This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Provo • Lara Asplund considers the Provo LDS Tabernacle more than just bricks and mortar.

It's the heart of Provo, situated at the crossroads of the city's two main streets and a gathering place for Mormons and non-Mormons. And it needs to be rebuilt, regardless of the cost, she said.

"If you were in Rome and the Vatican were damaged, you wouldn't want to rip it down," Asplund said. "You would want to save it."

She's not alone. Even as firefighters were still battling the fire that consumed the building's interior, a Facebook group was forming to lobby The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to rebuild the tabernacle and even offered to raise money to do it.

Officially, the LDS Church is still weighing its options and has given no hints about which way it will go.

While some are anxious to see the tabernacle rebuilt, they agree the decision will involve multiple factors, including a price tag that will dramatically exceed the tabernacle's original $100,000 cost in 1883, and its value to the community.

"Rehabilitation of a building is always a complex process, both in the decision-making to do it and in its execution," said Kirk Huffaker, executive director of the Utah Heritage Foundation.

—

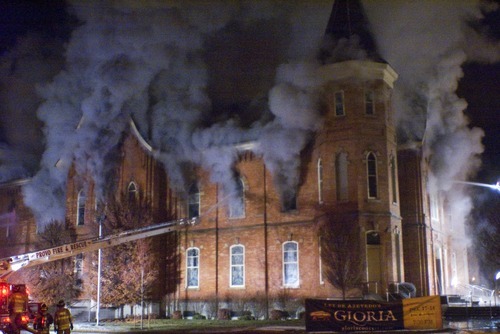

No decision • The 128-year-old building was destroyed by fire on Dec. 17. The blaze began when a technician hanging lights for a taping of Lex de Acevedo's "Gloria" left an energized 300-watt lamp sitting on a wooden speaker box in the tabernacle's attic. That misstep was compounded by an off-duty police officer who mistook the fire signal for a faulty burglar alarm and silenced the system.

By the time firefighters arrived at 2:44 a.m., the flames were burning through the ceiling and into the building's main hall.

Fire investigators estimated the damage — including musical instruments left in the building for the performance — at $15 million.

Immediately after the fire, the church hired Jacobsen Construction to shore up the walls with a massive scaffold of steel girders mounted on concrete footings. Jacobsen also provided cranes and crews to assist investigators in clearing debris, piling it in the park on the building's north side.

Jack Wixom, Jacobsen's vice president for corporate relations, would not comment on whether the church plans to reconstruct the tabernacle's interior. He said Jacobsen's task was to stabilize the building for further evaluation.

But the Jacobsen company has experience restoring historic buildings. It did seismic upgrades for the Utah Capitol, the City-County Building in Salt Lake City and the Salt Lake Tabernacle. It also transformed the former Brigham Young Academy building into the Provo City Library at Academy Square.

The project involved gutting the building's interior, and adding a steel frame to allow it to withstand an earthquake.

But such projects, Wixom said, usually cost more than building a modern structure from the ground up because of the work involved in meeting 21st century building codes. But he said when the decision is made to restore a building, money is usually not the deciding factor.

"In general, the decision was always made based on the cultural and civic value [of the building]," Wixom said.

L. Douglas Smoot is familiar with that balancing act. Smoot, an emeritus chemical engineering professor at Brigham Young University, led the effort to save Academy Square from the wrecking ball.

Unlike the Provo Tabernacle, public sentiment was initially against saving the building, which sat vacant for more than a decade and was becoming a graffiti-filled hulk. By 1995, the city was ready to raze the building.

But Smoot, whose great-grandfather was involved in building both the original Academy Square and the tabernacle, organized the Brigham Young Academy Foundation and made a deal with the city to save the building: The foundation would raise the $5.9 million difference between building a new city library and restoring the old BYU building.

Smoot's foundation raised $6.9 million, with $1 million going to a fund to help maintain the building, while Provo voters approved a $16.9 million bond to move the library to the former BYU campus.

"All this time since the building was completed [in 2001], I have never had one person … say it shouldn't be done," Smoot said.

—

Preserving history • Smoot said several factors favor the tabernacle reconstruction. First, its brick walls, in spite of the fire, are in better shape than Academy Square's were. He said the brick is fired clay, and appeared to suffer little, if any, heat damage during the fire.

Unlike Academy Square, the tabernacle was in active use at the time of the fire, and there appears to be public support for reconstruction.

Finally, Smoot said the tabernacle is owned by the LDS Church, which eases some of the financial questions. He said the church has the resources to commit to it.

Huffaker, with the Utah Heritage Foundation, said the LDS Church's track record on historical preservation has improved in recent years. He said the low point was the 1971 demolition of the Coalville Tabernacle in Summit County.

"There's an evolving ethic toward preserving these important places in local communities," Huffaker said. "You can see it in City Creek Center, where [the church] committed to the renovations of the old First Security Bank building."

The church also converted the Uintah Tabernacle into the Vernal Temple, preserving the historic building. It also saved the facade of Promised Valley Playhouse, building a new structure behind it to house offices.

Huffaker said the fire, in a sense, makes restoration work easier. Since the building is essentially an open box, it is easier to retrofit than a building that is still in use. He would like to see the church save the tabernacle.

Provo Mayor John R. Curtis is also hopeful the tabernacle will be saved. The day after the fire, he called the church's presiding First Presidency to ask what he could tell people of the church's plans for the building.

"They said, 'You can tell them two things. The first is, we understand how important this building is to the people of Provo. We get that. We know how much emotion is tied into it, and we feel the same way. We have those same feelings,'" Curtis recalled. "'The second thing is, you can tell them we will do the right thing.' "

But he predicted that if the church decides against rebuilding, there would be a groundswell of support for restoration, with people coming forward to pay for it.

One person pulling for the tabernacle to be saved is Kathryn Allen, executive director of Provo's Downtown Alliance. Allen said the tabernacle's programs, from concerts to the live Nativity during the holidays, brought people downtown and to its businesses.

"We will be sitting on pins and needles waiting to hear," Allen said.

dmeyers@sltrib.comtwitter.com/donaldwmeyers Provo Tabernacle: A brief history

Construction began on the Provo LDS Tabernacle in 1883. In 1885, a memorial service for Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was conducted in the building. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also conducted General Conference meetings in the tabernacle in 1886 and 1887. The building was officially completed in 1898.

The tabernacle originally had a center spire, in addition to its four corner towers. The spire was removed in 1917-18 because the roof could not support its weight, and the roof was shored up in 1949. The tabernacle underwent major renovation in the 1980s.

On Dec. 17, the building was destroyed by a fire started when a high-wattage lamp was left on a wooden speaker box in the attic.