This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Sulaymaniyah, Iraq • Construction cranes, dozens upon dozens of them, stand over this city in defiance of the past, stretching across the skyline as if reaching for the future.

And here, in the mountains of northern Iraq, that future seems as bright as the golden sun emblazoned on the ubiquitous flag of Kurdistan.

Cement trucks rumble over crowded freeways. Hip-hop music thumps from cars and clubs in the city's secular heart. In nearby Erbil, a diverse government rules over a region that is safe, stable and increasingly prosperous.

On the map, of course, this is all part of Iraq — a nation entrenched in sectarian violence, stymied by corruption and mired in political impasse.

But as the United States withdraws its forces from the country it invaded in 2003, those seeking validation of President George W. Bush's vision for the Middle East might well look to this 15,000-square-mile region bordering Syria, Turkey and Iran. The mostly autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government has many of the characteristics Bush coveted for all of Iraq when he ordered the overthrow of Saddam Hussein's regime:

It is a functioning democracy in the heart of the Middle East. It is a secular government in a majority Muslim nation. And it is an anti-terror ally in a region plagued by religious extremism.

The future of greater Iraq may be an open question, but from the Kurdish north, one thing seems clear: This is the war America won — inadvertent as that victory may have been.

—

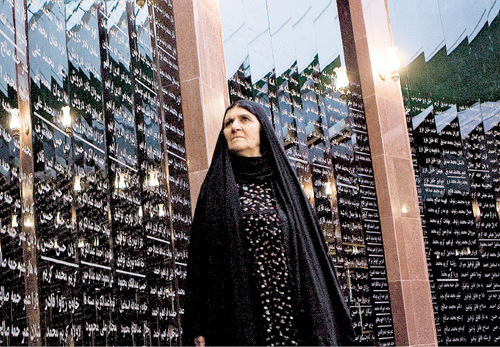

As the world watched • The wood-framed photographs lining the walls of the Monument of Halabja Martyrs are hung at an angle, as though someone lifted the 100-foot-tall cenotaph and shook it sharply to the right.

It's overkill: The crooked images are offsetting enough. Mutilated faces. Blisters and pus. Peeling skin, rotting flesh. Children — so many dead children.

This is what Saddam Hussein did to crush a Kurdish rebellion. As many as 5,000 people were killed in the March 16, 1988, massacre, the largest-ever chemical weapons attack against a civilian population.

"I returned home the day after the attack," remembered Halabja carpenter Fateh Abdul. "My father, my mother, my sister — they were all dead. All I could do to help was to bury them."

Bush later cited Halabja in justifying the overthrow of Saddam's Baathist regime. But immediately after the massacre, the U.S. — which had supported Saddam during his eight-year war against Iran — stood by. State Department officials even suggested Iran shared responsibility for the slaughter, a contention that was never backed by evidence.

During the following months, Saddam would take the indifference of his most powerful ally for a sadistic joyride. By the end of 1988, thousands of Kurdish villages had been destroyed and more than 100,000 people had been killed.

"We saw the photographers, the people with the television cameras," said Runa Ahmed, whose son died in the Halabja attack. "We believed that the rest of the world would come to save us. We waited and waited."

—

From indifference to independence • America's political leaders would come to rue the relationship they'd long maintained with Iraq's murderous dictator.

By the time Saddam ordered the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, then-President George H.W. Bush had completed a 180-degree turn on the man he'd once backed. After a swift victory in Kuwait, Bush took to the airwaves calling for the people of Iraq to rise up against their leader.

The Kurds did just that — taking control of many of northern Iraq's largest cities. Once again, Saddam responded with brute force.

Millions of Kurds fled north, sparking a humanitarian crisis along Turkey's southern border. Finally, acting on a U.N. resolution that called for Saddam to end the repression of those in his nation, the U.S. stepped in, establishing a no-fly zone at the 36th Parallel to defend the Kurds.

Saddam's forces made one more incursion into Kurdistan, in 1996 — an action swiftly answered by an American bombing campaign that further decimated Iraq's military.

By the time Saddam was deposed in 2003, the Kurds had been self-governing for years.

Today, there are few if any places in the Middle East in which Americans will receive a warmer reception than in Iraqi Kurdistan.

"If not for the support of the United States, I would still be fighting in those mountains over there," said Gen. Salah Adin as he gestured toward the rugged Zagros range, where he spent several decades of his life as part of a guerilla movement aimed at Kurdish independence.

Still, he noted, gazing across the foothills with a look of exhaustion on his face, "it was a very long fight."

—

The kingmakers of Iraq • Long marginalized and victimized, the Kurds now stand to become political kingmakers in a parliamentary stalemate that has left Iraq without a functioning government for the past seven months. If the nation survives, the Kurds may surface with a favorable share of the contested oil resources near the northern city of Kirkuk. And even if Iraq were to crumble, the Kurds would be well-positioned to claim an independent state.

That's as close to a no-lose situation as you'll find anywhere in the Middle East — and it's all thanks to a level of security unmatched in the rest of Iraq.

"The terrorists do not attack here," said Mala Baxtiar, a key leader in the powerful Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. "They try, but they do not succeed."

It's been two years since the last major attack in Kurdistan, a bombing at the Sulaymaniyah Palace Hotel that left one person dead and 30 others injured. Late last month, a suicide bomber attacked a checkpoint near Qalat-Deza, near the Iranian border, but U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers briefed on the attack say that Kurdish security forces identified the man as a potential threat early and confronted him before he arrived in any population centers. Two police officers were wounded in the ensuing explosion, but the only person to die was the man who wore the bomb.

—

Security and posterity • Government officials say security has fueled a decade of expansion in Sulaymaniyah, where an influx of Kurds seeking haven from Iraq's most dangerous regions has created one of the world's fastest growing cities. Kurdish leaders dream of an even better future.

"What we want," said Zaneh Mohamad Saleh, Sulaymaniyah's deputy mayor for public services, "is to be the Taiwan of Southwest Asia."

Taiwan has long maintained independent and democratic standing, even as China has steadfastly claimed the small island province as its own. Short of an independent Kurdistan — still the official and unanimous objective of all of the most powerful Kurdish political parties — that is the detached relationship many Kurds would like to have with Baghdad.

There are plenty of obstacles.

Kurdish journalists complain of interference and intimidation by government officials and political parties. Recently, journalist Sardasht Osman was slain after the publication of a satirical article in which he mocked the wealth, power and alleged nepotism of Kurdish region president Massoud Barzani. Barzani's government has denied involvement in the killing, but press watchdog groups derided the Barzani-ordered investigation as deficient.

Meanwhile, the government has struggled to balance the free market with the public good. A hotel fire that claimed 40 lives this past summer left the government scrambling to explain why it was not enforcing basic building safety laws and sparked an ambitious effort to upgrade hotels but not other aging buildings.

Unemployment is rampant. Immigrants from other parts of Iraq say they are abused and exploited. Women are often treated as property.

But when he laid out his plan for Iraq, George W. Bush didn't promise perfection. Rather, he pledged to give Iraqis the chance to approach the future, free of fear.

If that promise has been fulfilled anywhere in Iraq, it is here.

About 50,000 U.S. troops remain as "advisers" in Iraq, but just a few hundred have lingered in the area governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government. Those who remain help advise on border-protection issues and act as liaisons to the Peshmerga, the well-organized Kurdish militia that provides security in this region. One Army Special Forces unit near Sulaymaniyah is as likely to show up for duty in suits and ties as fatigues and helmets.

Saleh and other government officials say they believe the three-province Kurdish region is now able to stand without U.S. support. But they have not forgotten their history. As the rest of Iraq teeters near collapse and as neighboring states distrustfully eye this de facto Kurdish nation, they are wary.

"If we find ourselves in trouble, we do not want to be forgotten once again," Saleh said.

Old enemies joining forces in Iraq

Their uniforms are crisply pressed, their faces freshly shaved. The steelworks of their rifles glisten with newly applied oil. And when the training lieutenant barks for their attention, they snap sharply into place.

But Gen. Salah Adin, of the Kurdish Peshmerga army, isn't impressed by military pomp and circumstance.

"These men need to go into the mountains," he says. "That is where we will learn if they are strong."

In the coming months, Iraqi military officials say, Peshmerga fighters will integrate with Iraqi units across the country, stepping in to aid a former enemy as the U.S. military steps away. Read more at http://www.sltrib.com. —

Editor's note

In his third visit to Iraq since the U.S.-led invasion of 2003, Salt Lake Tribune national security reporter Matthew D. LaPlante traveled to the northern provinces to report on the social, economic and political impact the war has had on the nation's long-victimized Kurdish population.