This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In 1941, Robert D. Shaffer was a Marine second lieutenant aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet in Norfolk, Va., when he got a copy of a dispatch that read in part, "Execute War Plan 46 against Japan."

It was Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, and the beginning of a world war that would last four years and take millions of lives. It was also the beginning of a military career that would take Shaffer to the Battle of Midway, throughout the Pacific Theater and on to the war crime trials in Tokyo.

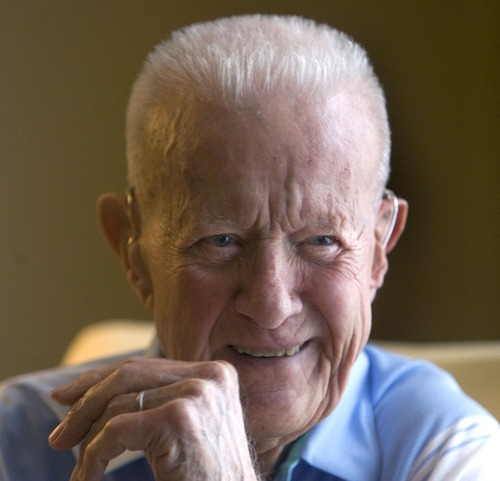

I met with Shaffer at his home in Salt Lake City last October. A retired lieutenant colonel, he greeted me graciously and led me to the living room, a near-museum with artifacts, mementos and a couch draped with a big fleece blanket bearing the Marine Corps emblem.

A long-time gunnery officer, he wears a pair of hearing aids. He's tall, with a now-white flattop and a sonorous voice. He remembers everything.

Shaffer launched his military career in the Army ROTC at the University of Illinois, where he graduated in journalism and liberal arts in 1940. He'd chosen the Marine Corps, though, not least because at the time, he was in a cavalry training unit with World War I equipment.

"Listening to midshipmen — the places they'd gone — service afloat sounded good," Shaffer said. "I was assigned to the Hornet. I'd never been on anything but a rowboat, and the flight deck was 800 feet long."

At the time, there were only about 20,000 officers and enlisted men in the Corps, and Shaffer spent his first few months as a recruiter in Illinois, wearing a tailored uniform he had to pay for himself.

In 1942, he commanded a gunnery crew aboard the Hornet. That spring, the Japanese Navy was trying to lure the U.S. fleet to Midway, an atoll about halfway between Hawaii and Japan, to finish the job they'd started at Pearl Harbor.

But Admiral Chester Nimitz's team of cryptoanalysts broke Japan's naval code, which offered an outline of the plan of attack, and a counter-offense was launched.

The Hornet and the USS Enterprise were en route to Midway, as was the carrier Yorktown, which had been badly damaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea and repaired with astonishing swiftness.

About halfway to Midway, the sailors and Marines were told what was coming, and there was "a great cheer from every crew member," Shaffer said.

As they neared Midway, search planes spotted Japanese ships, and the Battle of Midway began on June 4, 1942.

The carrier's torpedo planes were led by Lt. Cmdr. John C. Waldron, who "was not too popular with pilots. He had them out on the deck running in place and touching their toes," Shaffer said. "All the other pilots sat in the ready room and drank soft drinks and looked at raunchy magazines."

When the time came, the Hornet launched fighter planes first, then scout bombers and the planes carrying torpedos so heavy they could barely clear the flight deck. Every one of the torpedo planes, including Waldron's, was shot down and their crews killed. The only survivor was Ensign George C. Gay, who went into the water and hid under an aircraft cushion until he was picked up by a destroyer.

In the thick of battle, the Japanese fliers followed the Yorktown's planes and "bombed the hell out" of the carrier, Shaffer said. Unable to land there, some pilots were directed to the Hornet.

Which is where Shaffer came as close as he ever would to being killed in battle.

As one of the fighters landed, his right undercarriage collapsed and his forward machine guns went off.

"Lt. Ingersoll was standing right next to me," Shaffer said, his hand just inches from his side. "He was hit in the heart. A machine gun crew was on the flight deck, and they all were killed."

The pilot survived.

"I never found out if the pilot was wounded or made a mistake," Shaffer said. "They got him off the ship."

That first day, the Americans sank the Akagi, Kaga and Soryu. Early the next morning, they sank the Hiryu — completing the annihilation of the four carriers that destroyed most of the U.S. ships at Pearl Harbor. In all, five Japanese ships were sunk, 228 aircraft shot down and 3,057 men killed. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's plan to destroy the U.S. fleet in the Pacific had failed.

The U.S. lost the Yorktown and the destroyer Hamman, 145 aircraft and 340 men.

That August, U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal, beginning what's known as the long march to Tokyo. For Shaffer and so many others, the war would last for three more years.

Peg McEntee is a news columnist. Reach her at pegmcentee@sltrib.com. —

The Battle of Midway

Retired Marine Lt. Col. Robert D. Shaffer of Salt Lake City survived the 1942 Battle of Midway, a turning point in the War in the Pacific. His story continues on Sunday, June 5.