This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

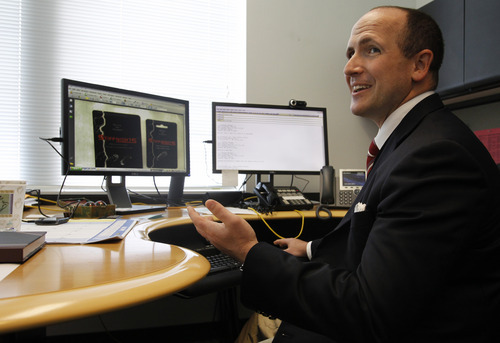

Washington • He was the public face of the nation's largest dietary supplement trade group and now he's the federal government's point man on regulating the supplement industry.

Daniel Fabricant's jump from industry insider to industry regulator is far from unusual in Washington, where former Wall Street executives occupy top spots in the Treasury and defense contractors work inside the Pentagon.

But it's unprecedented for the Food and Drug Administration to embrace a champion of supplements, especially after decades of bitter feuds between the agency and the sector, which is a major force in Utah's economy. For veterans of those vitamin wars, this moment symbolizes a historic turning point.

"For the first time, FDA's director of Dietary Supplement Programs will be someone who thinks there is real value in the category — that these products can provide a substantial benefit to human health," said Marc Ullman, a New York-based attorney who represents supplement companies.

While industry leaders celebrate Fabricant's hiring, others criticize the agency for getting too cozy with those it oversees.

"It's outrageous. It shouldn't happen," said Sidney Wolfe, the director of the health research group at the watchdog organization Public Citizen. Wolfe, a longtime critic of the FDA, said if the agency hired someone from a pharmaceutical trade group to oversee drug regulation "there would be a huge uproar and there should be here."

—

Credibility at stake • FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg declined to explain her reasoning, but Fabricant defended himself, saying the agency "wants people who understand the issues."

"Knowing the industry certainly is a unique skill," said Fabricant, who resigned as vice president and spokesman of the Natural Products Association in February after accepting the job at FDA.

He said his friends in the industry are "sorely mistaken" if they believe he won't aggressively go after companies that skirt the law and he noted his credibility is at stake.

"We have a responsibility here to develop a robust safety program for dietary supplements," he said, emphasizing that he doesn't "speak for the industry."

But he does speak to the industry, and often. Fabricant has encouraged more conversations between company executives and his staff in an attempt to streamline reviews of new dietary ingredients.

The agency has held private meetings with supplement makers to discuss the findings of government inspections after new manufacturing requirements were implemented for all companies in 2010.

And late last year, before Fabricant's hiring, the agency announced its first joint program with the four major supplement trade groups focused on eliminating supplements spiked with pharmaceuticals or illegal drugs, particularly in the areas of weight loss, sexual enhancement and weight lifting.

Peter Barton Hutt worked for the FDA as its general counsel in the 1970s and has represented the Council for Responsible Nutrition, another major supplement trade group, for more than two decades. He says the shift in relationship from outright hostility to one built on trust is something he couldn't have envisioned a decade ago.

"There has never been a better working relationship between the industry and the FDA," he said.

—

Vitamin wars • A SWAT team equipped with assault rifles and night vision goggles raid a Los Angeles mansion, only to find actor Mel Gibson in his kitchen holding a bottle of Vitamin C.

They put him in handcuffs.

This iconic TV ad from 1993 (using actors playing officers) epitomizes how the supplement industry viewed FDA, as an agency obsessed with cracking down on its products. And it was just one part of a broad media campaign responding to a controversial decision by then-FDA Commissioner David Kessler.

He wanted companies to prove that scientists were in general agreement about the benefits of a product before it started advertising those benefits, essentially adopting the same standard set for foods. Only a small handful of supplements would likely ever reach such a standard.

"That regulation set off a firestorm," Kessler said. "One of my colleagues described it as if there was this sleeping dog that we just ran by and kicked."

Hutt called Kessler's decision "a declaration of war" equal to past FDA campaigns that would have limited the potency of vitamins.

"In effect, he was saying 'I want to put you people out of business,'" he said.

The industry seized on that idea, telling customers the FDA wanted to take its supplements away or require them to get a prescription. Some health food stores even gave discounts to customers who wrote letters to Congress.

As a result, tens of thousands and, by some accounts, hundreds of thousands of letters poured into congressional offices demanding that Congress block the FDA's proposed legislation and protect their access to supplements. Kessler said he never attempted to restrict access to supplements, though his skepticism about their benefits was hard to miss.

"The industry knew that billions of dollars depended on this and it was going to defend those revenues," Kessler said recently. "That was what this was all about."

—

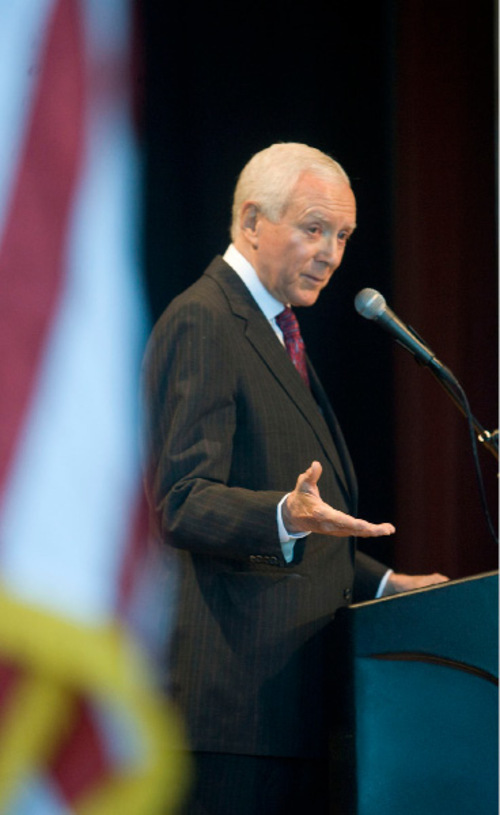

Getting personal • Kessler's biggest legislative opponent turned out to be his former boss — Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah. Kessler worked for Hatch in the 1980s and the senator didn't like that one of his own was now calling for tighter controls on products he holds dear.

"I didn't blame David for wanting to overregulate them. That was his nature," Hatch said. "And he was very well intentioned, but very risk adverse, so much so that his views would have killed the industry had he been successful."

Hatch has deep personal and political ties to the supplement community. He once owned stock in a supplement company. Many of his former staffers and even his son have lobbied for the industry. And in the past two years alone, he has received $100,000 in campaign contributions from people connected to dietary supplements.

At the time of Kessler's proposed rule, Hatch and the industry argued it was financially unfeasible to require supplement companies to conduct detailed scientific tests. Their products come from nature and by definition are not patentable, so the investment would be almost impossible to recoup. Also, they said, the products, by and large, don't hurt people.

So Hatch championed a bill written with the blessing of supplement manufacturers, to bar companies from saying a product cured a disease, but allow them to say it helped with a certain function of the body, say digestion, or part of the body, such as bones or the heart. It also blocked the agency from recalling products unless it could prove the supplement had a reasonable risk of harming someone, putting the onus on the agency instead of the manufacturer.

Hatch said his bill, known as the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), achieved a careful balance — protecting the public while ensuring that consumers could buy the products they want.

The FDA saw it differently. Kessler's chief deputy said Hatch's legislation would "eliminate any meaningful scientific standards for the validity of claims and any meaningful FDA role in evaluating the safety of those products."

DSHEA became law in 1994, passing after congressional Democrats struck a deal just a few weeks before Election Day.

"As I was told, David Kessler nearly had a stroke. He couldn't believe it," said Loren Israelsen, the executive director of the Utah-based United Natural Products Alliance and a major supporter of Hatch. "He became such a personal opponent. It was a humiliating defeat."

While people inside and outside FDA say the debate became emotional, Kessler denied that he had any hard feelings.

"It was never personal. It was about what the right public policy standards should be," he said.

Since the passage of DSHEA, the supplement industry has grown from $4 billion in annual sales to $27 billion and the number of Americans using the products has doubled. A recent government survey found that half of all Americans, more than 150 million, take at least one supplement.

Kessler has watched the law in action and noted that the overwhelming majority of products are safe, but he remains a critic, believing DSHEA allows companies to deceive customers, providing little or no proof that a supplement makes them healthier.

—

Healing bruises • As the industry reveled in its success, officials at the FDA licked their wounds. They took slow steps to implement DSHEA, creating a small office of dietary supplements, and deciding when a health claim was acceptable and when it was not.

In essence, major portions of the bill remained dormant for more than a decade, in part because Congress passed the law without providing any funding. Animosity remained and there was little to no interaction between the regulators and the industry they regulated.

"There was still a lot of bruises and a lot of healing that needed to be done. It was the end of the war," Israelsen said.

The agency took six years to finalize a rule on health claims and 16 years to fully implement manufacturing standards. It took a decade for the agency to ban the use of ephedra, a product believed to have seriously injured and even killed people.

One section of the law that remains in flux is a review of new dietary ingredients, though the agency plans to boost its efforts later this year.

The FDA and its congressional allies have stopped arguing that companies should be required to prove their products work as advertised and have instead focused almost exclusively on whether the products have any potential safety concerns.

In turn, the industry trade groups have advocated for more FDA funding and aggressive action against rogue companies.

"The consensus is that good regulation is helpful to the industry as a whole. It helps with consumer confidence. It helps the industry grow," said John Gay, executive director of the Natural Products Association. "It is not that we are buddy, buddy, but it is how much has improved since we were mortal enemies with the FDA."

—

Enemies no more • Gay said the hiring of Fabricant, his former employee, is "a landmark in the relationship and a sign that things are only going to get better between the agency and the legitimate industry."

Fabricant, who has a chemistry background, is now in charge of monitoring the marketplace for unsafe products and illegal medical claims. His team also tracks injury reports, reviews new ingredients for safety and assists in the inspection of supplement manufacturing plants.

He is the fifth full-time director of the Division of Dietary Supplement Programs, replacing Bill Frankos, who left FDA in 2010 for a job with Herbalife, a large supplement company based in California. Frankos is the first high-ranking FDA official who left to work for a supplement company.

Fabricant says the industry and the agency have the same end goal of ensuring safe, reliable supplements. He points to a beefed-up safety program, including a mandatory report when customers say a supplement caused a medical condition. When he compares what he did as a trade association spokesman and what he does now, he says, "I don't think it is a big shift."

Ethics rules limit Fabricant's ability to get involved in issues in which his former employer has been active until February, but there's one focus he wants to carry forward: a renewed effort to criminally prosecute companies that illegally spike supplements.

Wolfe, the FDA critic, thinks that's exactly what should happen, though he doubts "an industry front person" is likely to lead the charge.

But for Kessler, who is now an academic in San Francisco, spiking is a side issue and the real question is whether the industry and the agency can "look at the public with a straight face and say that they can ensure the safety, integrity and claims of its products," he said. "That is key."

Supplement oversight

The way the FDA regulates dietary supplements is far different than the way it oversees food or drugs.

Medical claims • Under the law, a supplement company can say a product is good for heart health but can't say it lowers blood pressure. Those more direct claims are reserved for drugs, which are proven through blind trials to treat or cure a disease, while supplements, which are not as rigorously studied, are only allowed what the FDA calls structure or function claims.

Adverse events • Companies, doctors and consumers give the FDA reports anytime someone believes a supplement caused them harm. These adverse event reports are then examined for trends.

Good manufacturing practices • The FDA has created rules for the production of supplements in an attempt to ensure that only pure ingredients are used and that what is on the label is actually in the bottle. Starting in June 2010, the agency could conduct a spot inspection on any manufacturing plant.

New dietary ingredients • Any ingredient on the market before the passage of the 1994 supplement law is legally considered safe. Any company using a new ingredient is supposed to submit safety data to the FDA, which has 75 days to raise an issue. These reviews have been sporadic and companies claim the regulations are not clear. FDA plans to issue a clarification to the rules by the end of June.