This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

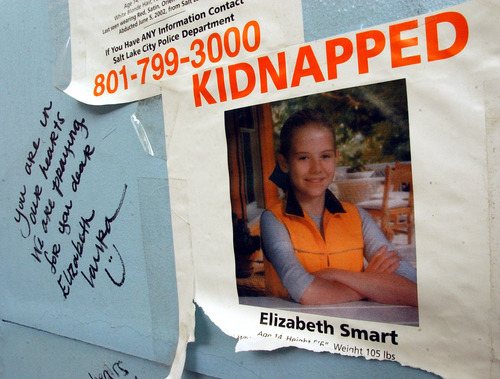

When Elizabeth Smart takes center stage in a federal courtroom this week, the nation will watch as she confronts for one last time the man convicted of her kidnapping and rape. Smart is still contemplating the words she will use to describe the impact Brian David Mitchell had on her life when he snatched her from her bedroom in 2002 when she was 14.

Yet she is unwavering in her plan to use the courtroom finale, which coincides with National Missing Children's Day, to spread hope to other victims as an advocate.

Once Wednesday's sentencing concludes an eight-year legal drama, the 23-year-old will face a choice other women who have survived high-profile crimes know well: How much of her life might be lived publicly? Will Smart take a path of active advocacy or opt for a quieter life removed from rehashing the story that labeled her to many as simply "Elizabeth Smart, kidnapping survivor"?

The answer isn't clear.

"Right now, I'm just sort of staying open and not closing any doors yet," a cautious Smart said Thursday of her future. "I want to go where I can do the most good and make the biggest difference. Time will tell."

—

The road from victim to advocate • Yvette Rodier can relate to the choice ahead of Smart.

She was a week away from starting college at the University of Utah in 1996 when she became front-page news. A gunman randomly shot her and friend Zach Snarr as the two photographed the full moon over Little Dell Reservoir on a first date.

The two 18-year-olds were setting up cameras when a man approached to ask for directions. They didn't have an answer for him, and when they resumed their photography, he pulled out a gun and opened fire. Snarr was shot three times and died instantly. Rodier, wounded in the leg and torso, screamed in pain as the shooter calmly reloaded before firing another shot into her head.

Rodier played dead as the man rifled through her pockets, and then Snarr's clothing, before he grabbed keys and drove away in the Ford Bronco that Rodier and Snarr arrived in. Rodier screamed Snarr's name after the shooter left. He didn't respond.

Alone in the canyon, Rodier crawled up a steep, rocky embankment for help. Blood streamed down her face and smoke from the gunshots filled her lungs. After a 30-minute trek to the road, she flagged down a passing motorist.

Rodier lived but quickly realized life would never be the same.

Later, Rodier would learn Jorge Martin Benvenuto had shot her and killed Snarr because he wanted to see what it was like to shoot someone and watch them die. The case of the "thrill killer" captured headlines as his murder case moved through the court system.

Rodier agreed to speak publicly about the shooting when asked, appearing at conferences or meetings about crime victims soon after it happened. But privately, she wanted to hide.

"I didn't want to be the girl who got shot," she said.

She started college as planned two weeks after the shooting. But other students quickly recognized her, particularly when she missed school or wore bandages as she recovered from five operations for her head wound. She retreated inward, self-conscious of the attention, she said.

"I was terrified to be out in public," said Rodier, now 32. "I realized if I stopped making eye contact with people, they wouldn't talk to me."

Just when she thought her identity as a crime victim had started to fade, a resurgence would occur when Rodier testified in court, her face again flashed all over the news.

She found a close group of college friends who supported her as court proceedings continued — a process that lasted through all four years of school. The longest healing process for Rodier has been mending her psychological scars.

Initially, she couldn't sleep and would wake up from horrible nightmares about loved ones dying. Even now, Rodier said she's still haunted by memories of Aug. 28, 1996. She's riddled with guilt for leaving Snarr on the ground, even though she left in a desperate attempt to find help.

"I left him. I didn't stay right there with him. I didn't sit with him and hold his hand," she said.

She never thought the crime would steer her away from her intended career path as a broadcast journalist, but that changed gradually as she worked at a law firm to pay for college.

Rodier ended up working for former U.S. District Judge Paul G. Cassell, where she developed a fascination with the legal process and its impact on crime victims. She observed attorneys who were effective at securing justice for their clients and others who botched cases.

Deciding she wanted to practice law, Rodier enrolled in law school at the University of Utah. She graduated in 2008 and is now an attorney for the grant-funded Utah Crime Victims Legal Clinic.

In her role there she helps clients navigate the court system and speaks on their behalf in a range of settings from courtrooms to parole hearings.

Some of Rodier's clients learn about her own past as a victim; others don't know her history. She said her personal experiences have helped her connect with victims faster.

"It's this unspoken feeling. There is a connection," she said. "There's just that extra second hug. You just know you understand each other."

Rodier in recent years has traveled across the country and spoken at conferences for victim advocates and attorneys. For her, sharing her personal story is therapeutic and empowering, instead of burdensome baggage she once preferred to hide.

Rodier remains close friends with Snarr's family. She married and has a child. Each August, she allows herself a day to grieve and relive feelings of anguish, terror and guilt on the anniversary of Snarr's death. Knowing an emotional release will come on that day allows her from falling into a trap of living in the past.

Even though 15 years have passed, there are the moments when memories of the shooting come flooding back. She reminds herself to take a step back and care for her own emotional needs so she can better serve the needs of her clients.

"There are times when I hang up my phone and cry. It's a constant process," she said. "I have moments when it feels too hard."

The satisfaction she gains from making a difference in her clients' lives keeps her going.

"The textbook line that helps is that the crime does not define you," said Rodier. "If there are choices you can make that makes the crime a positive part of your life, reach for those."

—

Finishing what she started or starting anew? • No matter what Smart chooses to do in the future, she has already built a résumé when it comes to victim advocacy.

In March, she earned an award from The Diller-von Furstenberg Family Foundation that came with a $50,000 check she will use to start The Elizabeth Smart Foundation, aimed at protecting children from abuse. The foundation will focus on prevention, education and promoting radKIDS [Resisting Aggression Defensively] — a program teaching children about calling 911 and making defensive moves against attackers.

Smart has said she wants to see radKIDS implemented in every elementary school but hasn't yet specified what her personal position in the foundation will be. She is also toying with the idea of law school.

Her foundation complements other efforts by Smart and her parents, who in 2006 made an appearance to Congress to lobby for a new law creating a national sex offender registry. She was on hand when President George W. Bush signed into law the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act.

Smart in 2008 also shared her story in a booklet titled You're Not Alone, which is published by the U.S. Department of Justice and given to survivors of abduction. She wrote in one passage, "I made a conscious decision that my abductors had already taken away nine months of my life, and I certainly was not going to give them any more time than that."

After Mitchell's Dec. 10 conviction for her kidnap and rape, she boldly stood on the courthouse steps claiming her victory in court on behalf of all victims of sexual violence and abuse.

"I am so thrilled to stand before the people of America today and give hope to other victims who have not spoken out about what's happened to them," she said. Smart said her experience shows "it is possible to move on after something terrible has happened, and that we can speak out and we will be heard."

Her grace and composure drew praise from many, including social workers, victim advocates and others experienced in working with rape victims in Utah.

"There is such shame associated with sexual violence, and to have it being talked about is almost a relief to some," said Heather Stringfellow, executive director of the Rape Recovery Center in Salt Lake City, during an interview shortly after Mitchell's conviction. "She held Mitchell accountable, and that's a very powerful message."

—

Making the choice • Speaking about rape was initially too difficult for Brandy Farmer, a survivor of rape and domestic violence who kept her story secret for years before sharing it. Farmer says she felt ashamed.

Farmer, a Salt Lake County resident, was sexually assaulted as a 14-year-old by her boyfriend's older brother. She never reported the crime. In her 20s, she was gang-raped by a group of men who took her by force from a fairground in California, where she had gone to meet her husband, a traveling salesman who was working at the fair.

The men drove her to a home in Los Angeles and took turns raping her, she said.

"I just closed my eyes and thought, 'Maybe they won't kill me,' " she said. After several hours, the men dumped her back at the fairgrounds. Terrified her husband would blame her for the assault, she didn't tell him what had happened.

It wasn't until years after Farmer left her physically controlling and abusive husband in 1982 that she decided to tell her story. She had decided to become an advocate and found she wanted to share the unspeakable details of her rapes with others. She came to realize the unhealthiness of bottling up the story of violence she'd survived.

"I felt like I was in a tunnel and watching a movie about myself outside of myself," said Farmer. "I remember thinking I was in a big room and there was a tiny window on top. I thought, 'Someday, I'm going to be on the other side of the window.' "

Over time, Farmer gained confidence and found a stronger voice that led her to become chairwoman of the Utah Domestic Violence Council.

For years, she has been a staple at Capitol Hill, where she pushes for funding and better education connected to domestic-violence prevention. She started a dating-violence awareness campaign in Utah and is known for her volunteer work in several spheres, including the Latin American Chamber of Commerce.

Decades after her own rapes, Farmer's motivation is rekindled when she hears about another victim. She believes there is hope that people can change, that those inclined to react violently can learn to see that there is a better life ahead.

"I don't look at what happened to me as baggage. It was almost as if I experienced it so I could help other people," Farmer said. "Who do we learn from? We learn from survivors."

Farmer's recommendation to Elizabeth Smart is to take the direction that feels right as she decides which road to take into adulthood.

"Follow your heart," she said. "Because your heart will lead you."

Twitter: mrogers_trib