This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Matthew LaPlante was scrolling through Facebook when he saw a video advertising a Harry Potter version of the popular game Pokemon Go.

"Oh my god," he thought, "I need to know about this."

As he looked at the post, though, something didn't seem quite right. Sure, it had a release date and special effects, but LaPlante wanted to check it out before sharing online. And he's glad he did: It was fake news.

"It was an elaborate hoax," he explained Wednesday during a Salt Lake Tribune panel on the topic. "The reason I got fooled is because I wanted it to be true."

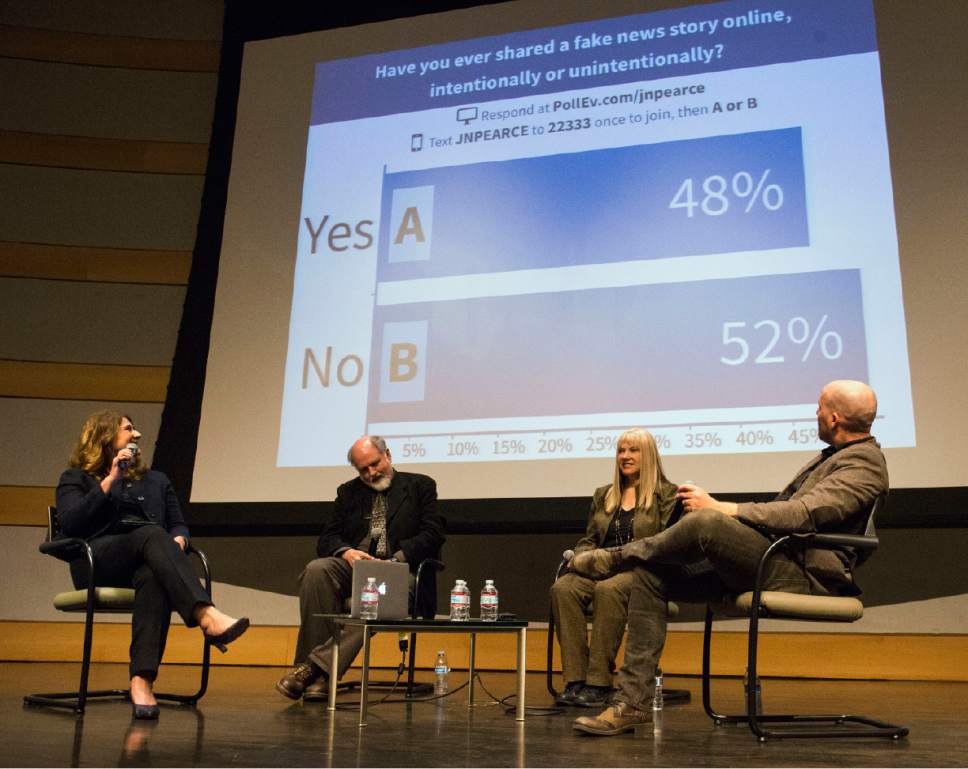

LaPlante, a Utah State University journalism professor, discussed the confusion between real news stories and false ones — like the Harry Potter game and other more political articles — during the event "Fake or Fact: What Is News?"

He was one of three panelists who spoke to an audience of about 100 people at the downtown library in Salt Lake City. The other participants — Utah Valley University professor Gae Lyn Henderson and Tribune editorial writer George Pyle — said the question of what outlets and articles to trust has taken on new prominence under President Donald Trump, who has called out mainstream media entities, including The New York Times and CNN, as "fake news" on Twitter.

It's critical to understand, Henderson said, that just because a person disagrees with a story doesn't make it false reporting.

"What they perceive as biased news, they're now calling fake news," she said.

Henderson defines actual fake news as articles a company proffers for financial or political gain that have little to no fact-checking involved in the publication process. The pieces, she said, are nearly identical to propaganda — and everyone is vulnerable to the influence and deception that has multiplied in the age of social media.

"It's a new instance of something that's been around for a long time. We used to call it a corporate press release," she said as the audience erupted in laughter.

Pyle suggested that readers have to take responsibility when consuming media online, double-checking a news story especially when it seems to confirm their biases.

"Our audiences are going to have to be just as intelligent consuming news as they are buying a car," he said.

People can generally trust established newspapers and news stations, Pyle added, because they vet facts before publishing. That doesn't mean journalists don't make mistakes, he said, particularly when they're in a hurry.

LaPlante argued that acknowledging those errors and publishing corrections is one way to ensure reliability and build trust with audiences — and one way for readers to see which companies hold a high regard for the truth.

Additionally, he said it's not a Democrat or a Republican problem: "It's been being done long before Donald Trump."

What matters, LaPlante argued, is individual complicity. Each person has a diligence to question what's presented in an article and research what's true and what's not.

"When you share lies, you're a liar," he said.

LaPlante's advice for navigating the online minefield? "Give it a moment. Do some searching. Check with some other people. Come back to it."

Twitter: @CourtneyLTanner