This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Highland • Nerves of steel and a big, warm heart.

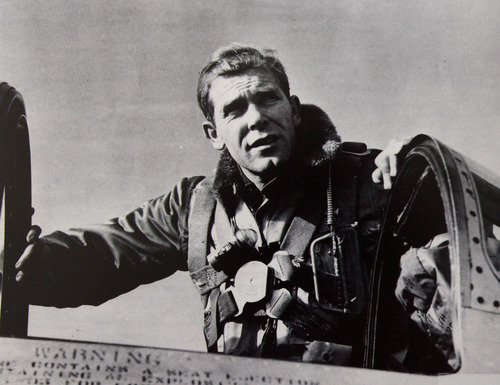

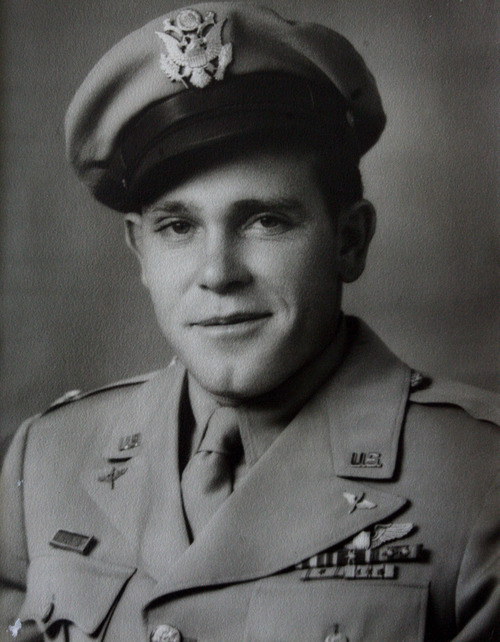

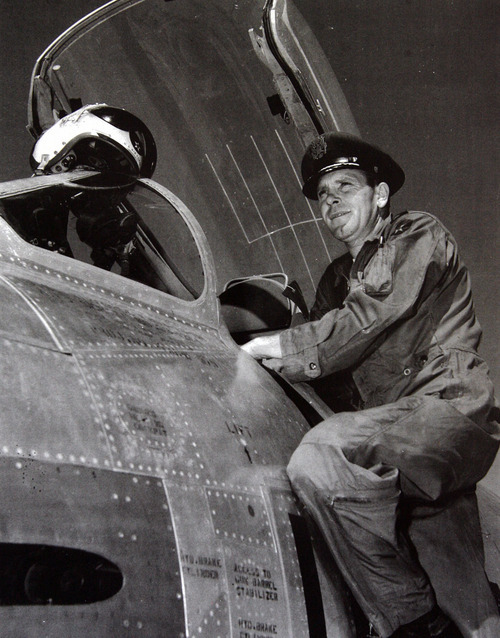

Both describe Emmett "Cyclone" Davis, a highly decorated fighter pilot who saw historic action in World War II — from the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor to his last mission four days after the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

At 92, he remembers the Japanese surrender, VJ Day, on Aug. 14, 1945, like it was yesterday.

"It was just a relief to know we were victorious in the war," he recalled last week at his comfortable home in northern Utah County.

And with a sparkle in his eye, he remembers how after the war, he bought his sweetheart, Marge, a new Buick. He kept the title long enough to drive her up a canyon east of Salt Lake City to recite a love poem in which he asked her to marry him. He can still recite it, word for word.

"She said, 'Well, maybe,' " he recalled, shooting Marge, now 90, a grin.

They were married Jan. 23, 1946, and have three children.

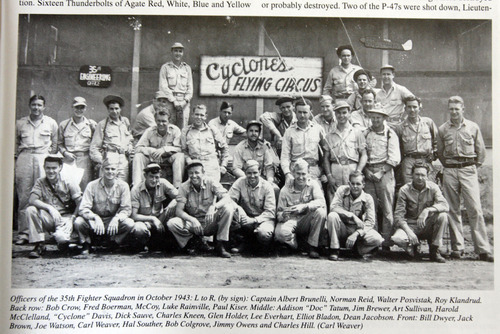

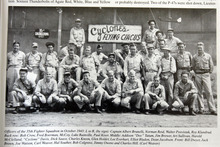

He got the handle "Cyclone" from the dogfight, spiral maneuver he invented to flummox his airborne adversaries. The name stuck. And he was so popular with his men that the squadron and, later, the 8th Fighter Group that he led took the moniker Cyclone's Flying Circus, said his son J. Tucker Davis.

Cyclone was born on Dec. 12, 1918, in Roosevelt. His family eventually moved to Salt Lake City, where he graduated from East High School. After a year at the University of Utah, he joined the Army Air Corps.

He chose the Army, he said, "because they were the first to accept me."

After basic training and flight school, he volunteered for Hawaii, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt had transferred the Pacific fleet.

Davis was assigned to accompany the USS Enterprise to the islands with a cargo of P-36 fighters. With only about 20 hours of flight time under his belt, he was frightened — one of the only times during his service — when ordered to take off from the ship's deck.

"The flag man would wave you on when the bow of the ship dipped. I took off, it seemed, right into the water. It was frightening."

—

Infamous day •On Saturday night, Dec. 6, 1941, Cyclone and his colleagues had gone to a dance and stayed up late partying. Then a lieutenant, Davis was six days shy of his 23rd birthday.

"I went to bed at 2 a.m. and about dawn my roommate shook me and said, 'Cyclone, wake up, the Japanese are here.' "

The pair jumped into a convertible and raced toward the airfield. On the way, they were strafed by Japanese warplanes, Davis recalled. Once there, they began moving U.S. fighters, lined up wingtip to wingtip, out of the flight line to keep them from burning in a spreading fire.

At one point a Japanese fighter came in so low that Davis could see the tail gunner sighting in on him. He was sure he would be killed, but the plane didn't fire.

"I could see him smiling," Davis said of the gunner. "I'm still not sure why he didn't shoot. Maybe he was out of ammo."

Eventually, Cyclone got airborne in a P-40 fighter. He was one of only a few American pilots to do so that day.

His son Tucker, who is writing a book on his father's service, said that many believed the Japanese were invading Hawaii. Cyclone pointed his plane toward Barbers Point to meet the invasion, thinking he might be the only U.S. plane in the air.

During the confusion, Cyclone came under fire from U.S. Navy forces, who were shooting at anything in the sky. "I radioed in and told them to get the Navy under control," Cyclone said.

When the day was done, the Japanese had sunk or badly damaged 18 U.S. ships, including four battleships sunk and four severely damaged. U.S. aircraft destroyed numbered 188. And 2,404 servicemen were killed, with 1,282 wounded.

"But luckily, our aircraft carriers were out at sea," Davis said. "And that gave us a foothold for the war."

—

Deadly dogfight • Of the more than 250 missions he flew, one over the Island of New Britain on Dec. 26, 1943, stands out, Davis said. It was called the Battle of Cape Gloucester, where the allies were attempting to take a Japanese airbase. By then, some in Cyclone's 8th Fighter Group were flying the new P-38 fighters, the best aircraft in the sky. Davis' group was assigned to give close air support to the invading 1st Marine Division.

"That day, we were hit with 100 Japanese aircraft," Davis recalled solemnly. "The P-38s got to the Japanese first and got them out of their groove. Then we just went after them."

What ensued was perhaps the most deadly dogfighting of the war, said Tucker Davis.

"My kids got credit for shooting down 18," Cyclone said. "I shot down somewhere between two and seven."

In total, the Americans shot down 38 Japanese aircraft that day, said Tucker Davis.

For his efforts, Cyclone was awarded the Silver Star. He was 25 years old.

During his career, Davis earned 43 medals and commendations. He retired from the Air Force in 1963 as a full colonel. He spent the next 20-plus years working for Hughes Aircraft.

—

Ending the war •On Aug. 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. On Aug. 9, 1945, the U.S. dropped the second A-bomb on Nagasaki. But the Japanese did not immediately surrender, and Cyclone got orders to take his fighter group on a bombing run over the city of Kumamoto.

"The best way to attack [the city] was from the north," Davis recalled. "But I got the overwhelming sensation that was the wrong tack."

Cyclone dipped his wings back and forth, signalling the fighter group to follow him. As soon as they turned, the sky exploded with anti-aircraft fire. But the Flying Circus had escaped.

They then circled around and attacked from the south. After a successful bombing run, Davis brought all his aircraft back safely.

Four days later, the Japanese surrendered.

"It was important. I do think back on it," he said of the mission over Kumamoto. "Nothing was ever written about Kumamoto; the attention all went to the two atom bombs."

Nonetheless, Cyclone was glad to see the war end. Add lucky to the superlatives that describe him.

"I guess I felt like I was blessed that I didn't get killed in the war, 'cause I spent a lot of time at it."

Celebrating VJ Day

Three days can be considered Victory over Japan Day:

Aug. 14, 1945 • Japanese surrender.

Aug. 15, 1945 • Surrender announced to the world.

Sept. 2, 1945 • Ceremony and formal signing of surrender.