This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Monument Valley, Utah • The sickness in Elsie Mae Begay's family troubled her for a long time. So she turned to a Navajo medicine man.

The healer took measure of the family settlement here and told her the poison was in the dust kicked up by the wind that sometimes rips through the desert. In years to come, environmental scientists for the tribe and the U.S. government would confirm that diagnosis in their own way, saying the family was at risk from radiation left over from uranium at the Skyline Mine on the mesa above the homes.

Lately, Begay has been thinking about inviting a medicine man again — this time to bless the dirt yard at the western edge of Monument Valley. But she'll wait until the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency hauls away piles of contaminated dirt in their backyard. Then Begay wants the land finally to be healed.

"We do the Good Way ceremony," she says with an authoritative nod.

Although Begay is one of thousands of Navajo who have lived for decades with high levels of radiation in their air, land and water, she has no illusions about changing history. Instead, she holds out hope that a new generation of Navajo children won't be forced to live with uranium's dangerous legacy.

—

Cleanup • The EPA already has planned the cleanup. It is part of a multimillion-dollar campaign to tackle another round of uranium problems on the reservation.

Clancy Tenley, who is overseeing the Navajo project for EPA's Region 9, said about $22 million will be spent on building alternate water systems. EPA has also budgeted $12 million a year for five years to identify and deal with contaminated homes and mine sites.

"We recognize this is urgent and important work," says Tenley, who said his agency worked with the Navajo Nation EPA for a decade to get a handle on the problem.

About $5.9 million is being spent on the tainted piles in Begay's backyard. The contaminated dirt — as much as 30,000 cubic yards of it — is just beyond a cluster of dwellings built on land that her aunt, Mary Holiday, settled around the time the mine was idled in 1962. Begay moved her six children there in 1978 after her divorce.

One high-radiation heap lies at the bottom of the Oljato Mesa, where a long white streak points to the Skyline Mine atop the mesa. The rubble pile marks the place where steel cable lowered buckets of ore to the valley floor.

The second hot spot is a pile where ore was off-loaded from mine cars onto trucks. This spot, probably half a football field from the trailer Begay shares with two granddaughters, has the highest concentrations in the area of radium-226, a decay product of uranium.

All told, EPA investigators found 80 spots in the three-acre site where levels of penetrating gamma radiation was at least double natural background levels. And, because exposure is linked to increased risk of cancer, the EPA wants to get the radiation out.

"The goal when we get done is to get it back to where [levels were when] there was no contamination," said Jason Musante, EPA cleanup project manager. "We're trying to make it as safe as the surrounding area."

Already the two hot spots have been covered with a protective coating to keep the wind from carrying away tainted dust. The agency in November surveyed the area for archaeological artifacts and began smoothing the rough mesa-top road that will be used for hauling the contaminated dirt to a specially built landfill, where it will be sealed away from people, livestock and wildlife for good.

Musante notes that the EPA is taking a conservative approach to the cleanup. He explained that, assuming the EPA cleans the hot spots so they are no more radioactive than background levels, the area around the Skyline homes will have less than half the radiation that can be detected around Musante's neighborhood in Los Angeles.

"We try to reduce the impacts on people as much as possible," he says.

—

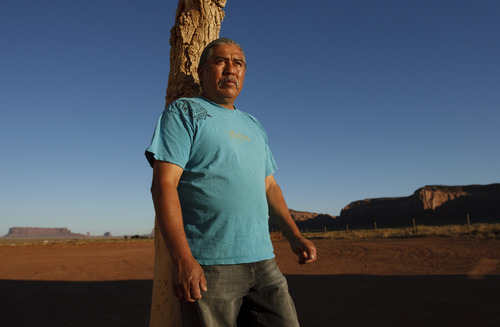

Elsie Mae • Begay, a great-grandmother at 77, might seem an unlikely heroine in the Navajo uranium story. But, in many respects, she is uniquely suited for the role because of the multiple ways uranium has touched her life.

She and her family became the face of "Every Indian" in Monument Valley films, postcards and guidebooks. They also became a kind of tourist attraction for visitors to Harry Goulding's trading post beginning in the 1920s and well into the '50s, when John Wayne and John Ford made the enchanting redrock landscape a backdrop for their Westerns.

Begay, the sister of a uranium miner, also married a uranium miner. And, when their marriage ended, she asked to live on her aunt's land below Skyline, one of more than 1,000 uranium mines, which yielded more than 4 million tons of uranium and vanadium ore that was used for atomic weapons and, later, for nuclear power plants' fuel.

She began to worry that something was wrong when the roster of dead and ill family members started growing. One son, Lewis, died from a brain tumor at age 24. Another, Leonard, succumbed to lung cancer at 42, although he never smoked or worked in the mines.

Children and adults alike suffered a long list of maladies, from asthma to arthritis to headaches and thyroid disease. The medicine man she called in blamed the family's troubles on "something gray fogging this whole area."

After Congress expanded an old coal-mine reclamation law in 1997 to include abandoned uranium mines, the EPA began looking into the radiation risk on the reservation and wound up doing its first emergency cleanup below Skyline.

Its survey had found contaminated homes and radiation hot spots all over the reservation lands, an expanse roughly the size of West Virginia in Utah, New Mexico and Arizona.

The EPA also discovered 29 water sources with higher-than-expected levels of radiation.

In 2000, EPA scientists took their Geiger counters into one of the old stone and dirt hogans below Skyline and discovered levels of penetrating gamma radiation 80 times higher than allowable limits for human exposure.

It was the eight-sided traditional home that Begay, her aunt and their children had occupied on and off for half a century.

"Even the floor, the cement was too high," Begay recalls, noting that ore rock was used in its walls and uranium-laced mortar held it together.

Though it may seem odd that the mine remnants might be used this way, it's worth pointing out that no one thought twice during the mining boom, from the 1940s through the '70s, about putting tailings dust in stucco or cutting blocks from easily shaped uranium ore. Why would they, when miners and millers worked all day in the stuff, usually without protective gear and often without ventilation?

Begay says of the hazard: "We didn't know anything about it."

In April 2001, men in white protective suits tore down the family's hogan with a backhoe, then hauled away the rubble.

But the poison remained, concentrated in the two piles between the homes and the mesa, which two generations of children used as a playground.

Frank Haycock, who used to play around the mines all over the Oljato Mesa as a kid, will be happy to see the piles go. "We didn't know it at the time that it was dangerous, that we'd get sick," he says, now married to one of Holiday's daughters and living in one of the homes below the mine.

—

Uranium • Even with the cleanup, the fight to bring attention to the uneasy relationship between the Navajo and uranium is far from over.

In the courts, advocates for the Navajo have failed to protect tribal lands from more uranium mining despite a ban enacted by the Dine Natural Resources Protection Act of 2005.

"From their perspective, why should they be victimized from another wave of uranium mining?" asked Eric Jantz, an attorney who worked on one of the cases. He adds that cases like Begay's underscore that new mining seems foolish, given how long it has taken to recognize and address the damage Navajo have suffered because of the past uranium boom.

"It seems ridiculous," he says. "People are having to wait generations to have these problems addressed."

On the public front, the Chicago-based group Groundswell Educational Films continues its campaign to bring attention to the legacy of uranium on the Navajo Reservation. Its 2000 film "The Return of Navajo Boy," which features Begay's family, is used as an educational tool to raise awareness on and off the reservation.

Now Groundswell maintains a Web and Facebook presence and helps Begay land speaking engagements nationwide. In addition to appearances and "Navajo Boy" screenings around the West, it has underwritten her travel to speaking engagements in the nation's major cities, including Los Angeles, New York, Washington, D.C., Chicago and Philadelphia.

"We want to continue to call attention to the issue because we know Elsie's not the only one affected by it," says Jeff Spitz, who founded Groundswell with his wife, Jennifer, and serves as its executive director.

In addition, Spitz has furnished Mary Helen Begay, Elsie's daughter-in-law, with a Flip video camera, which she uses to witness developments on the cleanup and other uranium issues.

A natural investigative reporter, she grills EPA cleanup honchos, contractors and other visitors, and Spitz posts the interviews on a Web page (bit.ly/eLZae9).

She wants to hold people accountable for their promises and their assurances that her family, which lives across the Oljato road from Skyline, is not at risk from the radiation. She wants to help give her family and all Navajo a voice.

"Almost everyone in the community was affected by uranium, losing loved ones," says Mary Helen. "We're just trying to get the word out, to let people know what we have been experiencing here."

—

Home • The EPA has told the people who live in the Skyline Mine settlement that they must relocate during the cleanup next year. There is no obvious place for them to go, but the EPA has promised to help.

In the end, they plan to return.

Granddaughters Melanie Begay, 21, and Shuree Fatt, 20, are also looking forward to returning to this place, the cradle of so many happy memories of growing up. In the summertime, all the cousins played in the shade of the mesa, sometimes cooking imaginary meals, sometimes mounting contests on the abandoned mine gear. During winter, they slid downhill on inner tubes toward the highway.

"I think I want to live here," says Fatt, holding her sleeping newborn, Abigail, in a traditional cradleboard.

"Obviously, 'cause we loved it so much," adds her cousin, "it'll turn out they'll love it."

Begay is fond of those memories, too. But she doubts the children understand the risk. "They don't know anything about what uranium will do to them."

And, although she has already lost so much, she sees the cleanup as an important step forward in healing. She's already thinking about all the cooking that will need to be done for the Good Way ceremony, how they will take out the good plates and sprinkle the afflicted landscape with their wash water to help cleanse the soil.

The ceremony, Begay says, is for the times when there's pain anywhere in your mind.

"Then after that, your mind is — you think clear, you are healthy, strong again."

Cleaning up the uranium legacy

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is about halfway through its five-year program to address historic contamination from uranium mining on the Navajo Reservation, which includes the southeastern corner of Utah. Mining took place on the reservation from 1944 to 1986, and mine operators removed nearly 4 million tons of uranium ore from more than 2,000 mines.

Progress so far includes:

Screenings of 197 abandoned uranium mines. An additional 134 site surveys should be completed by spring. All 520 abandoned mines will have been reviewed by the end of 2011.

Sampling at 235 unregulated water sources. Too much uranium was found in 27 of them.

Plans to spend $22 million to build water systems for homes near eight contaminated water sources and another program to serve 3,000 homes.

Checking out 199 structures for potential contamination. Twenty-seven structures and 10 residential yards were demolished and excavated, and seven more are scheduled for next year. Fourteen homes were rebuilt.