This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When artist Robert Smithson approached Utah contractor Bob Phillips with plans for what would be his masterwork, Phillips was reluctant to take the job.

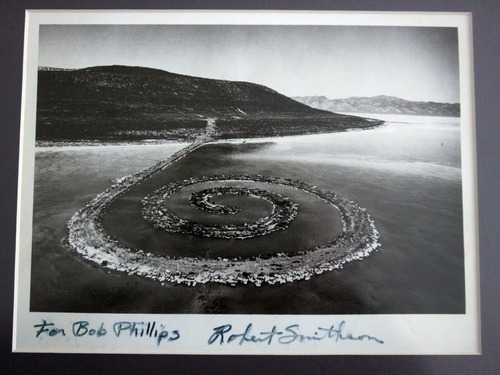

Phillips had built mineral-extraction dikes in the Great Salt Lake, but Smithson's Spiral Jetty was an entirely different kind of job.

"I didn't understand what he was trying to do," Phillips recalls of the meeting 40 years ago. "I kept trying to convince him that he had to follow contracting rules with engineers and surveying and all that kind of stuff."

Smithson, in whose monumental spiral critics would see space galaxies, snail shells and the microscopic structure of salt crystals, already had been rejected by other contractors. "He just kept saying he knew what he was doing," Phillips says.

Smithson finally wore Phillips down, and the contractor went on to help build one of the world's iconic art works. In the process, Phillips struggled to understand what Smithson was trying to express through the Spiral Jetty.

Three years after completing the work, Smithson was killed in a plane crash while scouting a location for another of his earthworks art projects in Texas.

"I never had the vocabulary to talk to him," says Phillips, now 71, remembering how the artist kept using the word "entropy." "I thought if I could understand what that word meant, I could get into his head and understand what he was trying to do."

—

Global ripples •The grip of the Spiral Jetty on the art world's imagination seems to have grown annually since the artwork re-emerged from the brine in 2002.

One sign of Smithson's impact was the exhibit "Nobody's Property," a recent show at Princeton University Art Museum exploring projects once labeled "Earth art." To mark the artwork's 40th anniversary, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts next week opens "The Smithson Effect," an exhibit tracing Smithson's influence on contemporary artists since the 1990s.

Surprisingly, Smithson's art is not well-known in the place he made famous worldwide, says Jill Dawsey, chief curator at the UMFA. "Not a lot of Utah is aware that the Jetty is here," Dawsey says. "And those that are, are not aware that it's one of the most famous works of art in the world and people come from everywhere to see it."

Smithson worked with many artistic ideas that have been profoundly influential. "His idea of entropy has been really revolutionary," she says.

Entropy is the principle that in nature, order inevitably breaks down into disorder. In a famous essay, Smithson compared it to a character from a nursery rhyme: "All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humpty Dumpty back together again." "He expected that nature would take its course and things would return to what they had before," Dawsey says.

Smithson was influenced by Utah's landscape, ecosystem, history and culture in creating the Spiral Jetty, says Hikmet Loe, a curator and art historian who teaches at Westminister College. In turn, the Jetty is changing the way Utah and the rest of the world think about their environment.

"It brings an awareness of the land," Loe says. "A myriad of ideas came spinning out of it."

Loe is finishing a book, The Spiral Jetty and Rozel Point: Rotating Through Time and Place, which is due for publication from Utah State University Press next year. "Smithson's influence is so pervasive. If he would have lived, the trajectory of what he was doing would have been incredible."

An argument could be made that the Spiral Jetty is "one of the most significant sculptures in American art history," says artist Adam Bateman, board president of the Central Utah Art Center, who will have a work in UMFA's "The Smithson Effect" exhibit.

"The Spiral Jetty is iconic and immediately recognizable Earth art," he says, noting how the Jetty and the Earth-art movement brought American sculpture to the forefront globally.

—

Beauty in basalt • Though Phillips isn't sure what the 1,500-foot-coil of black basalt rock, earth and salt crystals means, he visits the Jetty often because "it's beautiful."

"That was the only thing I ever built that it was to look at and had no purpose," he says. "It was made just to look nice."

Phillips is widely respected for his insights on the project and his impressions of the artist. He and Smithson, 30 and 31 respectively when the Jetty was built, became friends in the short time they worked together.

Several years ago, the New York-based Dia Foundation that owns Spiral Jetty asked Phillips to write an essay on his experience with Smithson.

Phillips still wonders how Smithson came upon Rozel Point, a perfect location for his earthwork. In the shallow bay, the mineral and algae concentrations made the water "Campbell Soup" red, Phillips says. A rock escarpment on the point allowed visitors to see the Spiral Jetty, even during the decades when it was submerged.

The retired contractor remembers his queasiness in putting earth-moving equipment and trucks on the treacherous crusted muck and goo of the lake under the dictatorial direction of a New York artist. "It's tricky working out on that lake," Phillips says. "There's lots of backhoes buried out there."

But Smithson never hesitated. "When we got out there, he just took over," Phillips remembers. "I don't think he had done any geology work or anything on it. He just had in his mind what it should look like."

Smithson, in hip-wader boots, laid out the spiral with rope and long stakes. He climbed the rocky ridge to the west to monitor the workers' progress on the complex double spiral. "He just had the eye for it. I assume it was the artist in him," Phillips says.

Smithson actually built two jetties at Rozel Point. The first was a simple loop with an small island at the end that, as Phillips understood it,would serve as a helicopter pad. When Phillips and the workers finished it after six days of heavy equipment work, Smithson told them, "OK, it looks good."

Then two days later, Smithson called and shocked Phillips by saying he wanted to redo the jetty. "It was as if he had drawn a line in the wrong place and wanted to erase it," Phillips says. "I didn't want to go back out there again and risk losing the equipment."

Yet Smithson talked the men into returning and "fixing" the spiral. Three days and 7,000 tons of basalt later, the Spiral Jetty as we now know it was finished. Even Phillips could see Smithson had fundamentally changed the work.

"When he got it done, instead of being a helicopter pad or a dock, it was something for the eye to see — the black rock and the red water," Phillips says. "It was beautiful. I still don't know if I understand how that could be art. But now it no longer had any utilitarian thing to do with it."

—

Entropy vs. preservation •In just two years, the Spiral Jetty was covered by rising lake water — submerged 16 feet by 1987— and could only be seen from aircraft or the top of the ridge as a salt-encrusted ghost.

When the Spiral Jetty resurfaced, beginning in 2002, it attracted a new generation of artists and triggered discussions on preservation. A proposal in 2008 by a Canadian company to drill for oil near the Spiral Jetty brought 3,000 letters of protest and was rejected by the Utah Department of Natural Resources.

Phillips believes that Smithson would have had less of a problem with oil drilling hurting the Jetty than with the well-meaning cleanup of the shore. That happened when Utah's Division of Oil, Gas and Mining in 2005 removed the hulks of trucks, trailers, an abandoned military amphibious vehicle and rusted oil-extraction equipment — the very things that drew Smithson to the site.

"He understood the lake would keep going up and down, but the Jetty would always be there," Phillips says. "It would change and stuff, but be reborn and come back."

Smithson may have embraced the changes of the Jetty as part of his concept of entropy, but Phillips recalls his first view of the finished Spiral Jetty from the ridge in 1970.

"The real sad part is that it was so much more appealing then," Phillips says. "It isn't anything like it was. When you saw that black dike going out in that red, red water. The old girl has gone gray, encrusted in salt."

UMFA's 'The Smithson Effect'

P With one of the most recognizable works of 20th-century art in its backyard, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts presents an exhibit exploring the creative influence of Robert Smithson on a generation of contemporary artists.

When • March 10-July 3

Where • UMFA, 410 Campus Center Drive, University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City

Hours • Tuesday to Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Wednesday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Saturday and Sunday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Admission • $7; seniors/youth, $5; children under 6, UMFA members, U. students, staff and faculty, free; to arrange visits for groups of 10 or more, call 801-581-3580 (24 hours in advance)

Info • 801-581-7332 or umfa.utah.edu

More • Visit umfa.utah.edu/SpiralJetty for directions to Rozel Point, information links and a time-lapse video of the drive.

Background • More information at artmuseum.princeton.edu/events/Extended_Pages/LSAT; http://www.diaart.org/sites/main/spiraljetty, and http://www.robertsmithson.com