This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Few, if any, of the hundreds of patients who check into the Huntsman Cancer Institute for surgery or chemotherapy will give a moment's thought to whether the hospital's medicine cabinet is stocked.

That's as it should be, says Huntsman pharmacy Director Scott Silverstein, who does the worrying for them, freeing patients to focus on healing.

But a worsening national drug shortage has Silverstein anticipating the day he has to interrupt a patient's therapy to say: "We can't deliver on a drug. We can't treat you."

He's in a privileged position. Providers across the United States are already having those conversations as drugs of choice ranging from cancer treatments to surgical sedatives run low — or run out — forcing providers to turn to less-preferred medicines.

In some cases, patients have died for want of the right drug.

Providers at the University of Utah's hospitals and clinics have been able to prepare for acute shortages either by rationing drugs, using alternatives or finding other sources.

It helps to be home to the nation's alert system, said Silverstein, referring to the U.'s Drug Information Service (UUDIS).

The service monitors and verifies shortages and reports them to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, which publishes them online. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration looks to the service to make decisions, such as whether to allow foreign imports.

And it's setting the standard for how providers can cope with a public-health problem, fueled, in part, by the toll of the recession on drugmakers' profits.

"I didn't use to have to think about whether a drug would be available," Silverstein said. "Now it's getting to the point where it's what keeps you up at night."

The numbers are unprecedented, said Erin Fox, manager of UUDIS, which has been tracking drug shortages for a decade.

Fox recorded 211 drug shortages in 2010. That's up from 166 in 2009 and 70 in 2006.

"It's like disaster management daily," said Fox, who has seen no signs of it leveling off. "We're on pace with last year. Pretty much every day, we get a new shortage."

Many of the drugs in dwindling supply are staples used every day: antibiotics, chemotherapy agents, morphine for pain relief, propofol for sedation, heparin to prevent strokes and epinephrine used in emergencies for heart attacks and allergic reactions.

About 54 percent of the shortages in 2010 were due to product quality problems, said Valerie Jensen, associate director of drug shortages for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Two of the largest manufacturers of sterile injectables, such as propofol, had product recalls last year after the FDA found particulates in the syringes.

Another 21 percent of the shortages are due to production delays, while 11 percent are caused when firms discontinue a product, usually for business reasons, Jensen said. The rest stem from increased demand, raw material shortages and the consolidation or closure of manufacturing sites.

The FDA can't force a drugmaker to ramp up production. And companies don't have to warn the agency of impending shortages unless there are no known alternatives on the market.

But a summit convened in November by the American Society of Health System Pharmacists brought providers together with regulators and drugmakers to forge solutions.

"The big thing that came out of that meeting was the need for more transparency and communication," said Michael Cohen, director of the Institute for Safe Medicine Practices [ISMP] in Horsham, Penn. "It sounds so simple. But there are times when one manufacturer closes a line, when another can pick up the slack."

The FDA has a role, too, Cohen said. With the recession, generic drugmakers started growing rapidly, but they faced limits on where they could purchase raw materials, much of which came from overseas. This caused the FDA to crack down on quality — "and rightfully so," Cohen said. "But maybe with no real understanding of the consequences."

Shouldering most of the burden are providers, he said. "The amount of time that's being taken away from patient care is phenomenal."

In an ISMP survey last summer of 1,800 health care workers, one of four said shortages led to medication errors that could have harmed patients. One in five said patients were hurt.

Doctors in some parts of the country reported having to ration cancer and other niche treatments for which there are no substitutes, deciding whether to start a new patient on a therapy or hold off to preserve the drug for someone who had already started a cycle.

"We had a few deaths with opioids," Cohen said. Lacking morphine, hospitals had to switch to the more potent Hydromorphone, which, when given at morphine-level doses, led to overdoses.

"Hospitals need a good program in place for rapidly educating staff on how to administer atypical pharmaceuticals," Cohen said. "They need secondary purchasing sources lined up, and they need a system for notifying everyone, from administrators to physicians and nurses, of impending shortages."

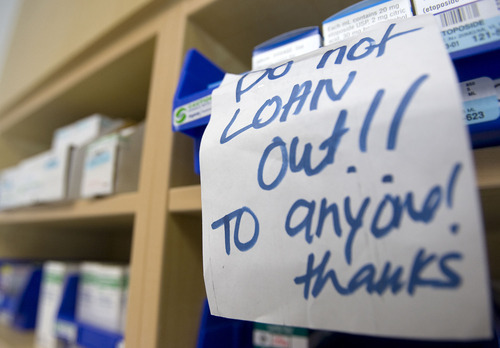

Silverstein begins each day by checking a white board, where "shortages of the day" are listed. He knows they're real — not just due to a back order with one drugmaker — because UUDIS verifies reports coming from pharmacy buyers across the country.

In this way, the system helps providers anticipate problems without them having to unnecessarily hoard pharmaceuticals.

"We have an incredible communication network with our [University of Utah] health centers," Silverstein said "Sometimes, we partner on drug buying. It often comes down to identifying how many patients are coming in on a given week. We're blessed to have a drug information center that's so proactive."