This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On the final day of the 2015 Utah Legislature, teachers were described as incompetent, criticized for having a poor work ethic and compared to 3-year-old children crying for more on Christmas morning.

The comments, from two freshmen lawmakers and state Superintendent Brad Smith, along with similar rhetoric offended educators, who just days earlier had rallied for increased school funding.

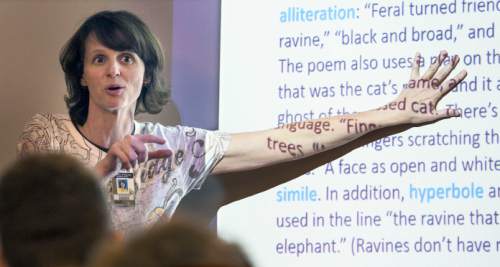

"Every teacher I know is working their guts out," said Sand Ridge Junior High English teacher Jennifer Graviet. "We're working 12-hour days. We're working after we go home."

Graviet, a 20-year veteran of Utah schools, said disrespect for teachers and second-guessing of educators aren't new or uncommon in Utah's conservative Legislature. But she said the candor and "insults hurled" this session surprised her.

"Maybe it's my imagination, but this year seemed especially — I don't know — vitriolic, I guess; hateful."

The comments were triggered by SB235, a proposal by Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, R-Sandy, to identify failing schools and hire outside consultants to work with local administrators.

The bill, approved on the final day of debate, costs $8 million and uses as its measuring stick the state's school-grading program, which itself is based on year-end test scores.

Teachers say the bill is punitive and inappropriately turns to noneducators for classroom solutions. And the debate, they say, hints at the ever-growing target placed on school employees.

"There's a constant barrage of negative things about teachers," Centerville Junior High English teacher Joanne Day said. "If we want to get higher-quality teachers, we need to make this job more desirable, and it's just going the opposite direction."

Utah's teachers are overwhelmingly female. In 2012, there were three women in Utah classrooms for every man, according to Utah State Office of Education data.

That gender disparity contributes to how Utahns discuss education, Graviet said. Like many traditionally female professions, she said, teachers are underpaid and not viewed as career professionals.

"A lot of people," she said, "view education as a secondary income or a temporary job."

Smith said his "Christmas morning" comment, made during an interview with The Salt Lake Tribune, was "unfortunate" and the result of a lack of discipline.

He said the message lost during debate on SB235 is that the public school system, not public school personnel, is failing Utah's most at-risk students.

"It is so tempting when you're looking at something like this to engage in the rhetoric of failure," he said. "That does not mean that we have adults who don't care. That does not mean that we have adults who are lazy or have inadequate work ethic or anything else. It means that we have not addressed systemic aspects of what we're doing with children in a way that allows us to meet their needs."

—

A history of mistrust • Smith was selected in October to head the state Office of Education, a position often viewed as Utah's primary advocate for public schools. To many teachers, his "Christmas morning" comment was like a captain fleeing the ship.

"We're supposed to be on the same team," Graviet said. "Why would he not want us to have resources?"

But Smith's comparison wasn't made in a vacuum. North Ogden Republican Rep. Justin Fawson raised eyebrows during caucus discussion of SB235 when he said the message he gets from educator groups is they're incompetent and need funding to become competent.

West Jordan Republican Rep. Kim Coleman said that, unlike private-sector workers, who are motivated to do "Google searches" and stay competitive, teachers expect job security if their performance is mediocre.

"There is not that concern," she said. "There's not that fear or consideration."

Fawson declined an interview. But he wrote in an email that his comments were meant to highlight the difference between incentivizing high performance and correcting low performance.

"I'm far more interested in prevention than a cure," he said, "and would strongly encourage the Legislature to look at adequately funding recruitment and retention efforts to ensure that we're hiring and retaining the most qualified teachers, counselors and administrators."

Fawson said there is a history of mistrust between lawmakers and teachers that has led to legislators taking the reins of school governance.

"I was elected to have a positive impact on education," he said. "But I was not elected to be a state or local member of the school board — which is where the decisions and accountability should rest."

Coleman also refused to participate in an interview and did not respond to questions submitted by email.

Rep. Carol Spackman Moss, D-Holladay, said the comments that came out of the Republican caucus meeting were "appalling," but not unprecedented.

Moss was first elected in 2000 — she retired from the Granite School District the next year, after three decades in the classroom — and she said the attitude of her representative in the House prompted her to run for office.

"Every time I'd read his statements, they were all negative toward teachers," she said. "I taught half of his eight children. His kids got a fabulous public education."

She said nearly all of Utah's lawmakers run on a platform of supporting schools, but then sponsor a combined 100-plus bills each year telling educators what to do and how to teach.

"It's like a split personality up here," she said.

—

Rescuing schools • In addition to SB235, lawmakers approved roughly $500 million in new funding for public and higher education, including a 4 percent bump in per-student spending and a $75 million property tax increase.

Salt Lake City Democratic Rep. Joel Briscoe, a former educator, said rhetoric shouldn't be ignored. But he suggested the votes of the majority are more important than the barbed criticisms of individuals.

"Maybe it doesn't matter," he said, "what [lawmakers] say as long as they pick the actions that benefit educators."

Briscoe objected to the late arrival of SB235, which did not allow time for a House committee hearing. And he said it relies on test scores to judge school quality, rather than tracking the progress of children.

But, he added, there was "plenty to like" in the bill, just not enough to earn his vote.

"Even though I have my concerns about SB235, that's 8 million new dollars targeted toward very specific schools that have a need for some extra help," he said. "That's not insignificant."

Niederhauser said by paying consultants, rather than giving the money directly to schools, his bill is designed to foster a new school culture and avoid reinforcing the status quo.

"If you don't change the culture and the ability of the school," he said, "putting in more money will get you the same result."

The measure also includes a reward component, offering salary and funding bonuses to failing schools that improve their school grade.

"The main message is that this is not a punitive effort," Niederhauser said. "This is a rescue effort."

For the past several years, Ogden schools have participated in a similar school-improvement program administered by the University of Virginia's Darden School of Business.

District officials credit the program with shrinking achievement gaps and boosting attendance and graduation rates. But the district also has experienced a high turnover in its teaching staff, with many educators fleeing the district's data-heavy strategies and reforms.

"I had two [teachers] that chose to leave, that wanted to seek out a different school district," Mount Ogden Junior High Principal Jessica Bennington said. "You have to come to the understanding as a leader that it's OK for people to not like the business and to move on."

Smith said it's foolish to assume schools have nothing to learn from well-run organizations such as hospitals, universities or for-profit businesses.

He said SB235 provides an opportunity for Utahns to learn from one another, and it's not an indictment of teachers to say schools need to be willing to change.

"We're public servants," he said. "The public, I think, has a right to have some expectation that we meet the needs of the children in these schools."