This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

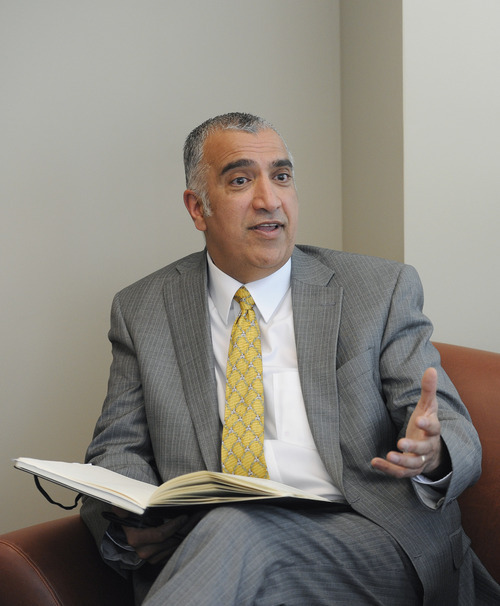

One of the first changes District Attorney Sim Gill made to his office had nothing to do with plea deals or prosecutions, policies or personnel. It had to do with water.

After just three days on the job as Salt Lake County's top prosecutor, the Democrat received an email asking if he would like to contribute to the office's water fund. He was curious, but willing.

"I thought it was a fund to collect for some charity," Gill muses, perhaps "to provide for clean water in Africa or something."

But Gill, now 100 days into his first term as D.A., discovered that the water wasn't for Africa. It was for his own office. Employees had been pooling their own money — a couple of bucks a month — to pay for water dispensers that had been trimmed out of the budget.

Dumbfounded, Gill responded that no employee should have to pay for drinking water.

"We need to treat them with respect," Gill insists, recalling that moment with a look of amused disbelief. "We need to honor their contribution to the institution. If we do that, they will give their heart and soul to the success of this institution. Then we all win. A $1,500 investment [for water] pays me a multitude of returns in what I get back in morale and camaraderie."

Gill, a former Salt Lake City prosecutor who took office in January after toppling Republican incumbent Lohra Miller in November's election, has proven during his first three months on the job that he's not afraid of one thing: change.

He eliminated fees the D.A.'s Office charged defense lawyers for discovery documents. He put into practice an early-case resolution program — started under Miller — that is resolving more than 30 percent of cases before they go to trial. He disbanded his predecessor's specialty prosecution teams and devised a system he maintains will lead to a better trained, more versatile staff.

Some of Gill's decisions have stirred controversy: He filed third-degree felony charges against former Cottonwood Heights police officer and former Salt Lake County sheriff candidate Beau Babka for allegedly using a city credit card to buy $48.17 worth of gasoline for two personal vehicles. Babka, in turn, was arrested hours later.

Gill's handling of that case prompted an opposition rally and criticism from the Fraternal Order of Police Utah State Lodge.

"What kind of message is the Salt Lake County District Attorney's Office sending to all law enforcement when they choose to make a spectacle of a police officer's despair?" Fraternal Order of Police officials wrote in a statement, noting that many suspects accused of first-time, nonviolent offenses are allowed to surrender on their own accord or are issued a summons to appear in court.

Other decisions have scored Gill political points: He reversed his predecessor's policy to charge for "discovery" documents such as police reports, photographs and videotapes that stand as evidence against defendants. The policy change ended a lawsuit by the Utah Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, claiming that the fees violated a defendant's rights.

Kent Hart, executive director of the association, called the change in leadership "refreshing."

"We cannot expect the prosecutor to adopt all of our requests or to change policies just because we ask," he says. "What we do expect is the county prosecutor to be open and available and willing to consider defense attorneys' concerns. Sim has done that."

Indeed, Gill has emphasized communication — with defense attorneys and others.

In his first 100 days, he has met with nearly every valley mayor, offering his cell phone number and a pledge to tailor prosecutions to community needs. His staffers meet with police chiefs and city attorneys as well, part of an initiative to give each city a direct "liaison" with the D.A.'s Office.

"If we don't talk to each other," Gill says, "we are not going to be able to trust each other."

That approach is bearing fruit in Draper, where Police Chief Arthur "Mac" Connole told Gill he would prefer not to send his officers to downtown Salt Lake City to screen felony cases. Gill said he would look into it. Within 10 minutes, before Gill had reached his first traffic light on his way out of town, the new D.A. had arranged by phone for the south-valley suburb to screen felonies in West Jordan instead.

For further evidence of what Gill hopes will become a more community-inclusive management style, consider:

Exhibit A: Stewart Ralphs, executive director of the Legal Aid Society of Salt Lake, doesn't object to Gill doing away with the D.A.'s dedicated domestic-violence team. In fact, he believes Gill may have come up with a "more successful" model. The proposal "did give me pause," Ralphs concedes. But when Gill, who was instrumental in creating Salt Lake City's family-justice center, explained the reorganization to the domestic-violence community, Ralphs became a believer. He now agrees that wrapping those cases into a wider violent-crime unit could improve prosecutions by giving more attorneys more exposure to those kinds of cases.

Exhibit B: A flier found in a stairwell hinting at dissatisfaction within the D.A.'s Office was distributed in an officewide email — by Gill. He says those conversations belong in the open. "Only a few people may have seen this," he wrote to employees, "but I wanted to let everyone see it because this was, after all, the desire of the person posting this. I want them to have their voice heard and not simply rush off in secrecy. The culture I want to change is this type of behavior."

Exhibit C: Although West Valley City Mayor Mike Winder endorsed Gill's opponent, he says he is "impressed" with the DA's performance. He mentions the DA's visit and says Gill told him "not to hesitate to call" on issues in which the District Attorney's Office can work in partnership with the city. "I appreciate people who understand that we duke it out on the campaign trail as Republicans and Democrats, but that, after the election, it is time to roll up our sleeves and work together to govern. Sim gets that."

That's not to say everyone is pleased with Gill. Blake Hamilton, an attorney representing several members of the now-disbanded domestic-violence team, told the Deseret News last month that Gill's decision to eliminate his clients' team — created to remedy an estimated 70 percent dismissal rate — "does a disservice to victims of domestic violence." Hamilton declined to comment for this story.

So what lies ahead? Gill plans to create a homicide unit, more aggressively prosecute gang violence as organized crime and hold a summit centered on child abuse.

Daniel Medwed, a criminal-justice professor at the University of Utah, gives Gill high marks for his first three months. He describes the disbanding of the domestic-violence team as "a more equitable first-come, first-served approach" to justice, praises the elimination of discovery fees as providing prosecutors and defendants "an even playing field" and defends Gill's handling of the Babka case as less about the amount of money involved and more about the alleged breach of public trust.

"He has a bright future," Medwed says. "He could be one of the nation's top prosecutors by the end of his term."

Also pleased: legal secretary Christine Hodge.

She no longer has to collect cash for water.

About Sim Gill

Age • 49

Family • Wife, Jamie Tabish; two children

Political party • Democrat

Education • Bachelor's degree in history and philosophy from the University of Utah, law degree from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Ore.

Hobbies • Golfing, reading philosophy, watching movies and cooking

Interesting fact • He and his daughter are Food Network junkies who love to cook together.