This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It was a tough crowd, and Jim Bradley knew it.

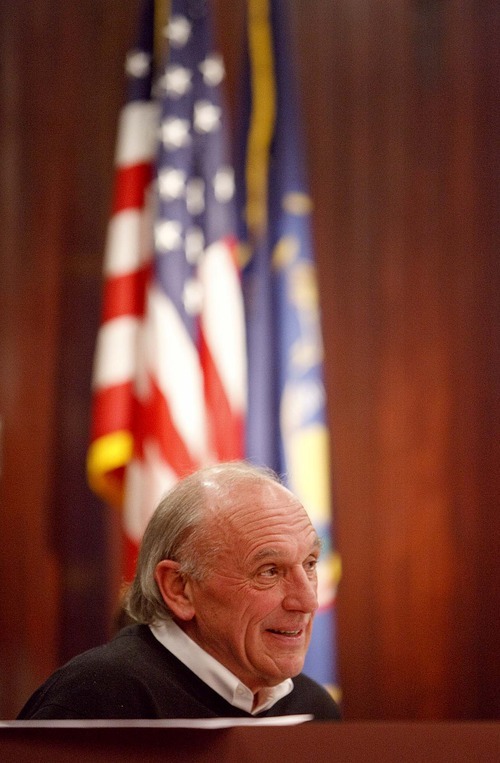

But even though the audience didn't agree with him — and even though his host had threatened a lawsuit — the Salt Lake County councilman stood before hundreds of Utah Taxpayers Association members and declared the county's unpopular police fee "the best piece of public policy that you will see in a long time."

Bradley never balks at treading on unfriendly turf.

"What is the downside?" he asks. "They can't eat you. They can do a lot of things to you, but they can't eat you."

With seeming disregard for political consequences, the longtime Democratic councilman has become the face of the county's police fee. He has defended — even when fellow council members have not — an extra charge on homes, businesses and churches to make up for a budget shortfall in policing the unincorporated county.

Some call him belligerent.

"I don't think he comes across as listening to people as much as telling them what to do," says Noel Fields, a former Magna Chamber of Commerce president who tried to convince the councilman that police fees hurt his community economically.

Others call him principled.

"He stands by what he believes in," says fellow Councilman Michael Jensen, a Republican. "You know the old line, 'If you are going to talk the talk, you've got to walk the walk'? He does it. He won't back down on principles he believes in."

—

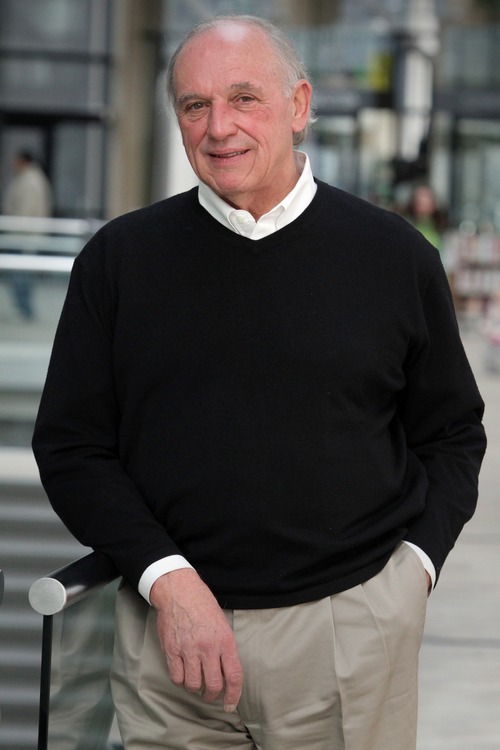

Self-image • Bradley says he's unconcerned with the politics that could cost him his job in 2012 if voters think he has done them wrong. He is convinced he has done them right.

"As much as I enjoy public service — and I truly do — if I was not elected tomorrow, it wouldn't be the end of the world," he says. "I still have a good life, a good wife, great kids and plenty of rivers to fish. I don't need this job for my ego or my income or anything else."

So Bradley, a former county commissioner and decade-long member of the County Council, speaks his mind.

Born and reared in the Salt Lake City area to an English teacher mother and university dean father, he describes himself as a product of the '60s, with political roots that formed during the Vietnam War when he protested it.

Within years of graduating from Skyline High (Class of 1964), he was on the campaign trail for U.S. Sen. Frank Moss. He later orchestrated a walk across Utah for Democrat Wayne Owens' successful bid for Congress.

Thus were the beginnings of a political career that would take him from the government trenches (once as a social services grant writer for Salt Lake County) to the top of a department (he led the Utah Energy Office under then Gov. Scott Matheson) to elected office (he became a Salt Lake County commissioner in 1991).

—

Mixed acceptance • Since then, Bradley has run unsuccessfully for Salt Lake City mayor and Utah governor, and served since 2001 on the nine-member County Council.

Sometimes people have welcomed Bradley's ideas. He created the county's urban-farming program, which is turning dozens of acres of fallow government land into planting grounds for fruits, veggies and even biofuel.

People liked that.

"It is critical that we think about our food supply and food security in the future," says Wendy Fisher, executive director of Utah Open Lands. "Jim has done a lot to spearhead this urban-farming idea and get it off the ground."

Other initiatives — such as the police fee — haven't been nearly as well received.

With its budget bare because of the recession, the county imposed a police fee on unincorporated suburbs such as Magna, Millcreek and Kearns to pay for police protection.

Plenty of people didn't like that.

Although a law-enforcement board consisting of three members — Bradley, Jensen and Mayor Peter Corroon — approved the charge, Bradley took an uncommonly active role in advocating it.

He wrote a letter that was mailed with the police bills to an estimated 46,000 property owners, explaining the reasons for the fee. He appeared on television and radio. He told reporters during Democratic Sheriff Jim Winder's re-election campaign that he was to blame for the fee, not the sheriff. And he stood before the Utah Taxpayers Association to defend the fee as one of the fairest and most transparent taxes.

Sen. Howard Stephenson, a Draper Republican and head of the business-backed association, says it would have been easier for Bradley to skip that appearance. "But he was willing to give that side. That is what public dialogue and discourse deserve."

Truth was, Bradley enjoyed the encounter.

"If you let those groups think — or if you think yourself — that you can be cowered, then to hell with them, they win. You are not going to let them win. You know you are not going to get any converts there, but you can say, 'Look, I've got something to say. I think you people are wrong.' "

—

Speaking his mind • It wasn't the first time Bradley had squared off before a hostile crowd. The same had happened in the early 1990s, when Bradley decided to rename Symphony Hall after aged conductor Maurice Abravanel. The idea proved unpopular among some symphony advocates, who thought the hall's naming rights should be sold.

So Bradley was invited to defend the idea. And he did, amid a sometimes antagonistic audience that was almost as opposed to his Abravanel Hall idea as the taxpayers association was to the police fee.

"I've always enjoyed the yin and the yang, the point and counterpoint," he says." If you sit down and explain why you are making the decision and it makes sense to them, they may not agree with you, but they will respect you. That respect comes back in aces all the time."

Fields, the former president of the Magna Chamber, sees Bradley's approach as more dictatorial than democratic, revealing a man who cares less about listening than about telling.

Not even one day had passed after Fields was named chamber president when he attended a public hearing about the police fee. He found it peculiar that the hearing was being held after the County Council had adopted a budget that factored in a police fee.

His immediate impression, which hasn't changed, is that Bradley and his colleagues "will let us talk all we want, but they have already made up their minds." Fields characterizes Bradley as "hard to deal with."

But Bradley insists that he is listening. He has supported two reductions of the fee and plans to conduct a listening tour this year with members of the county's law-enforcement board.

He believes in the fee. And he doesn't see any reason to keep quiet about it.

Having married into a family that made it big financially in the Louisiana theater business, Bradley says he doesn't need his part-time county seat and its $35,000 annual salary. Life, he says, is "very good" with or without it.

"That provides me an immense amount of freedom," he says, "to call it as I see it."

Even now, he sees the police fee as prudent policy. Everyone pays. And everyone knows what they are paying for. So when his colleagues talk about pushing for a utility tax before the Utah Legislature this year or getting rid of the fee as sales taxes recover, he remarks candidly, "it is probably a mistake."

It isn't popular. But it's what Bradley believes.

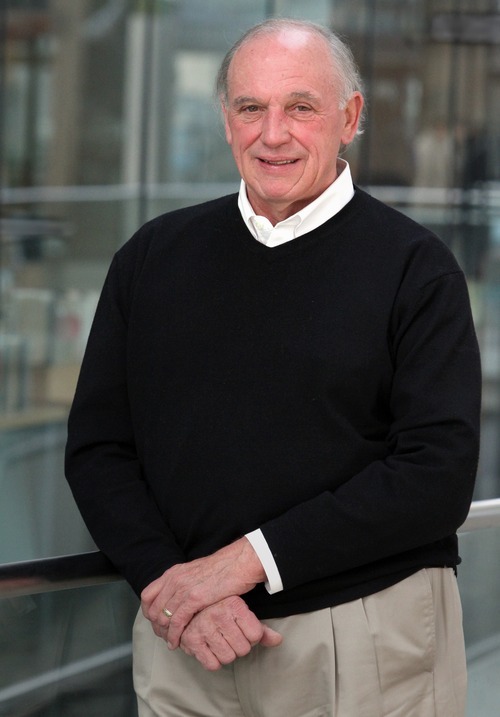

Jim Bradley

Age • 64

Family • Wife, Glenda; children, Bill (39), Elizabeth (35), Nick (18) and Zeke (16)

Education • Bachelor's degree in political science from the University of Utah

Political background • Salt Lake County councilman since 2001, former county commissioner, one-time candidate for Salt Lake City mayor and Utah governor

Recent kudos • Received the 2010 National Award for County Arts Leadership from the nonprofit Americans for the Arts —

More video links

O Hear more from Jim Bradley at the following links: