This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

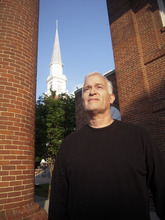

Columbia, S.C. • Sunday service at the First Baptist Church in Columbia has just ended, and Rex Rish is tying up a few loose ends with the video broadcast of this week's sermon.

Rish has been coming to this historic church for a quarter-century and volunteers on the technical side to help with the broadcast that hits five stations throughout South Carolina. He considers himself a devout Baptist.

Under the conventional wisdom about Southern Baptists — a group that has in the past condemned Mormonism as a cult and its followers as non-Christian — Rish should quickly dismiss the idea of voting for a Mormon for president. Except that he doesn't.

"If they can fix this country, I'd vote for someone with purple polka dots," he says.

Since the founding of their faith in 1830, Latter-day Saints have faced critics who say the religion doesn't fit within the Christian fold. And nowhere in the United States is that concern as palpable as deep in the Bible Belt of the South, where Baptist and Protestant faiths are woven into the fabric of the community.

As Mormons Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman Jr. consider presidential bids, they face questions of whether their faith might pose a hurdle in this part of the country.

The good news for the two LDS hopefuls is that residents say their attitudes are shifting — albeit slowly — in the political arena.

Rish, for one, acknowledges he doesn't believe members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are "doctrinally correct." But he says his decision in supporting candidates is more about what they stand for than what church they pray in.

"I'd like a candidate to be a mirror image of me, but that's not going to happen," he says. "So the best I can do is vote for the one that will run the country the best."

Historic and changing • On Dec. 17, 1860, South Carolina residents gathered at the First Baptist Church in Columbia to draft secession papers that led to the Civil War.

Five years later, Union General William Sherman ordered the brick chapel burned to the ground — though, as legend goes, it was only partially damaged after a church custodian directed Sherman's Army to the Methodist church down the street.

On a recent Sunday, the Rev. Wendell Estep quips that he's letting parishioners go early so they can beat the Methodists to wherever they're going.

The banter is all in fun, of course. The two churches are so close together, Methodists and Baptists park their cars next to each other and head to their respective chapels.

The local Mormon ward, about 10 blocks away, is a little too far to share parking, though churchgoers say they wouldn't mind. Nor, it seems, would many balk at supporting a Mormon for political office.

"I don't think that should matter," says Ben Gause, who has been coming to this church since 1982. "There are a lot of things that have changed in 20 years."

"I think we're getting more broad-minded," says his wife, Olga.

If perceptions have changed toward Mormons, part of the explanation may lie in the expansion of the Salt Lake City-based church.

In 1980, the church counted 11,881 members in South Carolina. In the '90s, it jumped to 23,000. The church dedicated a temple in Columbia in 1999 and now says there are 36,947 members in the state.

That still makes Mormons a tiny minority in the state of more than 4.5 million and compares with the some 45 percent of South Carolinians who align themselves with an evangelical Protestant tradition, according to a survey by Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

Catholics are also a minority — 8 percent, according to the same poll — in South Carolina, but in 2010, voters elected Mick Mulvaney, a Catholic, to Congress.

"Folks don't care about what particularly faith you are from," Mulvaney says. "They want to know about your values and whether or not you have the nerve to stand up for your values when you vote."

Estep, the revered pastor of First Baptist Church in Columbia for 25 years, says President John F. Kennedy's ability to overcome concerns about his Catholic faith in 1960 was a turning point in how people view religion when it comes to elected office.

Kennedy's win may have started a long process of breaking down walls between faiths; his famous line that people aren't voting for a pastor-in-chief helped.

"Of course, South Carolinians will be interested in a person's relationship to God," Estep says during a recent visit to his office. "I think that's a part of our heritage. They're also going to be interested in the economy, interested in jobs, they're going to be interested in the Constitution, interested in those basic issues."

Estep believes Mormonism is a cult, and he has concerns with some of the faith's doctrinal beliefs, but that won't preclude him from voting for a Mormon should that person share his concerns about domestic issues and above all, have faith in the "God of the Bible."

"It would be an issue for me, but it is not the exclusive issue for me," the reverend says. "I am interested in where people stand on policies."

Running as a Mormon: Rep. Alan Clemmons is a real estate attorney in Myrtle Beach and the only Mormon in the 170-member South Carolina Legislature.

When the Mormon caucus convenes, "we always have 100 percent attendance," he jokes.

A fourth-generation Mormon, Clemmons first ran for office in 2000, hoping for a state Senate seat, and says he saw rumblings of an anti-Mormon campaign against him — nothing overt, he says, more of the over-the-back-fence whisperings about his faith.

He lost that race against an entrenched Democrat but came back two years later to win a seat in the state House, where he remains.

"South Carolina has been described as the buckle of the Bible Belt, and I'm proud to be part of the Bible Belt mentality," Clemmons says. "Faith matters to South Carolinians. … Where you fall in a particular faith doesn't matter as much these days as it does that you are a person of faith."

Last year, the state voted in Republican Nikki Haley, a move remarkable only because of Haley's background. The first-generation American was raised in the Sikh faith by her parents, who immigrated from India. She married a Methodist six years ago and now considers herself a Christian.

The state also elected its first black Republican to Congress, Tim Scott.

"That speaks volumes to the notion of bigotry in the South and where the South has come over the years," Clemmons says. "I believe that the old Southern perceptions of religious and racial bigotry are just that — they are old. That's in the past. This is a new day."

During Romney's last bid, anti-Mormon literature occasionally found its way into voters' mailboxes and inboxes. One card, purporting to come from the Boston LDS Temple, quoted the late LDS Apostle Orson Pratt about plural marriage.

Another eight-page document zipped through email forwards: "Can Mitt Romney Serve Two Masters? The Mormon Church vs. the United States of America."

Richard Land, the president of the 16.3 million-member convention's ethics and moral arm, The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, says Baptists consider Mormonism "another religion. It's not Christianity."

That said, Land notes that if two candidates were equal in all other things but one was a Mormon and one an evangelical Protestant, Baptists would go for the evangelical. But if a Mormon aligns more with their values, he or she could find support.

Proof of that can be found on Sundays around the state.

Rish, of First Baptist Church, recalls volunteering for Ronald Reagan's first campaign in 1980 and a woman telling him she'd never cast a vote for Reagan because he had been divorced.

"Things have changed," Rish says. "Everyone has something I'll disagree with. But if you can run the country well, I'll vote for you."

facebook.com/politicalcornflakes

Twitter: @thomaswburr —

South Carolina presidential primary

The Palmetto State prides itself on the fact that the winner of its Republican presidential primary has gone on to win the GOP nomination in every election since 1980. Its place as one of the first four contests in the nation — and the first in the South — helps secure its importance in the process.