This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

An enforcement-only immigration law set to take effect next week is unconstitutional and will foster racial profiling in Utah, according to a lawsuit filed Tuesday in federal court by several civil-rights groups.

The lawsuit targets HB497, a bill sponsored by state Rep. Stephen Sandstrom, R-Orem, originally modeled after Arizona's SB1070 enforcement-only law. The Arizona law, signed more than a year ago, ignited a firestorm of controversy and had major sections of it thrown out after it was the target of a lawsuit in federal court.

The Utah version, however, was tempered during the legislative session, and Sandstrom adjusted several parts of it to avoid the lawsuits that SB1070 drew.

But the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Immigration Law Center and several local groups and individuals disagreed that HB497 is a diluted version and, in their lawsuit, are asking the federal court to issue an injunction to stop the law before it takes effect May 10.

Karen McCreary, executive director of the ACLU of Utah, said there isn't a question that it's a mirror of Arizona's law.

"This law has been widely misrepresented as a kinder, gentler version of Arizona's discrimination law," McCreary said. "But the truth is, this ill-conceived law is just as harsh, turning Utah into a police state where everyone is required to carry their papers to prove they are lawfully present."

The lawsuit says the state law violates several tenets of the U.S. Constitution, including the federal government's job of overseeing immigration law, as well as the Fourth Amendment's prohibition of unreasonable search and seizure.

It also argues that the law will encourage racial profiling and puts an undue burden on local police in attempting to determine the legal status of anyone stopped, detained or arrested.

But state Attorney General Mark Shurtleff said it's clear that Utah's law isn't Arizona's law.

"They're speaking on Arizona law in the lawsuit," Shurtleff said. "We walked, step by step, HB497 side by side with SB1070 and side by side with Judge [Susan] Bolton's rulings, and the parts she found in violation of federal law — each one of those — we looked at removing."

"I'm hoping Governor Herbert and Attorney General Shurtleff will defend my bill with as much zeal as they are defending HB116 [the guest worker law]," Sandstrom said Tuesday. "If the AG fights it properly and the state doesn't back down, I think we can beat the ACLU on this."

Sandstrom's changes from the bill's original version included making it optional for law enforcement officials to check legal status when a person is suspected of committing a class B or C misdemeanor and removing a mandate that officers check status upon "reasonable suspicion" that the person is in the country illegally. Shurtleff said the plaintiffs are misreading the law by attempting to equate it to Arizona's stricter immigration-enforcement provisions.

Juan Manuel Ruiz, president of the Latin American Chamber of Commerce, joined the lawsuit and said that the way the bill is structured, it creates an uneven approach to applying the law.

"We have received phones calls from specific areas of the state, where we know this law will be more harsh with their citizens and people of color versus other areas of the state," he said. "Unfortunately, the areas that have received the most concern are Utah County and Ogden."

Gov. Gary Herbert, who signed the bill into law in March, along with three other immigration bills, is named as a defendant in the lawsuit, along with Shurtleff. It is the first of the four immigration bills he signed to face a court challenge. A guest-worker bill, HB116, has been targeted as unconstitutional as well by opponents and is currently the subject of a repeal movement.

Herbert criticized the lawsuit and said the plaintiffs should be "proposing and advocating realistic immigration reform rather than pursuing litigation against those who are trying to deal with our current problems."

The governor called the so-called Utah Solution "a common-sense solution to the practical realities created by the federal government's inaction."

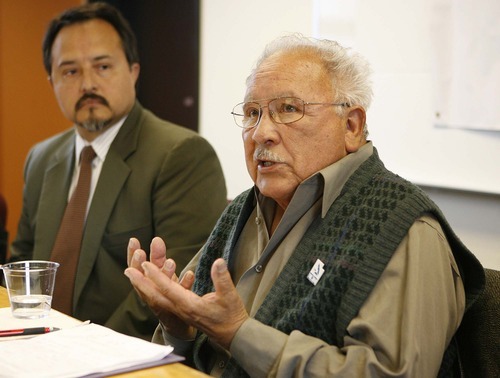

Archie Archuleta, a plaintiff and member of the Utah Coalition of La Raza, said the bill has created a chilling effect in the Latino community.

"You could not script a better fear-producing scenario than this," he said. "And because of this … people have expressed these fears: 'What will happen to us?' And the past pictures paint some pretty ugly pictures."

He talked about images of people "manacled" and being hauled away on buses and how families were divided. Those involved with the lawsuit said it also violates the spirit of the Utah Compact, a document signed by politicians, business leaders and faith groups — including a key endorsement from the LDS Church — that sought a compassionate approach to the issue of illegal immigration.

Three plaintiffs in the lawsuit are highlighted to make that point.

David Morales — identified as a John Doe in one of the cases — is a 19-year-old brought to Utah when he was 9. He wanted to be a Christian pastor and was accepted into an academy in Louisiana, but the bus he was traveling on was stopped at a U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint. He was arrested.

According to the lawsuit, he spent 17 days in immigration detention and is required to report to a program officer twice a month while his case works its way through the system. In the lawsuit, he said he worries that, with HB497, if he is stopped for any reason and "detained for even a brief period of time, it could violate the terms of his release program" that require him to check in with the officer.

Another plaintiff in the lawsuit, Eliana Larios, is a U.S. citizen who travels between Utah and Washington state to visit family and fears her Washington driver's license will "subject her to police interrogation and detention because of her Latina appearance" and that Washington doesn't verify immigration status as a prerequisite to obtain a driver's license.

Lee Davidson contributed to this report

dmontero@sltrib.com Twitter: @davemontero —

Online: Readthe lawsuit

O bit.ly/jG3fK0