This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Kampala, Uganda • Not long ago, A.J. Walker was the victim.

But beneath the tropical canopy of this African nation, where breathtaking natural beauty collides with Third World squalor, that changed.

A.J. became the rescuer.

The young man, who could hardly piece together sentences after being shot in the head during 2007's Trolley Square rampage, helped erect swings at Ugandan schools that had nothing more than bicycle-rim basketball hoops and dried-leaf soccer balls.

The young man, who had to relearn to read after the shooting spree that also killed his father, handed out storybooks at a remote school along the shores of Lake Victoria where children - many of whom lived in thatched-roof huts - previously had only two English titles.

The young man, who lost some vision in his right eye, gave sight to Ugandan youngsters by installing solar panels that provided their school its first-ever light bulbs so they could study at night.

"This is the stuff I want to be doing," said the 20-year-old A.J., pausing near the village of Namatu, where teachers offered Christian and Muslim prayers to thank God for the new swings. "After you help someone who really needs help, you feel lightened. You feel good knowing that it is going to benefit that person's life."

Within the thick forests of eastern Africa - where mud is mortar, ponds are drinking water and kerosene lamps are the only night lights - A.J. fulfilled his dream: Leave the comfort of his east Salt Lake City home and perform humanitarian service in a Third World country.

With the help of the Utah-based SEEE Institute, he spent three weeks building swing sets, wiring solar panels, giving away soccer balls and winning hearts in a nation that A.J. could "relate" to, at least at some level, even though he never had been there.

A.J. has witnessed killing. He has felt firsthand the grief of losing a loved one to gunfire. He knows what it's like to be shot himself. He knows the stress, pain and prayers that follow. He understands the physical and mental barriers that can last for years or even a lifetime.

Take that burden - and Trolley Square's casualty count (six dead; four wounded) - multiply it by the thousands and you get Uganda.

It's a lush land that sees thousands die every year from malaria, dysentery, tuberculosis, whooping cough, Ebola virus and AIDS. It's a nation torn by civil war and ethnic strife in which a rebel force, particularly in the north, abducted tens of thousands of girls and boys to serve in its army. Many of those "child soldiers" became sex slaves and were required to kill family members to show their loyalty. It's a country that, while growing more stable, still harbors thousands of refugees from neighboring nations.

"As a victim of violent crime, I can kind of relate to them," said A.J., who returned Thursday night. "It is just sad to hear what they have had to go through, on top of everything they are going through right now. And they don't have the help or the resources to overcome that traumatic event."

Enter A.J. and his fellow volunteers. They lifted a place too often laid low. They brought hope to a people who too often have seen despair. They brought toys and grins to young ones who too often have seen little play or laughter.

For A.J., his African excursion served as the "mission" he might never get to fill for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But his journey also proved to be a coming-of-age experience and a nagging reminder of the health problems that still plague him post-Trolley Square.

Interactive: A.J.'s travels in Uganda

Dream catcher

A.J. may have had a dream, but Tim Peters caught it.

The Engineers Without Borders volunteer stumbled upon A.J.'s ambition last February when the then-19-year-old, speaking about his future on the third anniversary of the Trolley Square attack, told The Salt Lake Tribune that he wanted to travel to Africa to do humanitarian work - perhaps to build an orphanage.

It was late when Peters read those words. But they stuck with him.

Why? Because the West Valley City man could make that dream happen. He wasn't planning to build an orphanage. But he was planning to help children in faraway Uganda, where poverty is so paralyzing that much of the population lives without running water, electricity and sewer; where not even 2,000 of the 28,000 miles of roads are paved; where typhoid fever and dysentery rage because of contaminated drinking water; where mass murder, rape and kidnapping remain not-so-distant memories of war.

So Peters - whose wife had been childhood friends with A.J.'s mom - invited the young Trolley Square survivor to accompany him to eastern Africa with the SEEE Institute.

"All you need is a heart to help these people," Peters said. "That's what I saw with A.J. He had a true desire to help other people."

Outside a tiny school in southern Uganda's Kiwumpa, A.J. mused that his "desire" didn't come with the same engineering smarts as his tech-savvy companions. He had never built swings. Never assembled solar arrays. Never been to Africa.

That didn't matter.

A.J. didn't need that know-how to reach the people he most wanted to help: the children.

Through a child's eyes

The school was empty.

With the kids out for the holidays, the classrooms of the St. John Bosco Namwabula View Primary School in Katosi-Luganzi were nothing more than wood planks and dirt floors.

The names of numbers - one, two, three and so on - were carved into one classroom wall, while painted handprints decorated another.

Outside, on a playing field overlooking Lake Victoria, a tire rim dangled from a tree, doubling as a makeshift school bell.

But no students were around to witness the work taking place - at least, not for the first five minutes.

Volunteers had hardly dropped the metal pipes for a swing set into the red African dirt when a handful of children crept from the palms surrounding the school. The youngsters - some barefooted and others rolling a tire - watched from the shadows, then ventured closer.

Although the swing set had caught the children's attention, A.J. soon became the center of it. A tot with fuzzy pigtails and a peach dress raised her arms to be held. Another girl clasped A.J.'s hand for a thumb war. A curious teen tried to mimic A.J's Vulcan "V" with his fingers.

It wasn't the first time - or the last - that A.J. became the main attraction.

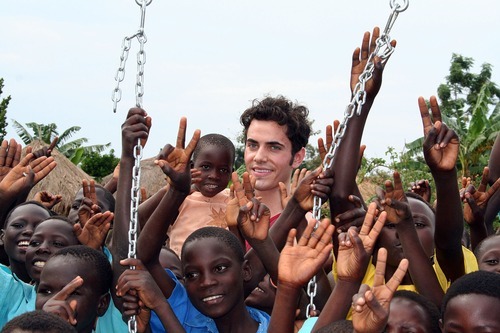

In Namatu, kids gathered around him in such numbers that only his head appeared above a sea of faces and hands. He laughed aloud, somewhat overwhelmed by the masses of children who moments before had waved furiously and tapped on the windows as soon as his van arrived.

At one point, A.J. ran, pursued by ripples of teal and orange and yellow uniforms. When the students surrounded him again, an out-of-breath A.J. flashed a peace sign.

"Peace," he called out.

"Peace," they echoed, copying the gesture.

"Snap," A.J. piped, snapping his fingers with both hands.

"Snap," they chanted, trying to mimic their mentor.

"Pound it," A.J. said, reaching his fist out over the group.

"Pound it," they replied, meeting his knuckles with a flurry of fist bumps.

In Kiwumpa, more children followed A.J. in a spirited rendition of "Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes," touching their eyes, ears, mouths and noses in a classroom so small that the Utahn could have stretched out his arms and nearly touched both walls.

The students then offered A.J. some songs of their own - some in English, others in their native tongue - including a hip-shaking ditty about visiting the zoo.

"I like kids," A.J. said. "They have all just swarmed around me. I feel I can relate to them."

And so A.J. found his niche. He ended up toting around those tots at the Katosi-Luganzi school while his fellow volunteers planted the swings - something altogether new to the youngsters at St. John Bosco Namwabula View Primary School.

The swings marked the school's second piece of play equipment. The first? A dirt basketball court consisting of bicycle rims fastened to the top of two wooden poles (without backboards).

"This is an experience [the kids] have never had," said Moses Kairigi, director of the Hope Children's Center in Namafuma. His school received a swing set during an earlier visit by SEEE Institute volunteers, the first of its kind in his county. "To the kids, that is a big thing."

A mountain to climb

As much as A.J. might have related to Uganda's children, his journey into the heart of Africa represented a coming of age for the Trolley survivor.

It wasn't long ago that A.J. had to lean on his mother to learn - again - how to read, write and speak after the shopping mall shooting. His father was gone. Jeffrey Walker had been gunned down that winter night at Trolley Square.

But Uganda was different. He decided to leave his mom, Vickie, largely out of the prep work. (He turned, instead, to Peters.)

There were practical reasons.

"As much as she would like to say she is, she is not an outdoors girl," A.J. mused.

But there were personal ones, too.

"I'm at the age that I need to be independent and do things on my own," he said. "This is a trip for me. This was one of my dreams, and I'm making it happen."

Indeed, Vickie Walker saw an independent streak arise in her son this year, along with added maturity. When A.J. finally turned to his mother for help — with packing before leaving — he penned a thank-you note and left it on her desk.

Vickie cried that night.

"A.J. is trying to forge his way," she said. "There are many cultures that have coming-of-age rituals. This was definitely A.J.'s. This was the mountain he chose to climb. And he has done it."

That "coming of age" continued overseas.

In the small fishing town of Katosi, A.J. spent the night by himself in a guesthouse room with a hole-in-the-floor latrine, a five-gallon jug for bathing, and electricity that flickered out before midnight.

It was a potentially uncomfortable position for A.J., who had complained to Peters before the trip of spiders inside his Yalecrest home. The exterminator was coming, A.J. had told him, to get rid of those "gross" pests.

But A.J. was different in Katosi. Over a game of Uno, he asked Peters if he had any spiders in his room.

"Yeah, I think I do," Peters answered. "Do you have any?"

"Yeah, I think I do," A.J. said.

"I think you can deal with it," Peters replied.

He did. Days later, A.J. even ate stir-fried grasshoppers.

The road from Kampala

Sunrise had hardly come to eastern Africa when SEEE Institute volunteers - hoping to escape the gridlock of Kampala's traffic - rumbled along a Ugandan highway between the nation's capital and the scenic Murchison Falls National Park. It was Sunday. A mist had fallen over the forest. And A.J. was sick. His face was pale. His hand trembled. His head felt feverish.

After pausing for several minutes along the road, volunteers decided to go back to Kampala. A.J. wasn't suffering from car sickness - which would be understandable, given the rugged roads - but rather the signs of a potential seizure.

"This is what happens," A.J. apologized wearily from the middle seat of the van. "I'm sorry, you guys."

The lingering ailments of Trolley Square, it seemed, had returned.

In February 2007, Sulejman Talovic went on a shooting spree at the east Salt Lake City mall, killing five people and wounding four others before police took down the troubled teen in a gunbattle.

With Valentine's Day approaching, A.J. and his father had gone to Trolley to shop and return a shelf to Pottery Barn. They eyed a few T-shirts - Jeffrey Walker even called home to check his daughter's size - but ended up buying just a few shirts for A.J.

The burst of bullets came minutes later as then-16-year-old A.J. and his 52-year-old dad, after stopping briefly to pick up sandwiches-to-go at Desert Edge Brewery, headed for the parking garage.

Talovic, wearing a trench coat, confronted them with a shotgun and fired at close range. Jeffrey Walker was killed. A.J. was hit, but managed to escape down the garage steps, where he crouched behind parked cars for cover and prayed for peace.

A passer-by stopped and helped him.

Although A.J. survived, he was hardly unscathed. Even now - almost four years after that shotgun blast left two dozen pellets embedded in his head - he has to take medication to ward off seizures.

In Uganda, Trolley Square never returned in the form of a seizure. But the threat was real for a young man who, because of his wounds, suffered a grand mal last year while working at Mountain America Credit Union.

Still, it frustrated him.

"I don't know why this is happening," A.J. said after reaching his hotel bed in Kampala that Sunday morning. "It might be because of the lack or sleep, or ... I don't know. I definitely have to watch out for it. I have to listen to what my body is telling me."

After rising at 5 a.m. - and wrestling with sleep in other locales (such as Katosi and Iganga) where music thumped, horns honked and crowds milled about until sunrise - fatigue could have contributed to it.

No matter the cause, A.J. summed it up simply:

"This sucks."

Called to serve

The health setback revealed one of the stumbling blocks that A.J. has faced in contemplating a Mormon mission and why his journey to Africa might have been as much spiritual as humanitarian.

"I've wanted to serve a mission," A.J. said the day after falling ill. "But there are things that have held me back. The biggest one has been my health."

So A.J. found his "mission" in Africa.

"I definitely think the things I'm doing right now are like missionary work," he said. "It's kind of like a service mission - going to places that really need help and helping them."

Bill Grenney, founder of the SEEE Institute and a member of Logan's First Presbyterian Church, shared that spiritual outlook. Providing aid to Africa, the retired Utah State University professor said, is a divine work.

"Each of us should return what we can from our talents," he said, "to help people in what I feel is the brotherhood of man."

Instead of bringing an evangelical light to Africa, A.J. helped bring physical light to a southern Ugandan school, appropriately named God's Grace. Working alongside SEEE volunteers, A.J. connected rooftop solar panels to a control box inside the school.

Soon, light radiated from two 5-watt, compact fluorescent bulbs. The mud-brick building lit up like never before - as did A.J.'s eyes.

He hurried to the door and shut it.

"They are going to be so excited," he exclaimed, "when they close the door tonight and the lights go on."

The school's director, Moses Katulume, took A.J. by the hand.

"Thank you for coming," he said. "You have blessed us."

Indeed, Katulume now will have enough light to do evening lessons with the children. Before, he said, "there was nothing."

Those two light bulbs illuminated something within A.J. He found himself rattling on about return trips to Africa, about other humanitarian projects, about providing villages with HIV testing.

As A.J. sees it, his work isn't over.

"You hear in the U.S. how people in Third World countries have it really bad," he said. "But it is totally different when you are seeing it and living it. It is kind of unreal. You see how bad they need help, but they don't have the resources to get it.

"I want to go help and see what I can do," A.J. added, "even if it is really small. I definitely want to keep doing this."

That's something a Trolley gunshot can't stop.

jstettler@sltrib.com

—

Trolley Square — revisited

Armed with a 12-gauge shotgun, a .38-caliber pistol and a backpack of ammo, Sulejman Talovic strolled into the Trolley Square shopping mall in February 2007 and started shooting.

Within minutes, five shoppers were dead and four others wounded. The encounter ended almost as quickly as it had begun. Police killed the 18-year-old gunman in a burst of gunfire.

But not until five others perished — Kirsten Hinckley, 15; Vanessa Quinn, 29; Teresa Ellis, 29; Brad Frantz, 24; and A.J. Walker's dad, Jeffrey Walker, 52. —

Uganda at a glance

Capital • Kampala

Population • 31.4 million

Size • 91,135 square miles (slightly larger than Utah's 84,904 square miles)

Official language • English

Life expectancy • 49 (male), 50 (female)

Education • 54 percent complete primary school.

Adult literacy rate • 77 percent (male), 58 percent (female)

Gross domestic product (per capita) • $1,200 (compared with $46,000 in the U.S.)

Major food crops • Bananas, corn, cassava, potatoes, millet, pulses

Major cash crops • Coffee, tea, cotton, tobacco, sugar cane, cut flowers, vanilla

Transportation • 28,000 miles of roads, 1,864 miles paved

Sources: U.S. State Department, CIA See all the videos of A.J.'s trip to Uganda here:

http://bit.ly/ajsmission