This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Huge mountain snowpacks, along with continued wet and cold weather, are dredging up memories of the spring of '83 and the flooding that transformed Salt Lake City's State Street into a river.

But the flooding 28 years ago didn't just happen in Salt Lake County. Then-Gov. Scott M. Matheson declared 11 counties disaster areas when high waters and mud flows undercut roads, flooded homes, washed out utilities and swamped farmland.

There are some startling similarities between then and now.

Record rains in September 1982 saturated soils and set the stage for massive spring flooding from the Weber River in the north to the Sevier River in central Utah. Snow continued to pile up in mountain areas until late May.

As in 1982, the fall of 2010 was exceedingly wet. But the snowpack this spring is significantly deeper than it was in May of 1983, according to the National Weather Service.

"You should have 90 days of the water from snowpack flowing normally out of the mountains," said LeRoy Hooten Jr., the public works director for Salt Lake City in 1983 who is now retired and still lives here. "But when you go quickly from winter to almost summer weather, it goes into one large flush."

National Weather Service computer models based on data from the last 30 years indicate there is now about a 25 percent probability that City and Emigration creeks could surpass flood stage. But both drainage systems have been much improved since 1983, according to Jeff Niermeyer, Salt Lake City public utilities director, making significant flooding less likely. And a new reservoir, Little Dell, has since been built to catch excess runoff.

Back in 1983, water officials began to get an inkling by March that trouble lay ahead as cold, wet weather continued. They began lowering reservoirs — as water managers are doing now — to keep stream flows below flood level, Hooten said. Mountain Dell Reservoir was in danger of spilling over the dam.

"The first problem was that it could threaten the integrity of the dam and flood a major highway system," he said of Interstate 80 in Parleys Canyon.

"The harbinger was the major event in Spanish Fork Canyon," recalled Hooten. A massive April 16 mud slide filled the canyon, blocked U.S. Highway 6 and dammed the Spanish Fork River, which backed up and drowned the small town of Thistle.

When temperatures zoomed into the upper 80s in May, massive mudslides hit Bountiful, Farmington and Fairview.

Giggi Madsen remembers the night of May 30, 1983, when a wall of mud washed down Stone Creek above Bountiful and slammed into her house at 910 E. 350 North.

"I was as scared as I ever want to be," she said recently. "We heard this sound like an earthquake, and my husband yelled, 'Get out.' "

The Madsens had to rebuild their house. Statewide, damage and losses for the two weeks of flooding were well over $100 million in 1983 dollars.

Grant Mabey, chairman of the Salt Lake City Council in 1983, had witnessed the flooding of Salt Lake City in 1952 and remembered that runoff was channeled down 1300 South to avoid widespread flooding then. In the spring of '83, he became fearful that 1952 was about to repeat itself.

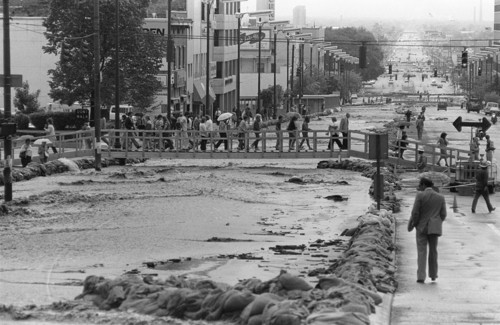

"I called Mayor Ted Wilson and told him, 'I think we're going to have a flood like 1952,' " Mabey remembered last week. "We got a quarter of a million sandbags and ordered more."

Mabey and others in the Salt Lake City stakes of the LDS Church began to organize a volunteer sandbag force. "If we did have a flood, we'd be ready to go," he said.

On May 26, Salt Lake City and Salt Lake County officials declared an emergency and diverted rising runoff waters from Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys creeks down the roadway on 1300 South from a pumping station at 700 East. The street became a waterway from West Temple to the Jordan River.

With water flowing down 1300 South and disaster averted, people were feeling pretty good, former mayor Wilson recalled recently.

"In the spring [of '83], we had a weather pattern like this year," said Wilson, who is now an advisor on environmental matters to Utah Gov. Gary Herbert. "By May, we were buying sandbags and getting ready. But we still didn't think we'd get a cataclysm."

Just when there seemed to be relief, Al Haines, Wilson's chief administrative officer, said hydrologists came to him with serious concerns about City Creek Canyon.

"Frankly, we hadn't been paying much attention to City Creek," he said recently in a telephone interview from Houston, where he now lives.

"The oh-my-gosh moment came Saturday morning [May 28]," Haines said. "Our hydrologists forecast a runoff after Memorial Day [May 30] that would exceed the capacity of the [City Creek drainage] system."

That drainage system, which runs under North Temple, had been holding until then, Wilson recalled.

"But because City Creek was churning up the canyon, the pipeline on North Temple would get clogged with debris," he said.

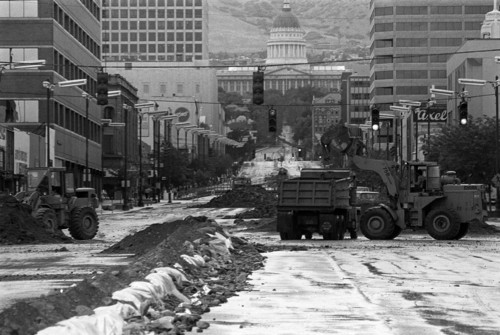

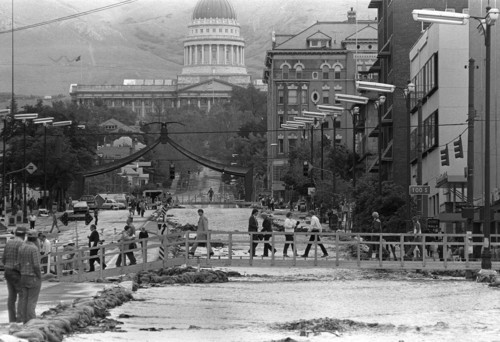

City engineers told Haines it was possible to channel the creek down State Street to the storm drain system at 400 South.

On May 29, Wilson called LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball and other church leaders to request volunteers. By 7:30 that evening, sandbag dikes from Memory Grove to 400 South were completed just as City Creek turned into a brown, raging monster.

Then the 400 South storm drain system, too, became overwhelmed. The next day, volunteers built sandbag dikes farther down State Street to the 900 South drainage system.

Once the second disaster had been averted, Wilson and his administration faced another big problem: Commuter traffic on 600 South and 500 South heading to and from Interstate 80 was blocked by the State Street river. It threw downtown into utter confusion, recalled Alma Allred, who managed the parking facility beneath the old ZCMI mall. His initial concern, he recalled last week, was that the parking structure would be flooded. After the dikes on State Street were built, his worry changed: The new waterway was keeping automobiles from getting to the parking area.

After some hand-wringing, Wilson and Haines determined to bridge the river on both the 500 South and 600 South thoroughfares. By Monday, June 6, city crews had built one-lane bridges of earth and steel culverts and downtown was open for business.

"It saved the city," Wilson said. "But the kayakers called to complain they couldn't get under the bridges."

Haines, too, recalled criticism for the bold move. "They said, 'You're going to spend $25,000 on two bridges and tear them down in two weeks?' "

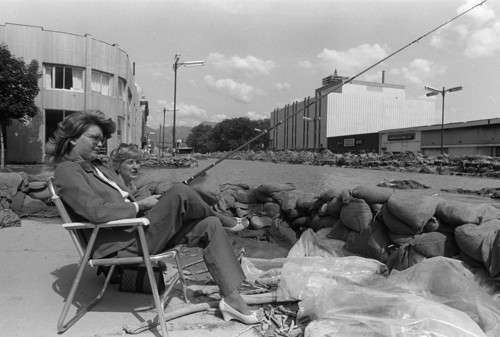

State Street had become something of a tourist attraction with footbridges over the temporary river. One Salt Lake Tribune photo from the first week in June shows painters with easels capturing the scene.

But it wasn't necessarily good for business as shoppers stayed away, leading the Salt Lake Area Chamber of Commerce to launch a campaign to lure them back.

Nonetheless, downtown businesses and their employees attempted to take it all in stride. Allred was photographed holding a 13-inch rainbow trout on May 2 that had come out of the State Street river. He's now director of commuter services at the University of Utah, and recalled how the waterway changed downtown overnight into something of a noisy Venice.

"It was just astounding," he said.

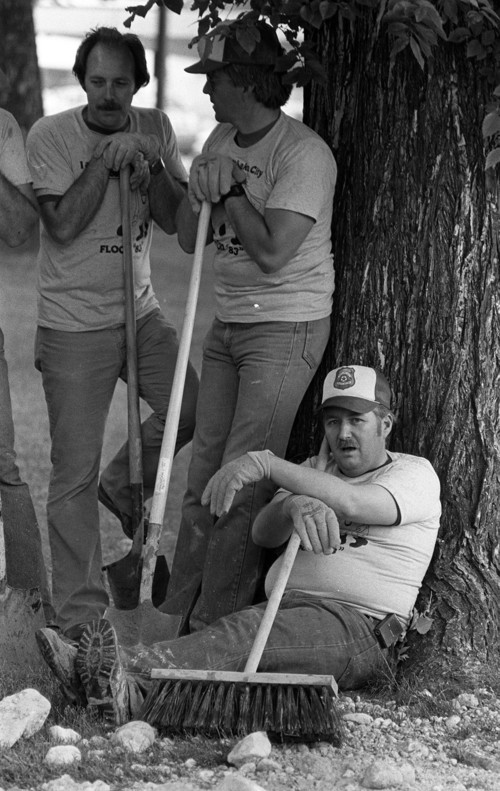

It also was short-lived. By June 11, City Creek had receded and was again channeled under North Temple. The State Street river dried up. A massive cleanup effort got downtown back to normal within a week.

The State Street river was bad for business, Allred recalled. "But I think back fondly on it now."

A timeline of 1983 flooding

Sept. 26, 1982 • Giant storm floods houses and highways in Salt Lake Valley. It was the wettest September in Utah history with 4.35 inches of rain.

April 17, 1983 • Mud buries U.S. Highway 6 in Spanish Fork Canyon; Thistle evacuated.

May 19, 1983 • Massive snow slide closes Alta for a week.

May 26, 1983 • Salt Lake County declares flood emergency and closes 1300 South from West Temple to the Jordan River to facilitate high flows from Emigration, Parleys and Red Butte creeks.

May 27, 1983 • Mud slides force evacuation of the Pinecrest area of Emigration Canyon.

May 28, 1983 • Flood waters surge down City Creek Canyon.

May 29, 1983 • Temperatures hit 90 in northern Utah. State Street sandbagged to divert floodwaters.

May 30, 1983 • Massive mud slides descend on Farmington, Davis County and Fairview, Sanpete County.

May 31, 1983 • Water and mud from Stone, Barton and Mill creeks flood Bountiful neighborhoods.

June 2, 1983 • Eleven Utah counties declared disaster areas by Gov. Scott M. Matheson: Salt Lake, Davis Weber, Juab, MIllard, Sevier, Carbon, Sanpete, Utah, Emery, Beaver, Morgan and Wasatch.