This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

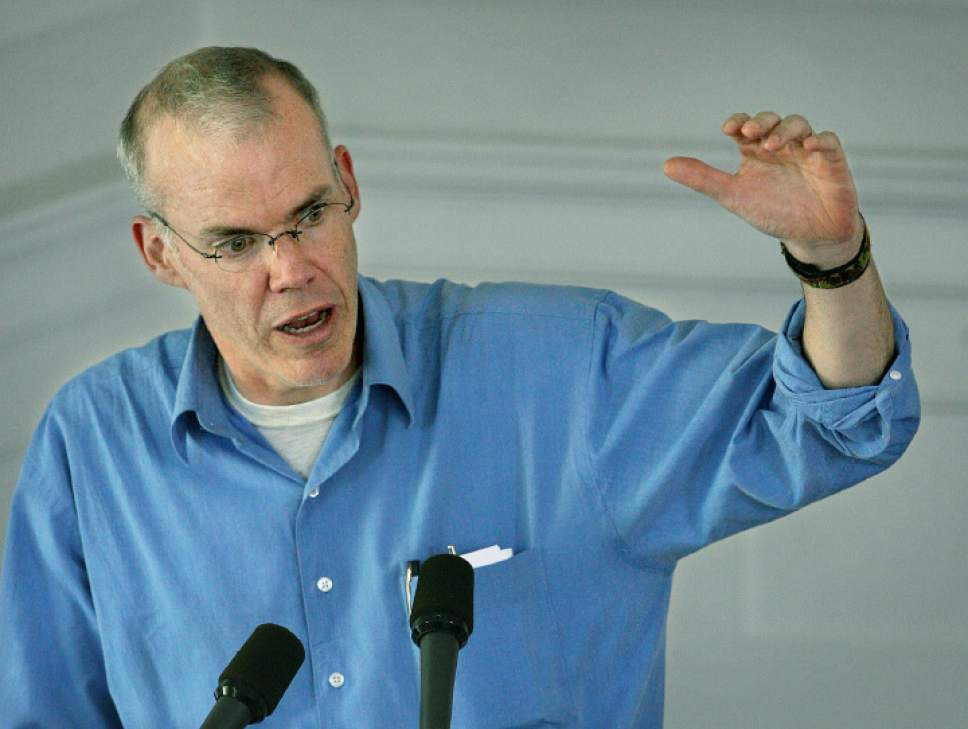

Washington • Bill McKibben, whom some call the world's most famous environmentalist, headlines the People's Climate March on Saturday at the National Mall, where he will forcefully make the case — as he has been doing for decades — that the Earth hangs in the balance.

On the stump with former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, or writing the lead piece in The New York Times' Opinion section, McKibben talks tough: "the planet can't stand this presidency" and the GOP, as he told The Washington Post recently, "is a wholly owned subsidiary of the fossil fuel industry."

But even fans of McKibben may not know that the founder of the 350.org environmental nonprofit is also a religious man — a churchgoing former Sunday school teacher who has written passionately and extensively about the spiritual underpinnings of his drive to save the planet.

Religion News Service spoke to McKibbon as he rode a train to D.C. for the march. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q • What's your faith history? How were you raised?

A • I've been a good mainline Protestant of many flavors over the years. I was born in California and baptized as a Presbyterian. Then we lived in Toronto for five years, so I started Sunday school at the United Church of Canada. And then we moved to the suburbs of Boston, where the local flavor was Congregationalist and I belonged to a high school youth group in the United Church of Christ. And then I moved up to the mountains [the Adirondacks] as a young man where the dominant flavor was Methodism. So now I'm a Methodist.

Q • What's it like to teach Sunday school?

A • I quite enjoyed it in my 30s and 40s, in churches on one side or the other of Lake Champlain. Not that I was very good at it. In my Sunday school class, we tended to do a lot of hiking. I'm not sure my class wound up with much dogmatic understanding of the church. But we always celebrated St. Francis Day. We'd bring in everybody's pets to get blessed, but also I would make sure that the children brought in representative fauna from the forest — mosquitoes and snakes, too — just to make the point that it's all creation and it's all blessed.

Q • Many people think scientists and environmentalists can't be religious, or that their spirituality is limited to walks in the woods. Why do people draw a line between faith and science?

A • I don't know. Clearly there are plenty of scientists who are skeptical about theology of various kinds. But that doesn't bother me particularly. It doesn't bother me very much when anyone is skeptical. I'm always more bothered by people who insist they are faithful, but it would be hard to tell by the way they treat the world around them.

Q • Why did you write a whole book that riffs on the Book of Job ("The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job, and the Scale of Creation")?

A • I've always loved Job. Luckily my wife, who is Jewish, for some reason in our 20s handed me a copy of Stephen Mitchell's wonderful translation of the Book of Job, which renders a difficult-to-read book into something gripping and quite amazing. That soliloquy that God delivers at the end of Job 38 and what follows is, I think, the longest speech that God gives anywhere in the Bible, Old Testament or New, and the first piece of nature writing in the Western canon.

It's incredibly biologically accurate, sexy and crunchy. It's a sarcastic speech that God gives, taunting Job: "If you're so smart, can you tell me where I keep the wind and the snow? Can you whistle up a storm? Can you tell the waves where to break?" For Job, like for all people, all he could say was "No, you're in charge. Can I sit down now?"

My realization was that for us now, that's changed. We are large enough now to spit in God's face — and we are. Now it's us who have to decide how high the waves go, how many storms we are going to get and how strong they're going to be.

Q • Though your Sunday school teaching days are over, why did you decide to teach the Bible to college students?

A • Two years ago at Middlebury College where I teach (environmental studies), I taught a course called "Stories From the Bible." We have wonderful and very smart kids at Middlebury. It's one of the best colleges in the country. They can all do calculus standing on their heads. They know Arabic backwards. But very, very few of them had even a rudimentary understanding of any of the stories from the Bible.

We had a great time and worked through only a little bit of the Old Testament. The stories are one after another wonderful. We did Tower of Babel one week and move on to wrestle with angels. And it reinforced my sense that Job was in a sense the first really modern story. It didn't come with an easy moral about sin. It's one of the reasons why it's always been difficult, but useful for our moment.

Q • When you speak at climate marches or political rallies we don't hear this Bible talk much. Since some of those best-versed in the Bible are among those most skeptical of climate change, why not talk this way more often?

A • I do when it's with people who can hear it. I like talking to these audiences. Not long ago I went to New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary for several lectures. I enjoyed it and it went well. I try to do that sort of thing when I can. But for many Americans, even those who spend time in church, it's not always that useful to be referencing Job. Even a fair number of American Christians probably aren't all that well versed in the Bible.

Q • Do you think if we were more biblically literate as a society we would be better caretakers of the planet?

A • Maybe, but I don't know. I haven't noticed any great correlation. I'm afraid if you look around, it's often people who are least likely to be engaged with the church or a synagogue or a mosque who are often standing up for creation. And a lot of people have tried to use the Bible to figure out rationalization for doing what we're doing to heat up the planet, kill of species and whatever else.

Q • You have occasionally been likened to a prophet, the bearer of a message about the fate of the Earth. Do you think of yourself as one in any way?

A • I am not a prophet. I have never vouchsafed any particular message from the Lord. I do my best to read the signs of the times, and in our day and age it often means listening hard to what scientists have to tell us.

Q • Do you have any particular message for people of faith who want to do something about climate change?

A • We're in a very dire situation with climate change. It's not clear whether we are going to be able to significantly slow it down. The best science indicates that we have a narrow window to do that if we act with great speed. Even that is not certain. It's a bad sign that we've melted most of the Arctic.

The one advantage that people of faith may have is that they're able to at least hope that if we do everything that we possibly can, the world may meet us halfway. As long as faith leads one deeply into action, and not deeply into inaction, then that's a very good thing.