latter of which built the dikes, Bachman's office and the ancient garage still on the property.

In 1938, shortly after Congress passed the Pittman Robertson Act (Federal Aid to Wildlife), which took excise taxes on hunting equipment and dedicated them to wildlife habitat, Ogden Bay became the first area in the nation to use the funding.

Marcus Nelson became the first superintendent of Ogden Bay, which started as a federal refuge before the state took over. J.B. Lowe, who would become nationally famous as a teacher and author about waterfowl management, became the second. Then Noland "Dooley" Nelson took over, working on and off for 43 years.

Bachman was Nelson's assistant after spending two summers on lonely Gunnison Island in the middle of the Great Salt Lake doing research and a short stint surveying Great Basin wetlands for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

These days, he creates habitat.

"What people have to realize is that not one acre here is natural," he explained. "Thousands of acres are man created. They were gone when we started."

That gives Bachman the ability to exert amazing influence over the environment and the ability to help just about any of species of bird that needs it. Instead of just documenting losses as many biologists do, he can actually manipulate water and habitat to make major changes. He proudly stated that he might have either rebuilt, restored or created more wetlands than anybody else in the United States.

"How could that not be rewarding?" he asked.

For example, when peregrine falcons were endangered, he helped build hack towers as nests. When there was a need to increase bald eagle populations, he figured out a way to keep water flowing in some parts of the refuge to provide plenty of carp for winter feed. Now, 150 eagles winter at Ogden Bay and the big birds have established their first nests.

Glossy white-faced ibis were considered threatened at one point. Bachman figured out their habitat needs and now thousands of them nest. The same thing happened with snowy plovers and pheasants.

"There are very few species that, if I felt the need to increase, you couldn't do it on Ogden Bay," he said.

These are both good times and bad as Bachman winds down his long career. He could retire now, but gives the impression that he will stay a few more years to finish some pet projects.

On the good side, water — the lifeblood of these marshes — is more plentiful and its quality is surprisingly good, though that could change with the needs of a growing population. Bachman said last year's duck hunt was the best in years and a new generation of hunters who spend more time and money in the field is developing.

The downside is that many hunters are dying off and fewer are replacing them.

"Our big threat is funding," he said. "We are doing some huge projects, but none of it with DWR money. It's all outside money. We've had a loss of young hunters. Money for basic operations and maintenance, license sales and Pittman Robertson money is decreasing."

There is also the problem of phragmites, an invasive weed species that threatens to take over the marshes and must be controlled, mostly with fires.

And new buildings are sprouting up around the headquarters complex for other wildlife managers, a fact that seems to almost perplex Bachman, who is not used to so much activity.

Ogden Bay uses are changing as well. The area has become a year-round place for birders, dog walkers, mountain bikers, dog trainers and nonhunters. Angler numbers have increased dramatically as the mouth of the Weber River has produced big catfish, large tiger musky, 6-pound largemouth bass and some huge channel cats in recent years.

Surprisingly, many people who live next to this wildlife treasure don't know it exists.

Bob Hicks of Hooper, a retired military man, has traveled extensively and learned to hunt ducks as a teen in Michigan. "The quality of duck hunting meets or exceeds anything in the country, and I've hunted in Texas, Arkansas and the Great Lakes," he said. "People don't realize how good they've got it when it comes to waterfowl hunting."

Indeed, the area might be better known nationally and internationally than it is locally.

Bob Hicks of West Haven, out to test his boat a few weeks before the opening of waterfowl season, appreciates the fact that the big area is so close to town. He can drive out and enjoy the sights of the morning, even on days when the ducks aren't flying.

In a reflective moment, Bachman talked about the things he has seen in this wild area that have made an impression.

"I've shot hundreds of ducks and pheasants, but that isn't what I remember," said the man who still enjoys hunting and training his wired-haired pointers, but not as much as he once did.

He tells about watching a peregrine falcon hunt for the first time and being amazed at its proficiency. He was shocked about how skilled the big bald eagles are at finding food.

Then there was the time he was working adjusting water when a lightning storm came of out of the west. He watched in amazement as hundreds of thousands of phalaropes balled up in a reaction to lightning.

Mostly, though, Bachman is proud of the work he has done to bring water and life in a place where he can plan, execute and finish projects to benefit the wild creatures that rely on the wetlands of Ogden Bay and the surrounding area for their very survival.