This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

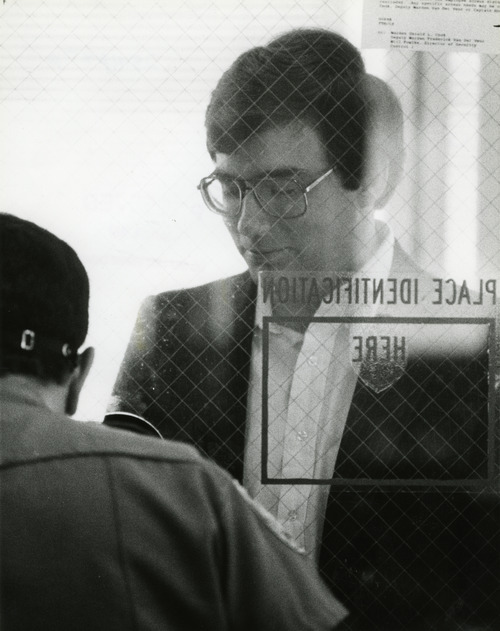

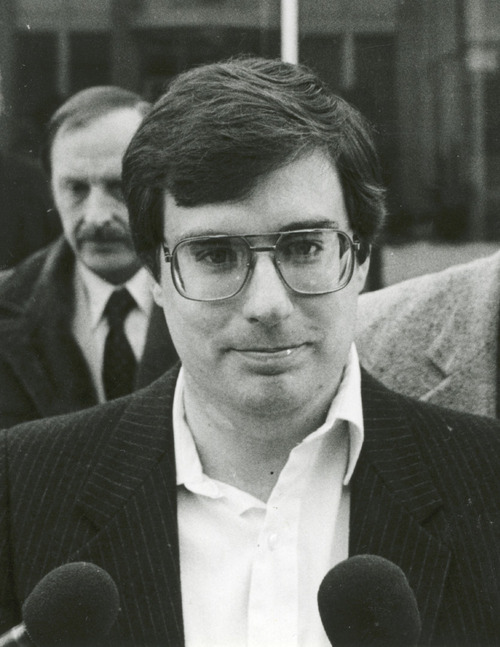

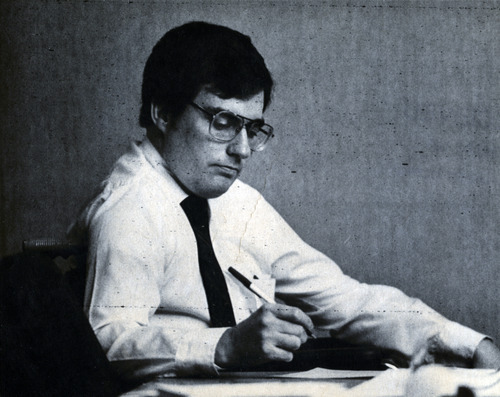

Mark Hofmann says a childhood delight in fooling others with card tricks and magic eventually led him to become a master forger and the killer of two people.

"As far back as I can remember I have liked to impress people through my deceptions," Hofmann wrote in a January 1988 letter to the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole. "Fooling people gave me a sense of power and superiority. I believe this is what led to my forging activities."

Hofmann's four-page handwritten letter — obtained Monday by The Salt Lake Tribune following a December ruling from the state Records Committee — gives new insight into the Salt Lake City man's motive for killing two people with separate pipe bombs in October 1985. Rather than face exposure as a forger, Hofmann claims he preferred to commit murder and even attempted suicide with a third bomb.

Hofmann fabricated a number of early Mormon documents designed to embarrass The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and hoped the church would pay large sums to keep them private. His infamous Salamander Letter, purportedly written by an early church convert, described LDS founder Joseph Smith conversing with a spirit that first appeared as an amphibian.

Salt Lake County investigators believe Hofmann made $800,000 in cash and $200,000 in trade for his forgeries but by the fall of 1985 had incurred half-a-million dollars in debt. He was also under financial pressure to produce a collection of letters purportedly written by a 19th-century church apostle-turned-critic.

Hofmann needed months to forge the documents, but Steven Christensen, a Mormon bishop and document collector, threatened to expose him as a fraud unless he delivered the collection by Oct. 15.

The ultimatum led Hofmann to take what he called "drastic measures" to divert attention from himself.

"The most important thing in my mind was to keep from being exposed as a fraud in front of my friends and family," Hofmann wrote. "When I say this was the most important thing I mean it literally. I felt I would rather take human life or even my own life rather than to be exposed."

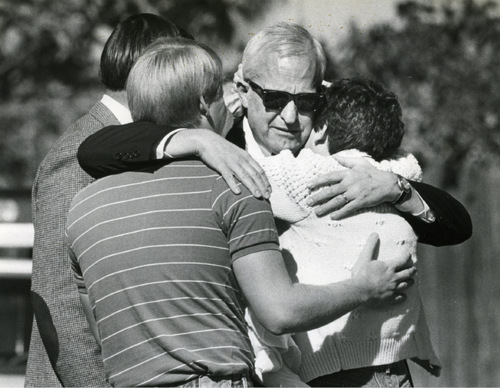

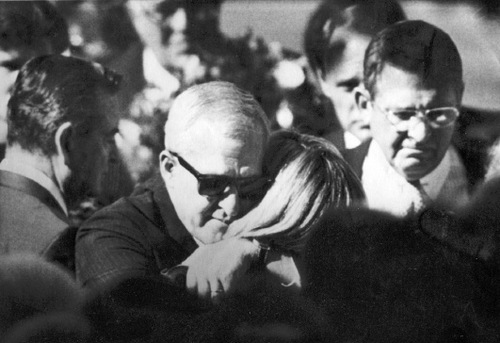

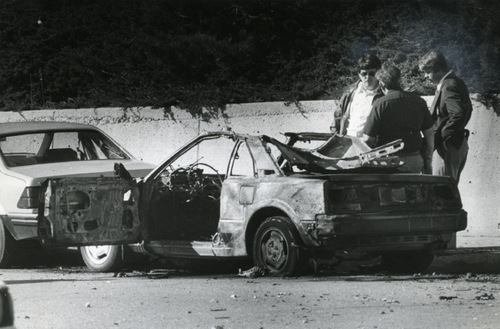

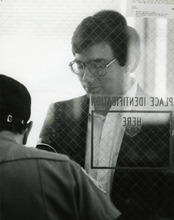

On Oct. 15, 1985, Hofmann delivered a nail-filled pipe bomb to Christensen's office. Another bomb delivered to the home of Christensen's former business associate, Gary Sheets, killed his wife, Kathleen Sheets. The next day, Hofmann, then 30, became a suspect when he was seriously injured by a third bomb that exploded in his car.

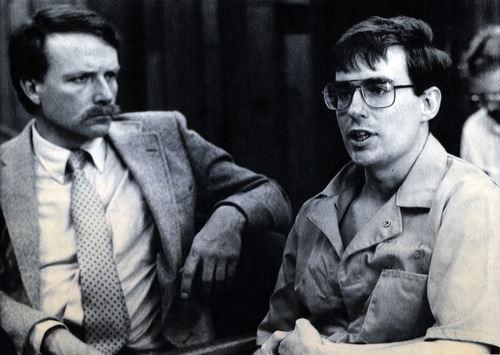

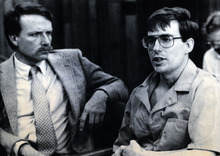

In January 1987, Hofmann pleaded guilty to two counts of aggravated murder. Hofmann avoided the death penalty by agreeing to give interviews to prosecutors that dealt mostly with his forgery techniques and his knowledge of Mormon history.

At his parole hearing a year later, Hofmann expressed no remorse for his victims and said that "toying" with people's religious beliefs was "experimentation ... to see why they believe what they do." Parole board members ordered him to spend the rest of his life in prison, without the possibility of parole. Hofmann, 56, remains housed at the Utah State Prison in Draper.

Hofmann's 1988 letter to the parole board — which has not previously been made public — begins with the line, "These are some of my thoughts concerning my crimes and how I became what I am."

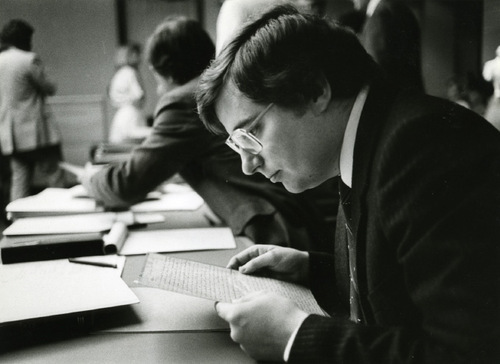

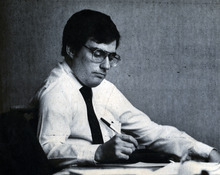

He writes that deceiving people with card tricks evolved into creating forgeries after he began collecting coins at the age of 12.

"I figured out some crude ways to fool other collectors by altering coins to make them appear more desirable," Hofmann wrote. "By the time I was 14, I had developed a forgery technique which I felt was undetectable. I exuded (sic) in impressing other collectors and dealers with my rare coins."

"Money was not the object," insisted Hofmann, who said he never sold a forgery until he was 24. By then, his interest had shifted from U.S. coins to Mormon money, which he created with the help of old ink recipes.

Hofmann wrote that a year later, at the age of 25, he "decided to forge for a living," and that forgery became "almost my exclusive source of income from 1980 to October 1985."

Under the heading "The homicides," Hofmann begins by saying, "My motives and feelings which led to the murders are hard for even me to understand, much less explain."

He writes that during what he called his "life of crime," he had "learned to live with the inherent stress, guilt and fears through rationalization and hypnosis."

But in October 1985, "it seemed like everything started to collapse around me," Hofmann wrote. "I could not come up with the money to pay off investors to keep from being exposed as a fraud."

Hofmann wrote that he bought components for the bombs a week or two before committing the murders.

"At the time I was not even sure who the victim(s) would be, only that drastic measures were called for," he wrote. "My original intention was suicide with another killing or killings as a diversion."

Hofmann wrote he employed "many forms of rationalization" to justify the impending killings.

"For example, for the first time in my life I took an interest in the obituaries," he wrote. "I believe I was trying to convince myself of the worthlessness of life and of life's unfairness. I told myself that my survival and that of my family was the most important thing."

Hofmann also told himself that his intended victims might die that day in a car accident or from a heart attack, and he thought about "the Nazi Holocaust, the earthquake in Mexico and other disasters."

The night before he killed Christensen and Sheets, Hofmann wrote that he went to his children's bedrooms, kissed them while they slept and told himself "that my plot was for their best good."

The same night, Hofmann said, he "chickened out" regarding his own suicide but decided who his victims would be and constructed two bombs.

"The Steve Christensen bomb was to take the pressure off of two fraud schemes I had involved him in," Hofmann wrote. "The Gary Sheets bomb was a pure diversion. I spent the rest of the day driving around town in a daze."

Watching the news that night, Hofmann learned he had been seen delivering the bomb to Christensen. The witness also noticed Hofmann's distinctive letter jacket and helped police produce a sketch of the killer's face.

Hofmann responded by taking his family to spend the night at his parents' home. He told them it was for their safety since his business associate had been killed.

"But actually it was because I knew from the news reports that I had become a suspect and anticipated the police knocking on the door at any minute," Hofmann wrote.

Early the next morning, Hofmann said, he drove to Logan and purchased parts for yet a third bomb — this one for himself.

"I had decided the night before after seeing the news that 'the jig was up' and that the only way to keep my family from the certain knowledge of my guilt (this time not only for fraud but murder) would be to kill myself," he wrote.

Hofmann signed his letter to the parole board with his name, followed by his prison identification number, #18186.

shunt@sltrib.com Read the PDF of Hofmann's letter • http://bit.ly/e0mqA7 —

Why now?

Choosing not to appeal a December ruling by the State Records Committee, the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole on Monday released a letter written 22 years ago by convicted bomber Mark Hofmann.

Hofmann submitted the letter to the board after his conviction with a notarized statement that he did not want the letter given to the news media. The Salt Lake Tribune asked the parole board for the letter, saying the letter is a public document regardless of Hofmann's wishes.

The parole board objected, claiming that releasing the letter would violate Hofmann's privacy and chill communication with the board in all of its cases. The board also claimed releasing the letter could pose a prison security risk, as Hofmann remains an inmate.

The State Records Committee read the letter in closed session and found "nothing that would jeopardize [a person's] life, interfere with parole, and it's not an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy," said member Scott Daniels.

The parole board had 30 days to appeal in district court.