This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Goshute • Tribal leaders here on the Utah-Nevada line worry that a proposal to pump groundwater from a series of valleys south of their reservation will drain their desert springs and what's left of their traditional life.

They are among hundreds of protesters who lodged formal challenges with Nevada officials by last month's deadline, although Las Vegas water officials say they have nothing to fear.

The Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation — about 560 American Indians, including 120 residents tucked behind the alpine crags of the Deep Creek Range 70 miles south of Wendover — rely on springwater for reservation taps and on regional streams for deer and elk hunting that draws sportsmen and their wallets here. They also need irrigation water for leased farmland.

But the threat of lost water transcends life, death and money, tribal elders say. In this dry landscape, water carries a soul.

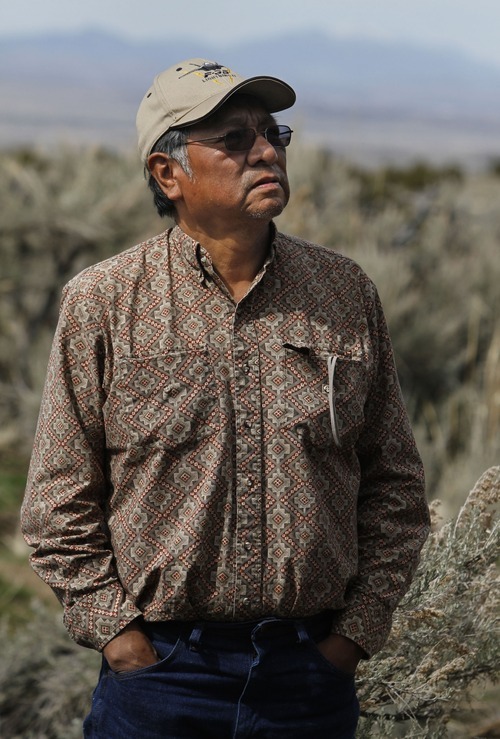

"We know our ancestors for a long time left their spirits here," former tribal chairman Rupert Steele said while standing above a spring that gushes from a rocky outcrop on the reservation's Nevada side, coursing past chokecherries and into a pond that the Goshutes and government biologists are using to help restore rare Bonneville cutthroat trout.

The Goshutes conduct ceremonies at the spring, he said, and some come to sip from it and "talk to the water" when ill.

"If this dries up," Steele warned, "that goes away. We have no place to practice our spiritual ways."

The Goshutes are one of 200 groups and individuals who have protested some or all of the Southern Nevada Water Authority's applications for wells with rights to draw 120,000 acre-feet of groundwater annually from Spring Valley and nearby valleys (Cave, Dry Lake and Delamar) southwest of here. An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons, or enough to supply a typical household for a year in this climate. An additional 250 people have signed on to the nonprofit Great Basin Water Network's protests.

Protesters include The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which owns a ranch that could be affected, and Salt Lake County, which fears dust storms if desert vegetation shrivels.

Formal protests to the Nevada state water engineer give the filers standing to make their case when Nevada considers the applications this fall. The engineer will rule later on applications and protests for Snake Valley, straddling the state line west of Delta.

It's scientifically challenging to predict how pumping from one valley affects the next, and Las Vegas water officials say their studies indicate the Goshutes likely won't see any change in groundwater. But the Goshutes, with help from Round River Conservation Studies, a Salt Lake City nonprofit aiding indigenous peoples, contracted a hydrologist who says it could see an impact — especially at fast-flowing springs such as the one Steele frets over.

A government study of wells and mathematical models, conducted for the Interior Department, suggested all planned regional pumping, including for the Las Vegas pipe, could drop Deep Creek Valley's water table a couple of feet — far less than the 100 to 200 feet it predicted for Snake and Spring valleys.

"There will be extensive destruction of [plants] in Snake and Spring valleys, and also impact on springs," said Tim Durbin, a hydrologist with California-based West Yost Associates, hired to conduct the Interior Department study. There is potential to deplete springs at the foot of Great Basin National Park, he said. The National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which operates several marshland refuges in the region, are among the protesters.

The plan would affect traditional Goshute hunting and gathering grounds, said Durbin, who previously worked for the U.S. Geological Survey in Nevada.

The Great Basin Water Network was pleased with the number of protests from within the rural valleys directly affected, said Steve Erickson, the group's Utah coordinator, who noted that most protests came from within Nevada.

"Public opposition is still out there in those valleys," he said, "and we believe that's only going to grow."

Utah did not protest this round of applications, though it has done so for others in Snake Valley. Department of Natural Resources Director Mike Styler said Snake is the only valley in question to overlap the two states, and even with interconnected plumbing he thought it best to respect Nevada's jurisdiction elsewhere.

"Spring Valley is 30 miles inside the border," Styler said, "and we thought that would be a little overreach."

The Utah-based LDS Church protested some well applications near its Cleveland Ranch. Salt Lake County protested because of air-quality concerns, while Juab and Millard counties, both farm-dependent and taking in parts of Snake Valley that could be affected by Spring Valley pumping, also filed against the plan. So did a Nevada county, White Pine, effectively setting up a rural-urban battle within the Silver State.

It shouldn't be that way, Southern Nevada Water Authority spokesman J.C. Davis said. If allowed to build and use its pipeline, he said, the authority maintains pumping would undergo constant monitoring to ensure it doesn't deplete Spring Valley groundwater, let alone adjacent valleys.

What's more, he said, Nevada law makes clear that it's legal to transfer water from one basin to another. And economic development in Las Vegas helps pay for projects and services statewide.

Las Vegas needs the water as an insurance policy against drought in its main source, the Colorado River Basin that feeds Lake Mead, Davis said. The lake level is below 1,100 feet elevation, and at times last year was down to 1,075, compared with elevations above 1,200 feet in years past. Once it drops below 1,050 feet — something several dry years could cause — states with claims to the Colorado would have to hash out restrictions. At 1,000 feet, the city's water intakes would be dry.

Las Vegas last year used 32 billion gallons less than in 2002, Davis said, despite growing by 400,000 people since then. The water authority isn't seeking water for growth, he asserted, but for security.

"Our job," he said, "is to make sure when you turn on the faucet, water comes out."

The water authority says no evidence shows Goshute residents would suffer — even from Snake Valley pumping, not to mention Spring Valley farther south.

The claim is of little comfort to the Goshutes, who say the replenishing snowfall in the mountains surrounding their lands has declined during the past generation.

"We will defend our right to continue living in harmony without harm to our precious, most valued resources," Tribal Councilwoman Madeline Greymountain said in a written statement after filing the protests, "and we welcome all the help we can get from caring people and communities willing to support our efforts."

bloomis@sltrib.comTwitter: @brandonloomis