This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

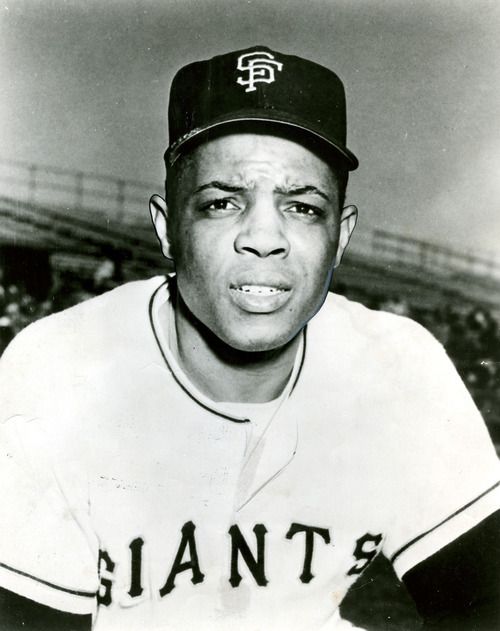

Certainly, one wouldn't guess from his major league debut on May 25, 1951 — 60 years ago Wednesday — that Willie Mays would become baseball's greatest all-around player as well as the first black athlete to truly cross racial lines and become an American superstar. Sixty years ago, the 20-year-old went hitless in five at-bats in Philadelphia.

In fact, Mays didn't hit safely in his first 12 times to the plate. He wondered if he belonged.

Then his first hit announced with terrifying consequences what opposing pitchers would have to deal with for the next 22 years.

Mays, only 5-foot-10 and 180 pounds, muscled a pitch from Braves future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn over the left-field roof and out of the legendary Polo Grounds, next to Coogan's Bluff.

Years later, upon his own induction to the Hall of Fame, Mays was asked who was the best player he had seen.

"I don't mean to be bashful," Mays said, "but I was."

In February 2010, when Mays sat with Bob Costas for a rare interview on the MLB Network, the former New York and San Francisco Giant, without arrogance, was rightly matter-of-fact about who he was and where he fit into baseball history.

"My sense of him on air — and also in private conversations — he never felt like he had to make a case for himself," Costas said in a phone interview with The Salt Lake Tribune. "What he had done spoke for itself. If you said, 'I saw you do things people didn't do in different eras,' he'd say, 'Yeah, I did that.' "

The home run was the first of 660, as he helped the Giants rally from 13 ½ games back to catch the Brooklyn Dodgers. Mays was on deck when Bobby Thompson's home run — "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" — beat the Dodgers for the NL pennant.

Mays was a five-tool player. He also had charisma, as explained by the late Leo Durocher: "[Mays] had that other ingredient that turns a superstar into a super-superstar. He lit up the room when he came in. He was a joy to be around."

Ted Williams simply said: "They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays."

Dan Franks, son of late San Francisco Giants manager Herman Franks, spent summers hanging out in the team's clubhouse, shagging fly balls and enjoying a front-row seat to the daily spectacle that was Willie Mays.

"His routine stuff was pretty spectacular," Franks said.

In 1948, there were 400,000 television sets in America. By 1950, 10 million sets were tuned into baseball, and New York City was the hub of American media. It was a perfect storm made for the outgoing, charismatic "Say Hey Kid."

Former Utah Jazz President and coach Frank Layden was a Brooklyn teenager and huge Dodgers fan. Back then, fans would argue about who was the best center fielder: Mays, New York Yankee Mickey Mantle or Brooklyn's Duke Snider.

Snider, it would turn out, wasn't in the others' class, while Mantle was slowed by injury.

"Mays was such an exciting player," Layden remembered. "Great base runner, great fielder. It was an exciting time to grow up in New York."

Mays, nicknamed The Say Hey Kid because he had trouble remembering names as a young pro and used the all-purpose moniker "say hey" when trying to get the attention of others, remains an icon.

"Some of the [older] guys have fallen through the cracks a little bit," Costas said. "He isn't one of them."

Mays' base running was legendary. Costas related a story about one-time St. Louis Cardinals manager Johnny Keane warning his outfielders to never try to throw Mays out at the plate when the game was in the ninth inning or extra innings with other runners on base.

"[Cardinals catcher] Tim McCarver told me … Mays would try and make it look closer than it was."

This tactic allowed other runners to move up an extra base.

During his interview with Costas, Mays said, "I guess I was more of a team player than just an individual player. I liked for the team to win. … That was more fun to me than hitting four home runs and going in the clubhouse and everybody's mad because we lost the game. So a lot of things happened in baseball that I had a little bit of control over, but I would have rather been known as a complete player, a team player, not showing up anybody on the field or off the field — just, you know, a nice guy."

Then there was "The Catch" in the 1954 World Series, still seen as one of the greatest ever made — one that Mays downplayed. Mays caught the ball, his back to the infield, nearly 460 feet from home plate.

"When Vic [Wertz] hit the ball to center field, I never was worried about catching the ball — I was worried about getting the ball back into the infield [to prevent the runners on base from tagging up]," Mays told Costas.

Costas, whose closest comparison to Mays is a young Ken Griffey Jr., points out, "With all due respect to Hank Aaron," had Mays not been robbed of nearly two years by military service, it might well have been Mays, and not Aaron, to first beat Babe Ruth's record for career home runs.

It all began 60 years ago, when Mays was 0 for 5. Then again, maybe the pregame batting practice told the real story.

As the late Bill Rigney, a Giants reserve who later became the team's manager, remembered:

"He popped it up, hit a weak grounder, fouled one back," Rigney writes in his book When We Played the Game. "Then all of a sudden, he hit a rocket that landed in the middle of the upper deck in left field. Then he hit another rocket that went over the roof. Then he hit one that hit the … scoreboard [in right center].

"Everything stopped. The Phillies stopped warming up, and [Richie] Ashburn and 'Puddin' Head' Jones and all the others stopped to watch him hit. He got everyone's attention. He was amazing."

The amazing Willie Mays.

Twitter: @tribmarty —

'Say Hey Kid' one of the all-time greats

When his career was done, Willie Mays would be named NL Rookie of the Year, own two MVP awards and tie a record with 24 All-Star Game appearances. He would also be one of four NL players with eight consecutive 100-RBI seasons. Second on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and a member of the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, Mays led the NL in home runs four times. He also led the league four times in stolen bases. Mays won 12 Gold Gloves, finished in the top five of MVP voting nine times and had a .302 career batting average.

• See videos of Mays interviews on our website. > sltrib.com —

Video interviews with Willie Mays

Mays on his early career • atmlb.com/jU8FYM

Mays on the best player ever • atmlb.com/jiaFGK

Mays on Bobby Thomson's home run (excerpt) • atmlb.com/mvJPvU

Hank Aaron on Willie Mays • atmlb.com/izbxZ3