This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

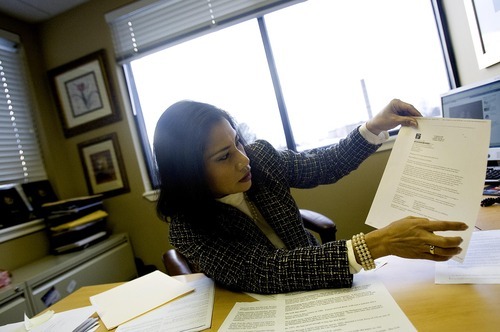

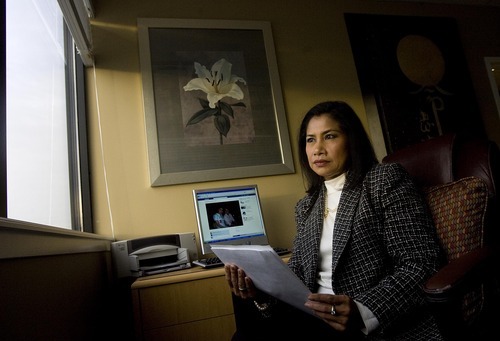

Six long years after applying to sponsor her sister for emigration from the Philippines, Cottonwood Heights real estate agent Eunice Jones was ecstatic to receive a letter last year saying the State Department finally approved her sister's eligibility.

But that didn't mean Emerald Guerra, 39, could come anytime soon. The State Department cautioned that no visas were currently available for Filipinos in her sister's category of siblings of U.S. citizens seeking to immigrate. It didn't say when they would become available.

"So we started doing some checking," said Jones, a naturalized U.S. citizen. "We found out that Filipinos who were then getting those visas had first applied in 1987" or 22 years earlier. Because of tight quotas on visas, Jones discovered that legal immigration for Guerra might require another 16 years or so of waiting.

Many Americans believe the country's laws allow for orderly immigration, and wonder why some jump the line instead of doing it legally. But the 22-year wait for Filipinos that Jones discovered may show the system is broken.

"I called immigration attorneys. I wrote to Sen. Orrin Hatch ... I was told there is nothing that can be done. I was told that is just how our system works. My mother [age 85] probably won't live long enough to see her youngest daughter come here," Jones lamented, adding that her mother's health also doesn't allow her to travel to the Philippines.

"My sister also applied four times for a tourist visa to come here, and was denied every time. They said that because she is single, there was too much chance she would just marry someone and stay here," Jones said. "This is what happens to us who try to play by the rules, while those who cheat the system enjoy benefits."

—

Legal versus illegal immigration • An out-of-work Mexican could come illegally and arrive immediately — or do it legally, and wait. And wait. And wait. Some Mexicans arriving legally now first applied 18 years ago, according to the State Department.

Worse, some Mexicans — those without much education, work skills or relatives already in America legally — probably could never immigrate legally under current laws.

"Do we have law breakers, or do we have broken laws? I'd say that most immigration attorneys would say that we have broken laws," said attorney Roger Tsai, president of the Utah chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

To show how backlogged immigration is, the State Department reported last month that 4.6 million people worldwide had applied for family-related visas to immigrate to the United States — but quotas allow only 226,000 to come each year.

At that rate, it would take at least 20 years to accommodate them all — or perhaps much longer because of bottlenecks in additional country-by-country quotas.

"We have laws that have not been changed or updated in two decades," and old quotas may be unduly choking the system, Tsai said. In fact, about 90,000 Mexicans are legally admitted to the United States annually, while 300,000 to 500,000 come illegally.

Current immigration law and its quotas give an edge to those with family connections in the United States, or those who have advanced education or wealth. But a look at how long the wait is even for those favored populations may show why so many choose to come illegally instead.

The luckiest, under current law, are the spouses, minor children and parents of adult U.S. citizens. The federal government sets no quotas for them, so their immigration is relatively fast. Jones used that advantage to help her mother emigrate from the Philippines once she herself had gained citizenship.

But Tsai said even such parents, spouses and children of citizens require eight months to a year to work through that process "to verify they are actually married and that it is legitimate." Because tourist visas last only six months, many of those people are required at some point to return to their home countries or stay for a time illegally in the country before receiving green cards.

Extra hurdles appear in that group for undocumented residents who are parents of U.S.-born children who became automatic citizens.

Those children cannot sponsor their parents until they turn 21. Even then, sponsorship is hindered by other laws that ban immigrants who have been here illegally for a year or more from legally entering America for 10 years.

—

Quotas • Unlike citizens, legal permanent residents — with green cards — cannot automatically bring in their spouses, minor children and parents because of quotas. More than 913,000 such people had applied for visas as of last month, but quotas allowed only 144,200 a year to come.

State Department documents released this month said some such people now being admitted from Mexico first applied for entry 18 years ago.

Quotas are also set for other types of relatives of U.S. citizens, including their siblings (and their families) and adult children (and their families). As part of those quotas, each individual country is limited on how many people in that category may immigrate each year.

"A lot of people ask about illegal immigrants, 'Why don't you just go back to your country? Why don't you do this the right way?' " Tsai said."Well, these wait times we're talking about are long, obviously."

In addition to giving some advantage to family ties, immigration laws also favor people with advanced education, wealth or job skills that are in high demand.

The top category for employment-based immigration is "for people like Nobel laureates or multinational executives," Tsai said. They currently have no backlog, and immigration is relatively immediate.

The second-priority category is for "those with graduate degrees," Tsai said. Here, there are backlogs of up to four years for some countries such as China and India.

The third-priority employment category is for people with bachelor's degrees, who face backlogs of up to nine years for Mexico or eight years for India. Every other type of worker sponsored by a company falls into a fourth category — and waits are up to nine years for those from Mexico and eight for those from India.

"How many fast-food restaurants are going to wait that long or are going to sponsor someone for a process that long?" Tsai asked.

Jones had thought, for example, that her sister — a dentist studying to become an orthodontist —might have better luck by applying for an employment-based immigration visa than as a sibling of a citizen.

"It only helps if you are in a field where there is a lot of demand. We found that there are a lot of dentists and orthodontists here, so there is no demand for more — so we found it wouldn't help her," Jones said.

Another program is available for the wealthy who are willing to invest at least $500,000 to create 10 new permanent jobs in America. Green cards are relatively immediate for those participants.

Finally, for the poor and rich, the State Department has a "diversity lottery" every year to give 50,000 visas to people from countries that don't have a lot of immigration to the U.S. — but only one of 100 applicants wins a visa.

—

Long odds • Many who choose to immigrate illegally likely never could have had a real shot at getting into the country legally.

"Are they the son or daughter of a U.S. citizen? No. Are they brothers and sisters of adult U.S. citizens? No. Do they have college degrees? No. So they aren't qualifying under any of these categories," Tsai said.

Some programs allow workers to come temporarily to America under sponsorship by an employer, but their numbers are limited, and competition for them can be fierce. For example, about 85,000 H1B visas are available annually for people who have a bachelor's degree, or equivalent experience.

When the economy was booming in 2008, Tsai said 150,000 people applied for those 85,000 visas on the first day of availability. During the recession this year, H1Bs were still available 10 months into the year because of a lower demand for workers generally.

But Tsai said current law does not allow changing quotas for guest workers depending on demand. And because H1B visas and similar ones for agricultural workers are tied to an employer, if a worker quits or is fired he or she must leave the country immediately and cannot work for anyone else.

Despite hurdles and long waits, 6,466 people did manage to immigrate to Utah legally in 2009, according to the State Department.

Jones' sister, of course, was not one of them.

"All I would ever want for Christmas is to have my sister here," she says. "But we may have to wait another 15 years. Why?"

ldavidson@sltrib.com Immigration facts

—

The claim • The United States already has a logical, orderly system in place for legal immigration and if would-be citizens would simply follow the rules, the immigration problem would disappear.

The reality • U.S. immigration laws and regulations haven't been updated in many years and, for most, require years or decades of waiting until a request is granted. In coming months, Utah lawmakers intent on immigration reform will argue their case based sometimes on facts and sometimes on inaccurate assumptions. Starting today and continuing through Monday, The Tribune examines whether common claims made about undocumented workers match reality.

Coming Wednesday • Are undocumented immigrants flowing into Utah and the United States in unprecedented numbers?