This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When Josh Stout tries to explain it to his friends, it's hard to understand.

Yes, he plays on Utah's lacrosse team. No, it's not actually an NCAA-sanctioned sport, and it doesn't fall under the university's athletic department. Yes, they play other teams from other states. No, they're not on scholarship.

But Utah lacrosse is better understood once it is seen in person. The team practices on the track and in the indoor football facility. They lift in the same weight rooms as the Division I teams on campus. Their coach was an assistant for the Division I national champion last year, and he fields a staff of Major League Lacrosse veterans.

They sell tickets to games — actual tickets with printed team logos — and they hire referees, stream their games online and send press releases of their results. At a recent game, a public address announcer rumbled, "Get ready for the fastest game on two feet!" as Utah lined up in matching uniforms to play under the lights on Utah's soccer field, with a staff of security and maintenance workers on hand.

"Not a lot of people understand, 'Yeah, we're trying to go DI,'" says Stout, a freshman in the program. "But we look the part."

It's a more elegant version of "fake it til you make it" — Utah lacrosse looks, for all appearances, like a Division I team. Quietly, they've assembled the financial backing and following of a Division I team. And perhaps as soon as two years from now, that's what they could be.

What's going on here?

Utah's club lacrosse team has been around for a while. But it has only been kicked into overdrive in the last year, when the program got the attention of David Neeleman.

If the name sounds familiar, consider that Neeleman has helped found four airlines, most notably JetBlue. He took his latest airline, a Brazilian company named Azul, public two weeks ago. A millionaire who mostly lives in Connecticut, he got caught up in another passion closer to the ground: lacrosse.

His sons played the sport, which has a sizeable following on the East Coast. When his son Seth Neeleman, a strapping 6-foot-4 defenseman, was reconsidering attending Loyola University in Maryland on a lacrosse scholarship as he was preparing to return from an LDS Church mission last year, David started hunting for other options where Seth could pursue both sport and spirituality.

He settled on Utah, the college where he had dropped out as an undergrad, but a school still dear to his heart. It had a struggling program run by Rick Kladis, who wanted to remain involved, but was looking for someone else to take on coaching duties.

An entrepreneur at heart, Neeleman saw an opportunity — for lacrosse and for the university.

"I saw a way to put Utah on the map in lacrosse," he said. "The sport is growing, and I talked to people who think the balance will shift West."

Sometimes, the best way to shift the balance is to shift it yourself. Kladis told Neeleman that he'd be ready to step aside if he could find a coach who could steer the Utes upward toward NCAA sanctioned status. Neeleman got a list of potential candidates from lacrosse contacts back east, then did the only thing he could think to do.

The coach

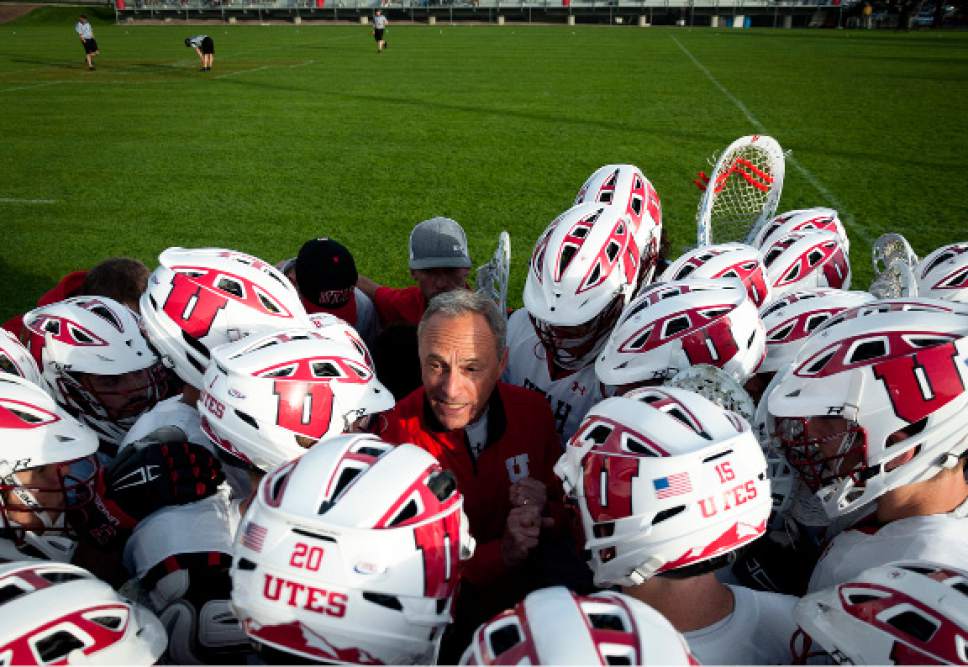

In the midst of what would be a national championship season for North Carolina, assistant coach Brian Holman found himself at a crossroads.

Holman, 56, was considering Chapel Hill for the rest of his career, the school where his children played lacrosse and where he had mentored players for years. But he also had a desire to run his own program, and one of the people who pushed him to look for a head coaching job was his boss at UNC, Joe Breschi.

"I always said, 'You've got to follow your dreams, because life is too short,'" Breschi recalled. "Coach Holman is such a good person and a great communicator. I think he wanted more to touch kids' lives."

He put out feelers through colleagues: Which jobs would be open? Where did he have a chance? One of those options was at Utah — a school with no significant lacrosse tradition to speak of, a struggling club team, and a would-be donor with some crazy ideas.

It's hard to overstate what a leap it appeared to be. Denver is currently home to the westernmost DI men's lacrosse program, and only two Power 5 schools have added lacrosse within the past 30 years. Lacrosse isn't a high school sanctioned sport in Utah.

As Holman, a slim man with a Clint Eastwood-like jaw, remembers his first conversations with David Neeleman, he does what he did then: laughs.

"I said, 'No way,'" Holman said. "I literally laughed over the phone. I told him, 'I don't see this working.' I didn't want to waste his time or mine."

But at the urging of his family, particularly his wife, Holman was swayed into flying out for a weekend staying with Neeleman in Deer Valley and getting to know the University of Utah. Suddenly, many of the wilder aspects of Neeleman's vision seemed more realistic. He got an eyeful of the mountain scenery, the academic profile of the school, the success of the sports programs there.

Holman found himself asking: Why couldn't this work?

"I just felt a solid connection there," he said. "It just stirred my innards. I told my family, 'Hey, it's going to be like the Wild, Wild West out there.' And my wife said, 'Well, you're kind of a maverick anyway. Maybe it's a fit.'"

The team

When Stout made the decision to forgo his chance to play for Westminster and go to Utah instead, he had been told by Holman that it would be tough.

"I didn't expect it to be easy," Stout said, "but I wasn't expecting it to be as hard as it was."

With a roster of roughly 50 players at the start, none of whom was recruited by Holman, the rebuilt Utah lacrosse program went to work. With funding provided primarily by Neeleman, the team worked out on Utah's fields and in the athletic weight rooms up to nine times per week. They had practices, team lifts and a constant grind of activities. Even though they had no scholarships, coaches still checked grades to make sure they were keeping up academically.

Today, the roster lists 31 players — the 31 who could keep up with one of the most demanding club programs on campus.

"It's physically demanding and consumes a lot of your time, but it's also mentally draining," Seth Neeleman said. "But we're not here to be a mediocre team. We're not here to give 50 percent. … That's what makes us better. Some people think that's not necessary, but we're going at it every day."

Holman has a staff that is well acquainted with the demands of high-level lacrosse: Three of them, Adam Ghitelman, Marcus Holman (Brian's son) and Will Manny play for MLL teams, and the entire staff played college lacrosse. The coaching staff can easily step in during any practice and give players a taste of what elite competition is like.

But it's not just the level of coaching or commitment — many other aspects of the program have a professional polish. That was most apparent to Stout on Utah's first road trip to Chapman, the defending Men's Collegiate Lacrosse Association champion. The trip had a structured itinerary, meals were provided and the rigidity of the schedule allowed Utah's players to focus entirely on the game — "Having all that organized really put me at ease," Stout said.

They won, 12-9.

"Attention to detail is paramount," Holman said. "We want to be the best-run club program in the country. We think we have something that kids will want to be a part of, with coaching that is some of the best at this level."

Something is working: Utah is 10-5 this season, the program's best record in years. They've won big games against Colorado and Colorado State, clinching the No. 1 seed in the Rocky Mountain Lacrosse Conference and setting themselves up for a national postseason berth.

Is it a flash in the pan? Utah's recruiting class makes that seem unlikely — yes, an actual "recruiting" class, made up of players from 16 different states who agreed to come to Utah with no promise of a scholarship, but the hope that they could be a part of something special.

The Utes believe they'll continue to get players from the West who will give them a look, but also Eastern players who want a change and would enjoy the trappings of a big state school. The 2017 class is made up of players such as Reid Lanigan from Memphis, Tenn., who had Division III offers and some light Division I interest. But when he came to Utah on a visit for the first time, he was floored by what he saw.

"I've lived in Memphis my whole life, so the scenery was really cool for me first off," he said. "But I think the other thing is that lacrosse is looking to become DI. That's why it's amping up the way they recruit — the idea of being part of a new program. When we graduate college, we'll look back and think that's something that we started. Something new. Something special."

The future

Behind the fresh-faced optimism that has come with all the changes and winning games is a quiet uncertainty: What happens if lacrosse doesn't go DI at Utah?

Behind the scenes, there's much in the works: Athletic director Chris Hill said a university committee is looking at adding it to the department, and David Neeleman and Brian Holman have met with the administration several times. At the last Utah home game, a loss to Texas, associate athletic director Manny Hendrix watched the game alongside Neeleman, mentioning that he was impressed by the crowd of several hundred fans in the soccer stands.

There are a lot of factors to consider, but many of them break in lacrosse's favor: The sport has only 12.6 scholarships, which wouldn't necessarily cause a Title IX issue on Utah's male-majority campus. Academically, Holman touts the 3.6 GPA of his team, with a 26 average ACT score for his incoming recruiting class. The team has also taken time to volunteer at local hospitals, and Holman says he sees community service as a core tenet of his program in the future.

Neeleman envisions lacrosse as a revenue sport. While he acknowledges his checkbook has enabled the hiring of Holman, the use of Utah facilities and eased strains on the travel budget, he points to the team's "Founder's Club" of more than 100 boosters. The team also sold roughly 1,000 season tickets between $59 and $99 per head. Neeleman has talked to Pac-12 commissioner Larry Scott about lacrosse and its potential as a televised event.

"It's not about me or my kid — it's bigger than that," Neeleman said. "I really dream of a time when I can walk into a conference room in New York, and half the businessmen in the room will be talking about Utah's lacrosse game over the weekend. It's really a huge opportunity for the sport and the university."

Hill is more circumspect. He stresses that his budget, the 11th-largest in the Pac-12, is still strained. Adding lacrosse is likely at least a million-dollar cost, and he wants to be assured that it has a steady financial future before it gets approved to join the Division I ranks.

"The club is taking a lot of initiative to make it a better and more visible club sport," he said. "It's a good thing that people are so interested. But I'm more worried if it's the right thing to do and if we can afford it. The last thing we want to do is put a drain on the other sports we have here."

That decision could be soon; Holman hopes the program could go Division I as soon as the 2019 season. It would make Utah the first Pac-12 school to add men's lacrosse, and potentially put it on the path to being a Western powerhouse.

If anyone can spark a Western revolution, Breschi said, he thinks it's Holman.

"I would love to see the Oregon and UCLAs and USCs all go DI in men's lacrosse," he said. "It would be fantastic. I think we all see it happening slowly. … There could be a lot of opportunities for coaches to build your own program. I think we would see a lot of guys move out that way."

But then there's that question: What if it doesn't happen?

From Holman, his staff, his players and his recruits, there is a singular answer: If Utah lacrosse doesn't go Division I, they'll keep trying to bust the doors off their club competition.

"Worse things could happen," Holman said. "I've come out West, I've become a better person, a better coach. I've learned things that I would've never learned if I had stayed at UNC. I'm really so proud of these guys — they've been kind of like the Bad News Bears and come together to have a great season."

For a player like Stout, not going DI is more of a detail than a make-or-break factor. He hopes it happens — they all do. The team has worked hard to look like a Division I team.

But in the end, in coming to Utah, he's gotten what he was looking for.

"It's always been kind of a dream of mine to play for a Division I school," he said. "But going DI is so insignificant to playing under such a great staff for four years. If that's how it happens, I'll be OK with it."

Twitter: @kylegoon —

Why it will work

• The Utes have a coaching staff in place and immediate financial backing, with only 12.6 scholarships added.

Why it won't work

• The athletic department might not have confidence in the long-term financial plan or will decide to concentrate on current sports.