This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

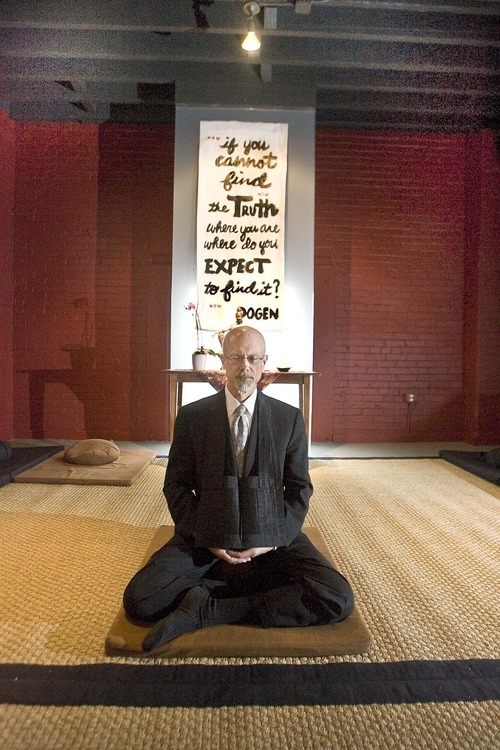

Michael Zimmerman removes his shoes and bows to the cushion on the floor before planting himself cross-legged on it.

Sitting in that way, the former chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court explains, is the primary posture of Zen Buddhism. It is the most stable position in which to rest, to empty the mind and to gain a measure of equanimity.

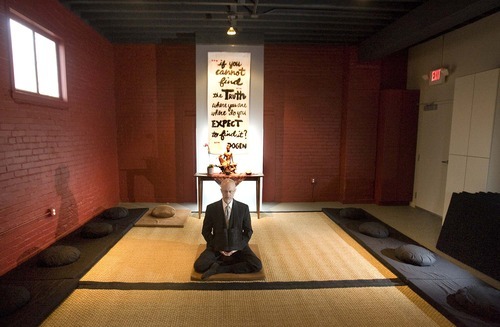

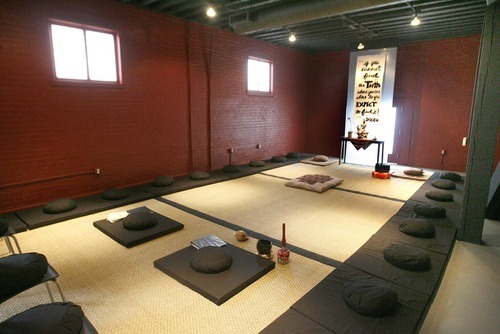

Dozens of such cushions dot the floor of the newly opened Boulder Mountain Zendo, an urban oasis at Artspace in downtown Salt Lake City founded by Zimmerman and his wife, Diane Hamilton. It is the couple's second Zen center; the first one is in Torrey, in the western portion of Wayne County.

"We are trying to reach a broad audience," says Zimmerman, who is known as Michael Mugaku Zimmerman Sensei because of titles he received after completing his Zen training. "Sometimes [Salt Lake City's] Kanzeon Center can seem too foreign to newcomers. We want to make this a nonthreatening space."

Some will come seeking only relief from stress or pain, he says. Others may want more strictly Buddhist teachings.

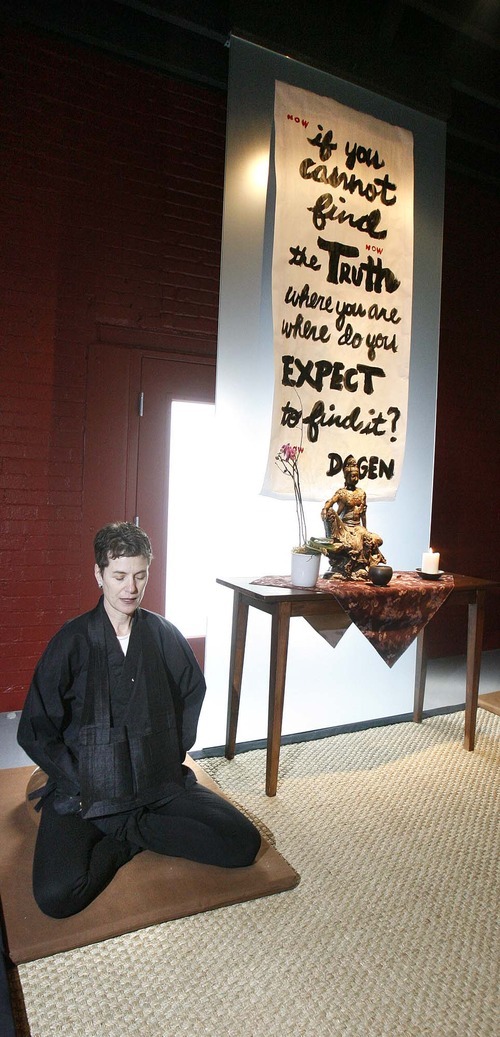

"They might also find enlightenment," says Hamilton, who goes by Diane Musho Hamilton Sensei.

Both are ordained teachers in the lineage of the late Taizan Maezumi Roshi and Genpo Roshi, who recently stepped down as a Zen priest and Kanzeon's director.

The husband-and-wife team offers a balanced approach, says Randee Levine, a Salt Lake City awareness facilitator who is delighted with the new center.

"Michael offers a more traditional Zen practice, with stability and rigor," Levine says. "Diane is an amazing group facilitator, who has a way of energizing a teaching by being deep as well as funny and completely engaging."

Anne Milliken, a longtime friend, likes the couple's "holistic look at the world."

Plus, she loves their humor. "Like a lot of people who are good at what they do, they take their work seriously, but not themselves."

Zimmerman and Hamilton each will lead several workday meditations at the Artspace Boulder Mountain center as well as direct weekly workshops and lectures.

"This is oriented to lay people and professionals to help them empty out their minds and tap into a part of themselves they don't normally reach," Hamilton says. "We want them to find an [inner] well-being that's naturally present."

If anyone needed such well-being, it was a grief-washed, overworked Zimmerman in 1994.

The future judge was reared Presbyterian (he even notched seven years of perfect attendance in Sunday school as a child), but he and his first wife, Lynne Zimmerman, attended the Episcopal Church in Utah. In 1993, cancer struck Lynne.

A neighbor suggested the couple attend a lecture by a nationally known expert on coping with pain through meditation.

His wife didn't like it, Zimmerman recalls, but he did.

After Lynne died in 1994, Zimmerman found himself scurrying back and forth between his three young daughters and his new job as chief justice. Stretched thin with pressures on all sides, Zimmerman felt like he was locked in a 3-foot-by-4-foot box.

So he tried meditating on his front porch at dawn. It brought calm before the day's whirlwind.

Eventually, the judge found his way to Zen Buddhism. It seemed so right and so helpful, he says, "like looking at the Grand Canyon or a glorious sunset. Your borders drop. Self and separateness seem to fall away."

Hamilton adds, "He was like a fish somebody let back in the water."

Before long, a friend suggested he meet Utah's new director of court-annexed alternative dispute resolution. She was once crowned Miss Rodeo Utah, he learned, and was also an expert on mediation — and a Buddhist.

He was intrigued.

Hamilton had been on her own spiritual quest for decades.

Growing up in a self-described "Jack Mormon" home in Tooele, she was troubled as a 17-year-old by the deaths of seven high school friends. She became, she says, "an existential seeker."

Hamilton was drawn to the practice of Zen because it was not about believing in the supernatural, God or gods, but about "realizing your true nature."

"It's very down to earth," she says, "and offers a perspective on all traditions and what they have in common."

The two studied together at the Kanzeon Center. In 2003, she and Zimmerman received ordination as Zen monks. Three years later, they became official Roshi successors.

They maintain that such meditation can help everyone.

"It makes you a better doctor, lawyer or journalist," Zimmerman says. "You don't cling so much to one perspective on reality. You become comfortable with ambiguity."

Several friends are eager to experience the new Boulder Mountain, especially given its proximity to a TRAX station.

"I anticipate that their center will have quite a broad palette of [Zen] colors for us," says Alan Gartrell, a friend and physician. "This East-meets-West center features two people who are teaching with everyone's best interests in mind and not an agenda."

The center probably will focus on self-exploration that is "very pragmatic, looking at ways to live with more awareness and to lessen our own suffering and the suffering around us," Gartrell says. "I hope it thrives."

The Boulder Mountain Zendo

230 S. 500 West, Suite 155

Daily practice

Monday through Friday mornings, 7 to 8:30 a.m.

Tuesday through Thursday evenings, 5:30 to 6:30 p.m.

Tuesday Dharma talk, 7:30 to 9:30 p.m.

Sunday Dharma talk, 5 to 6 p.m.

More information • http://www.bouldermountainzendo.org