This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

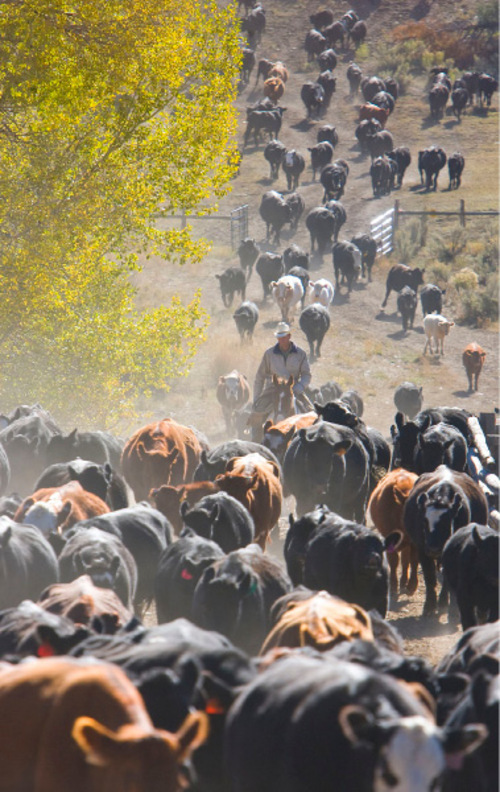

Diamond Fork Canyon • Motorists driving along the Diamond Fork cutoff got into an unusual traffic jam Thursday in a scene straight out of Utah's pioneer days.

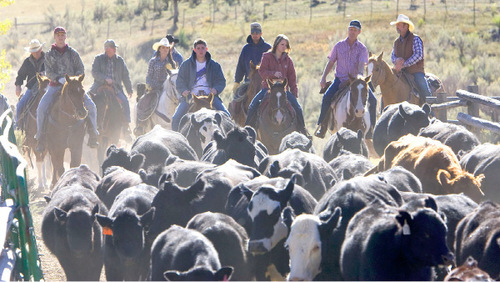

Lorelie Andrus and Amy Sanford got caught in the traffic tie-up near Highway 6 that left small children in their car squealing with delight. They found themselves in the middle of a modern-day cattle drive, complete with cowboys — and a few cowgirls — keeping some 515 calves, cows and bulls moving down the canyon.

"This is such a beautiful sight," Andrus said as cattle passed her minivan on the way to a corral near the mouth of Spanish Fork Canyon. With red and gold fall foliage as a backdrop, the cattle were driven off the mountain, cows bellowing for calves that got separated from the herd.

Members of the Diamond Fork Grazing Association were performing an annual ritual that has been repeated across two centuries: moving cattle from summer to winter pasture.

The association's members pay $2.50 per head to graze on U.S. Forest Service land in the canyon. Association members also pay for two full-time cowboys to tend the animals during the summer, with each member contributing one day in the saddle for every 10 animals they own.

Each year, about June 14, the cattle are moved up to the mountain, coming down by the middle of October before the snow falls.

For many of the association members, it's a pattern they've followed all their lives.

"I'm the third generation [ranching in Diamond Fork]," said J. Ross Nielsen, one of the association's elder statesmen, "and I've got two beneath me."

Nielsen said the cattle drives once went straight down U.S. Highway 6 to a corral in Spanish Fork, where the animals were sorted.

Today, the road is a major thoroughfare, forcing cattle to the shoulder and a path along the highway.

"There were more cattle traveling up Highway 6 than any other highway in the nation," Reed Christmas, another longtime association member, recalled.

Encroaching development also has pushed the corral higher up the canyon.

While many city folk may associate cattle with more isolated areas, the Wasatch Front sports an active cattle industry.

Terry Menlove, director of the state Division of Animal Industry, said there are about 100,000 cattle kept from Ogden to Spanish Fork.

Kim and Mont Williams say keeping cattle on the Forest Service land is good for the cattle and the land.

By free-ranging, the cattle are fed inexpensively, and do not risk epidemics of pneumonia or other illnesses that sweep a cramped feedlot.

Plus, the cattle help control wildfires by reducing the amount of fuel on the mountainsides.

Unlike most of the hands on the drive, Kim Williams wasn't born into it. She married a cattleman. For her, it was a chance to fulfill a lifelong dream.

"This is always what I wanted to do," she said, decked out in a cowboy hat, checkered shirt, jeans, leather chaps and large belt buckle.