This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When Dennis Cecchini drove his grandson, Kayson, to Ogden about a week ago, the 10-year-old knew to look west on Interstate 15.

A billboard with a young blond man's face came into view. Kayson shouted with glee: "Grandpa! It's Daddy!"

This billboard — raising Utahns' awareness of the anti-overdose drug naloxone — now is the only way Kayson gets to see his father, Tennyson Cecchini. In May 2015, Tennyson died on Dennis Cecchini's bathroom floor of a drug overdose. He was 33.

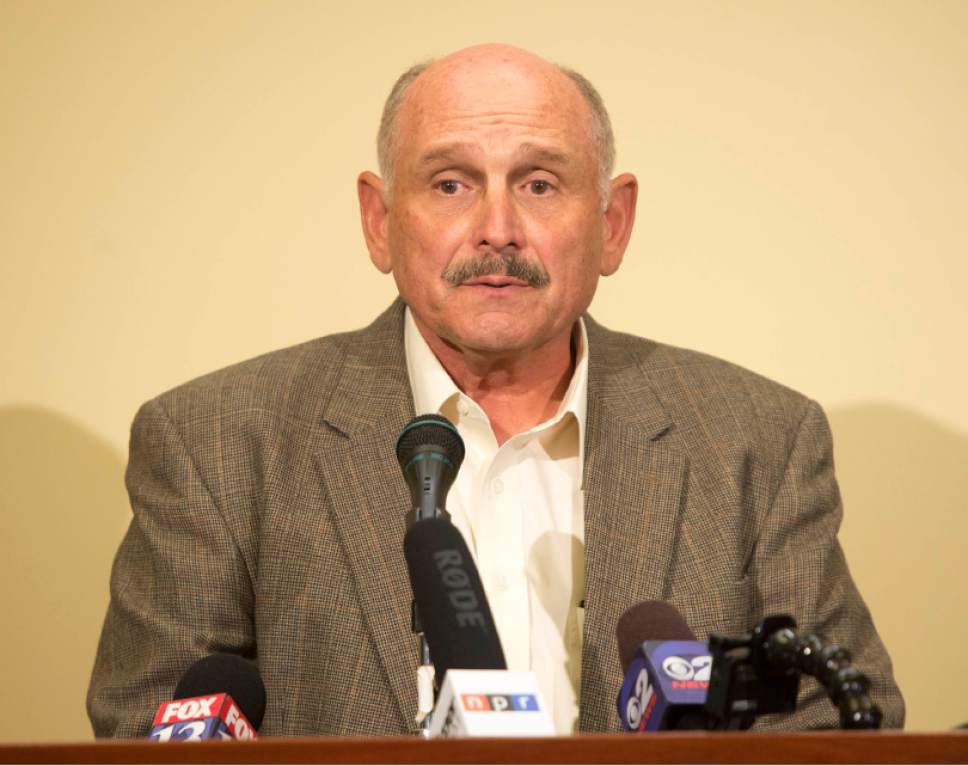

Tennyson "was starting a full life, and [addiction] stopped it cold," Cecchini said. "He lost ... everything."

Cecchini tried to get Tennyson help several times after a sports injury around 2005 led to his pain pill addiction. But treatment never worked.

It's a pattern of relapse that a recent Salt Lake Tribune-Hinckley Institute of Politics poll showed is not uncommon in Utah, a state ranked fourth in the nation for drug-overdose deaths.

Thirty-two percent of the 605 Utahns polled said they knew a person addicted to opiates. Of those respondents, 71 percent — or 138 people — said that the friend or family member sought treatment. But only 46 percent of them said the treatment was successful.

The overall poll, conducted by Dan Jones & Associates, has a margin of error of plus or minus 3.98 percentage points.

Experts attribute relapses, in part, to the many barriers that addicts and their families face when trying to get help, including the cost of treatment and lack of space in treatment facilities.

After years of battling his addiction in silence, Tennyson told his parents that he was struggling about two years before his death in 2015. They immediately started hunting for an appropriate treatment program. The task was daunting.

"We didn't know where to turn to get treatment," Cecchini said. "You get online and start looking through ads to see if anywhere might be telling the truth." Cecchini tried to get Tennyson help in a publicly funded program, but the waitlists were a month or more. And Tennyson couldn't wait that long.

So Cecchini and his wife, Celeste, dipped into some cash they had on hand. Tennyson also had insurance to help cover the cost.

Many families must navigate the choices between public and private treatment services to get their loved ones help. Though it depends on the kind of treatment needed and where an individual lives, waitlists to get into publicly funded services can be "huge," said Jeff Marrott, spokesman for the state's Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health.

"There are hundreds of places that range from outpatient all the way to inpatient hospitalization" across the state, Marrott said. "But in the public system, there are never enough providers and never enough facilitators to meet the need."

Private programs have a much larger capacity — but it comes with a price tag, Marrott said.

Though Cecchini can't recall the cost of the outpatient treatment, he vividly remembers that Tennyson relapsed while in the program — this time, turning to heroin.

It's a common jump for opioid addicts. About 80 percent of heroin users start with prescription drugs, according to the state Department of Health.

Tennyson's addiction continued to spiral out of control, Cecchini said, until they kicked him out of the house so he could "hit rock bottom."

When Tennyson finally agreed to return to treatment, Cecchini found him a private, inpatient facility in Utah County. The couple tapped inheritance Celeste received from her parents to get him in — the facility wanted $10,000 upfront — and Tennyson's insurance covered most of his stay.

After 60 days, Tennyson was told he could leave. The last bill Cecchini remembers seeing was about $45,000.

"This [cost] is part of why [our children] are dying," Cecchini said. "Somehow, we have to figure out a way to lower the cost of care and then subsidize the cost of care. If they're not in for at least six months, there's a real possibility of relapse."

And Tennyson did just that. Four days after Tennyson was released, he overdosed on his parents' bathroom floor.

Cecchini believes it might have ended differently if they could have forced Tennyson to stay in treatment past the 60 days — he suspects the insurance plan refused to cover any more care.

So this year, he helped push a measure through the state Legislature that would allow relatives to petition a court to mandate substance- use treatment for adults.

Under the measure, signed by Gov. Gary Herbert, a court can order treatment if there is "clear and convincing evidence" that individuals suffer from a substance-use disorder, are unlikely to benefit from a less-restrictive treatment or present a serious harm to themselves or others.

The petition to the court must include a financial guarantee that the petitioner or another individual will pay any costs incurred beyond what the addicted individual's insurance covers.

"We have to stop doing business as usual," Cecchini said, "because this epidemic is killing them."

astuckey@sltrib.com Twitter @alexdstuckey